Rebecca Eissler Spring 2015 The Priorities of a President

advertisement

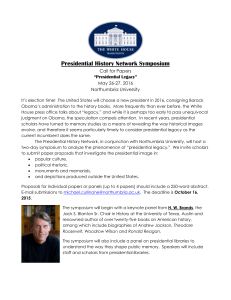

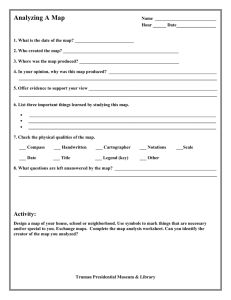

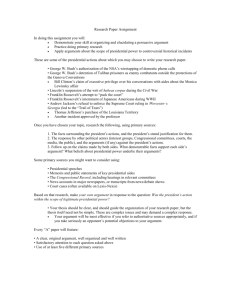

Rebecca Eissler Spring 2015 The Priorities of a President: Understanding the Presidential Agenda via Budget Messages Abstract In the United States, the president’s agenda-setting ability has long been a topic of interest. Yet most of the studies of presidential agenda-setting derive the agenda from the State of the Union Address. While it is true that a president communicates many of his policy priorities via the State of the Union, his agenda also contains policies that are not mentioned in the speech. This paper examines an additional venue for the president to communicate his agenda to others within government: the presidential Budget Message. Using the coding scheme of the Policy Agendas Project, this study of the budget messages shows that the policies discussed in the messages is substantively different from the policy mentioned in the State of the Union, largely because of the different audiences associated with the messages. Introduction In April 2001, President George W. Bush submitted his budget to Congress. As this was the first budget of his presidency, his message reflected his outlook on the budgetary process. To President Bush, “a budget is much more than a collection of numbers. A budget is a reflection of a nation’s priorities, its needs, and its promise. [A] budget offers a new vision of governing for the Nation.” The perspective that he articulated is a perspective embedded in all the presidential messages attached to the presidential budget proposals. The president’s budget is his recommendation to Congress on exactly how the money of the federal government should be prioritized: that prioritization is a key component of the larger presidential agenda. !1 Agenda setting is a highly studied aspect of the policy process literature. As early as E.E. Schattschneider, political scientists have realized the importance of understanding the policy agenda (Baumgartner 2001). Studying agenda setting allows us to understand conflict expansion (Schattschneider 1960), the definition of alternatives (Bachrach & Baratz 1962), and the way that political actors are able to shape policy change (Cohen et al. 1972; Kingdon 1995). The agenda is often defined quite simply as the list of subjects to which political actors are paying attention (Kingdon 1995). So agenda setting is the process of deciding which subjects are on the list and which aren’t. Only by examining the statements a political actor makes and actions they take can we truly understand to what they are paying attention. So while there has been a great deal of work on agenda setting dynamics, few scholars have focused on mapping the scope of a political actor’s agenda. The vast majority of studies that revolve around the president and his agenda focus on how he shapes the agenda of other actors or how other actors shape the presidential agenda (Edwards & Wood 1999; Eshbaugh-Soha & Peake 2004; Peake 2001; Peake & Eshbaugh-Soha 2008; Olds 2013; Rutledge & Larsen Price 2014). Alternatively, they focus on how presidential agenda setting leads to changes in public attention (Cohen 1995). By only focusing on the interaction between actors, and not on the composition of the agenda itself, we are limiting our ability to understand which issues get on to the agenda. Past studies of agenda setting largely derive the policies on the president’s agenda from State of the Union Addresses. Although there is no argument that the State of the Union address is an important document through which the president communicates parts of his agenda, it is an imperfect indicator for the entirety of the president’s agenda. Instead, it is important to look at !2 other ways presidents communicate their policy priorities. In this paper, I will demonstrate that it is necessary to use a second measure of the presidential agenda. By examining the policy content of presidential budget messages, via the Policy Agendas Project coding scheme, from 1978 to 2008, I will show that the agenda conveyed during the state of the Union is only a partial picture of presidential priorities, and that it is important to understand the intended audience of a message to understand how presidential budget messages unveil additional components of the presidential agenda. Theory Studies of presidential agenda setting have long focused on State of the Union messages in order to understand the presidential policy agenda. While the speech surely does contain a aspects of the presidential agenda, its position as the sole source is based on faulty assumptions. In Paul Light’s book The Presidential Agenda, he states that in interviews with presidential staff, they recommend looking at the State of the Union because the president’s “top priorities will always appear in the message at some point” (Light 1999, p. 6). While it is true that his top priorities will appear in the State of the Union, a president’s list of priorities is more complex than just the top priorities. Policy areas differ in their importance to different audiences and, as not all of his priorities are of interest to the broad audience at the State of the Union, I contend that it is not a complete account of the president’s agenda. The nature of the State of the Union address precludes the president from including all of his policy priorities, requiring that he use some other document to convey his priorities to the rest of government. !3 One characteristic of the State of the Union that makes its content different from other presidential speeches is that the State of the Union Address is a highly partisan event. The president is trying to get support for his agenda, and that support is going to be coming primarily from his co-partisans both inside and outside of government. Considerable research on presidential rhetoric reveals that, while presidents often think of themselves as persuasive speakers, they can not change public opinion (Edwards 2003; Canes Wrone 2006). Rather, presidential rhetorical strength comes from activating parts of the public that already agree with him and having them place pressure on other members of government (Kernell 2007). As this “going public” process is the dynamic at work, it is understandable that presidents would strategically use the State of the Union to address those issues and those people the president needs to pressure Congress to get his policies passed. Additionally, Wildavsky’s “two presidencies thesis” suggests that there are some policy areas in which the president has more discretion (1966). So the president may spend more time addressing those policy areas in which he is seen as having dominance in the public eye. This selectivity means that it is likely that some issues will be addressed rather than others. Finally, the greatest reason why the State of the Union should not be the only measure of the presidential agenda is that the primary audience of the speech is the American public. Press coverage in the days leading up to the State of the Union makes it incredibly clear that Washington insiders of all stripes know the policy areas and positions contained in the State of the Union before the president even leaves the White House to go to the joint session of Congress. As such, the primary audience is not Congress or the bureaucracy; the audience is the American people. Just as the speech is biased by a need to activate co-partisans, the contents of !4 the speech are biased towards dealing with issues that the public is inclined to care about. These include policy areas like health and education, but State of the Union addresses are unlikely to contain rhetoric about government reforms, as the public, while appreciative of a better-working bureaucracy, does not respond to the issue the same way that those inside government respond. Thus, I would argue that what is contained in the State of the Union represents only a portion of the policy agenda that the president wants to achieve. In addition to the many publicly popular policy goals, presidents have other priorities that the State of the Union is a poor venue through which to communicate. Additionally, because presidents are strategic actors sensitive to the fact that different policy tools will help them achieve different types of success (Larsen Price 2012), it seems reasonable to suspect that, while there may be overlap in the policy agendas presented in different documents, there will also be parts of the presidential agenda that will be absent from some documents and will be present in others. As such, it is important for us to examine another set of presidential documents for additional insight into the presidential agenda. To test another document for insight into the presidential agenda, it is first necessary to decide which document to consider. One important criteria was that it occur in all presidencies. One strength of studying State of the Union messages is that they are constitutionally mandated and thus there is an address for every year of every presidency. Another important criteria was that it be a document that explicitly consisted of presidential priorities. By focusing on documents that contained presidential priorities, we are able to say, with some reasonable certainty, that it is an agenda-setting document. The only other type of document that fulfilled both of these criteria was presidential budget messages. These are annual written messages, often only a few pages in length that !5 introduce the president’s proposed budget that he presents to Congress. One way in which these messages are similar to the State of the Union is that they occur annually, and are delivered at roughly the same time of year as the State of the Union, in late January or early February. Additionally, budget messages are rather explicit in the fact that they contain the priorities of the chief executive. As the opening quote of this paper shows, presidents demonstrate their vision for the future of the country with how they think the federal government should spend its resources. While the State of the Union contains rhetoric such as “I will send this bill to Congress,” budget messages are able to communicate shifting priorities such as “we need to do more about health, welfare, and education” and attached to that statement is a budget in which more money has been allocated to those specific policy areas. Also an important characteristic of budget messages is their intra-governmental audience. While any American can look at the budget and the president’s budget message on-line today, the public is not the primary audience for administration budget proposals. Instead, the primary audience is within government, and the bureaucracy, in particular. These are the actors that care about the ordering of presidential priorities and whether he feels that an agency should receive greater or fewer resources. Finally, the issues that matter to the bureaucracy are different than the issues that matter to the public at large. Using my earlier example, the public cares about health and education, and while the relevant bureaucracies care about those issues too, all members of the bureaucracy care about issues such as government reorganization and proposals which will alter their operating procedures to try and increase efficiency. These are issues which the president will not address in the State of the Union, but will address, at some great length, in the !6 budget message. This adds up to a clear need to analyze the policy content of presidential budget messages to see how they shed new light on the scope of the presidential agenda. Thus this paper will test four hypotheses about the presidential agenda contained in these two documents. First, the audience is a major shaping factor in the agenda contained in the message. The budget messages’ intra-governmental audience will lead to increased attention to topics such as the budget (which is a part of the macroeconomic topic area) and government reorganization (which is under the government operations topic area). The mass public audience of the State of the Union will be less interested in these policy areas, thus I expect there to be significantly less attention paid to these policy areas. Second, the two documents will pay different levels of attention to policies in which the president has considerable discretion and involvement. In the State of the Union, presidents will focus on policy areas in which they are considered to have discretion to act. The primary area in which they are seen to have discretion is foreign affairs (Wildavsky 1966). However, even when presidents have the discretion to act, they often feel they must justify their actions to the public. Foreign affairs will receive less attention in the budget messages because the president does not have to spend as much time justifying his behavior to those in government, as they have already given him discretion to deal with those issues. Third, in studying the correlation across policy areas, I expect there to be little or no significant correlation in documents. If the documents were highly correlated, it would signal that they deal with the same policy areas at roughly the same rates. But I as I have discussed, the difference in audience assures that most policy areas receive differing levels of attention in the two documents. While there may be a few policy areas that have similar patterns of attention !7 across the two documents, I expect that most topics will have a distinct presence in each document, signaling that the president’s agenda is not identical in all agenda setting documents. Finally, in studying the correlation of topics across years, I expect a positive relationship between the two documents, but with moderate levels of correlation. Prominent theories of information processing point to the limited attention of political actors as a major constraint of agenda size (Jones and Baumgartner 2005). This is particularly true of institutions, like the presidency, which are serial processors. Because of this limited attention capacity, there should often be overlap in the selection and prioritization of policy topics. What is important, however, is the lack of perfect correlation and the infrequency of very high correlation. Very high correlation would signal a duplication of agendas; the same content with the same prioritization in a given year. I hypothesize we will not see that. Instead, we will see moderate to low levels of correlation between documents in most years. This would show the consistency that is natural when comparing messages from the same person, but show the divergence that is inherent when messages are used strategically to reach different audiences. Data and Methods Central to my analysis of the scope of the presidential agenda is a way of distilling the policy content of the messages down to an analyzable structure that is consistent across years and document types. The Policy Agendas Project coding scheme provides a structure for coding the policy content of budget messages and a set of clear coding rules that allow the new data set to !8 be compared with their established dataset of State of the Union messages1. The Policy Agendas’ coding scheme is composed of 20 major policy areas and over 220 minor policy areas. The data set also extends from 1946 through to present. Each observation is assigned only one major topic and one minor topic nested within that major policy area. This creates a backwards-compatible time series, allowing scholars to trace attention to issues. It also results in a one-to-one relationship between the number of observations and the proportion of the document that addresses a specific policy area. The Policy Agendas Project has a number of coding rules designed to help with this task of assigning only one code. The primary coding rule is that in the instance that an observation references multiple policy areas, the one that is most strongly emphasized gets its code assigned. If two policies with in the same major topic area are addressed, they are assigned to the general topic for the major category. In the, usually rare, instance that an observation is equally weighted between two or more codes in different major topic areas, the numerically lower code is assigned. In this project, I followed all of the coding rules exactly as they are set out by the Project to allow a direct comparison to their work2. Given the desire to match the Policy Agendas Project methods, the data structure of the budget messages also follows the structure of the State of the Union data set. The State of the Union data set is characterized by the speeches being broken down into their grammatical subunit: the quasi-sentance. A quasi-sentence is the text between periods and semi-colons; each bit of text is a complete thought that can stand on its own. Then each quasi-sentance is given its 1 The data used here were originally collected by Frank R. Baumgartner and Bryan D. Jones, with the support of National Science Foundation grant numbers SBR 9320922 and 0111611, and were distributed through the Department of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. Neither NSF nor the original collectors of the data bear any responsibility for the analysis reported here. 2 See the Policy Agendas Project Master Topics Codebook: http://www.policyagendas.org/page/topic-codebook. !9 own major and minor topic code. This structure allows the coder to examine not only which topics are addressed in the speech, but the proportion of attention that a given topic receives within the speech as a whole. This method of parsing messages and coding each quasi-sentance was then applied to the presidential budget messages. To test my hypotheses, I rely on graphical analysis and a study of correlations between data sets. By examining individual characteristics of the data, such as the length of documents and the distribution of attention to policy areas, it is possible to understand the relationship between the documents. Additionally, I calculate pairwise correlations of the relationship between State of the Union addresses and budget messages by both year and policy area. Correlations are often dismissed in political science because of the fact that correlation is not causation. Many things in the universe display similar trends over time and space without causing each other. In fact, it is just that absence of causation that draws me to studying the correlation between data sets. The scope of the presidential agenda is the true variable of interest in my study of presidential agenda setting. However, the scope of the agenda is not directly observable. Instead, we must rely on measures such as the State of the Union and presidential budget messages. I do not think that attention to a policy in either one of these measures in any way causes attention to the policy in the other. Instead, I theorize that both are signals of the underlying variable of interest, the presidential agenda. However, by correlating these data, I am able to see the way in which each message is giving repetitive information versus distinct, new information about the presidential agenda and how that agenda may be tailored to the specific audience of the message. !10 Results Following the coding of the data, it is important to examine the ways in which the two documents are similar and different. This is a key way to test the hypotheses. First, it is important to study the distribution of attention to each policy area in presidential budget messages, as it will allow us to answer the first and second hypotheses. Figure 1 shows the proportion of attention paid to each policy area in both presidential budget messages and State of the Union addresses over time. One aspect of the data that is immediately obvious is the considerable variation in the amount of attention across policy areas and across documents. Many policy areas receive hardly any attention in either State of the Union addresses or budget messages, such as civil rights, agriculture, environment, immigration, transportation, housing, and international trade. None of these topics make up even 10% of the contents of either document in any year in this dataset. Another observation, visible from figure 1, is that some other policy areas receive greater levels of attention in both messages, but often at different points in time. Health, labor, education, law, crime and family, social welfare, and defense all receive substantial attention from presidents, although they might receive more attention in one document than another. A key component of this greater level of attention is the fact that it is not constantly high. It is often characterized as a spike in the proportion of attention the issue receives and then a subsequent return to the “regular” patterns of lower attention. A third finding is that there are some policy areas that take up different proportions of attention in the two documents. Three issues, macroeconomics, international affairs, and government operations each take up sizable chunks of the presidential policy agenda, but each !11 !12 Proportion of Document 2010 1990 2000 2010 Housing Energy Health 1980 2000 Year 1990 International Affairs State of the Union 1980 International Trade Space, Science, Tech. 2000 Social Welfare Law, Crime, and Family 1990 Environment Education 1980 Civil Rights Macroeconomics 2010 1990 2000 2010 1980 Budget Message 1980 Government Opperations Banking Immigration Agriculture 1990 2000 Public Lands Defense Transportation Labor 2010 Figure 1. The Distribution of Attention in Each Policy Area, 1978 to 2008 .6 .4 .2 0 .6 .4 .2 0 .6 .4 .2 0 .6 .4 .2 0 Figure 2. Pairwise Correlation between Budget Messages and State of the Union Addresses, by Policy Area 0.7 0.525 0.35 0.175 0 Significant at the 0.05 level Public Lands Government Opperations International Affairs International Trade Space, Science, Tech. Defense Banking Housing Social Welfare Law, Crime, and Family Transportation Immigration Energy Environment Education Labor Agriculture Health Civil Rights -0.35 Macroeconomics -0.175 has a different venue. Macroeconomics, at various points in time, has taken up considerable attention in both budget messages and State of the Unions, but seems to receive much more attention in budget messages than in State of the Unions. In one of its highest years, the president dedicated roughly 40% of his State of the Union address to macroeconomics, while in that same year dedicated over 60% of his attention to the same issue (in 2001). You see similar dynamics in the policy area of government operations. This is a topic to which the president dedicates little attention in his State of the Union Address. The opposite is true in international affairs, where there is far less attention in the budget messages than there is in the State of the Union. Finally, we examine how the documents correlate with each other by topic and by year. Figure 2 shows the correlations by policy area, while Figure 3 shows the correlations by year. !13 Figure 3. Pairwise Correlation between Budget Messages and State of the Union, by Year 1 0.75 0.5 0.25 0 -0.25 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 Significant at the 0.05 level Figure 2 shows that only four policy areas are strongly enough correlated in order for the relationship to be considered statistically significant (macroeconomics, health, education, and energy). Even of those, there is considerable variation in the level of correlation, ranging from energy (0.69) to education (0.41). Ten policy areas are positively correlated, although correlated at less than 0.3, a very weak relationship by most accounts. Five policy areas are correlated in the negative direction (in which an increase in one document means a decrease in the other), but there too, the relationships are very weak, never getting higher than -0.18. This supports hypothesis three: that the correlation across topics is likely to be low, with little statistical significance. Figure 3 supports the forth hypothesis that there is moderate correlation between the documents over time. Here 17 out of 31 years reached statistical significance and all but one year were positively correlated. Only 10 years were correlated at a rate less than 0.3, but only5 years were correlated at a level greater than 0.75. !14 Discussion The results support all four of the hypotheses. The first finding is that a number of policy areas receive little attention from the president in either document. This may be due to three possible underlying dynamics: either these are policy areas to which the president only pays minimal attention, the president pays attention to many topics in equal amounts (although this seems to be easily dismissed by examining macroeconomics and government operations categories), or that presidential attention in these areas is demonstrated through other documents. With the exception of international trade, all of these policies fall within the scope of domestic policy. Wildavsky’s “two presidencies thesis” would suggest that presidents have a harder time getting what they want in domestic policy (1966). So perhaps, these low levels of attention suggest that when the president wants to get involved in these policy areas, he does not fold this intention into larger policy speeches, but in fact acts more directly, working within the policy subsystem or by introducing specific legislation that does not get mentioned in State of the Unions or budget messages, as we see in agriculture, where the Freedom to Farm Act of 1996 is completely absent. This suggests that there may still be aspects of the presidential policy agenda that are absent from these two major agenda setting speeches. A second finding was that some policy areas receive substantial attention in both documents at specific points in time. This conforms with the idea that presidents have some policy areas in which they are expected to regularly pay some measure of attention, although at times that level of attention may rise to substantial levels, where that single topic can make up 20 to 30% of a given document. Whether that variation is driven by personal interest or the political context of the time is uncertain. What is clear is that presidents can’t ignore these policy topics !15 and when they do get on to the agenda, they often take up considerable attention. For example, social welfare policies regularly take up 10 to 15% of the contents of State of the Unions and budget messages, but when President Bush was interested in privatizing Social Security, the topic made up approximately 30% of his State of the Union address in 2005. The third finding, surrounding the substantially differing levels of attention in macroeconomics, government operations, and international affairs, supports the first and second hypotheses: the audience of the document matters and that presidents use the State of the Union to talk about issues in which they have considerable discretion. In the case of macroeconomic and government operations, these are areas in which the president needs to spend more time explaining his stance to his partners in government, while not as much time to explain to the American people. The opposite is true in one policy area: international affairs. This is the one policy area in which we see considerable attention in State of the Union addresses, but far less attention in budget messages. These spikes come in the wake of military action around the world suggesting that the document’s audience is key to the policy content it contains. The presidential agenda on the international stage requires less explanation for the president's intra-governmental audience and more explanation for the American people. This variation in the level of attention across policy areas demonstrates that presidents have discretion over what policy areas they choose to get involved. Those policy areas in which there is little-to-no presidential attention in State of the Unions and budget messages could be categorized as primarily discretionary policy areas. In these, the president gets involved only when he desires to make policy or there is a crisis of some kind. Energy is one such example, where there is very little attention except in the wake of the Oil Crises of the 1970s. In those !16 policy areas in which we see greater presidential attention, whether it is in one agenda-setting message or both, we are seeing those policy areas in which presidential participation is compulsory. Some of these areas contain presidential attention all the time, while others have the president’s attention more at some times than others. This finding is an important step towards building a typology of presidential agenda discretion, just as Walker built a typology of agenda discretion for the U.S. Senate (1977). Finally, we examine how the documents correlate with each other by topic and by year. It is first necessary to establish what these correlations would mean, as we are considering each as an indicator of the underlying presidential agenda. In figure 2, a high correlation across policy areas means that the president talks about a policy area at the same levels in both documents. For example, energy policy is highly correlated because he is always talking about it at the same level across documents; if there is a lot of attention to energy in the State of the Union, then there is a lot of attention in the budget messages, and if there is only a little attention in the budget message, than there is only a little attention in the State of the Union. A low correlation means that there are very different patterns of attention to that policy area in the two documents. For example there is a near zero correlation regarding labor policy. This means there is no relationship in attention to labor policies between the two documents. An issue like international affairs would seem to be weakly correlated across documents, but is not statistically significant because the relationship doesn’t hold up across the entire time series (See figure 2). Quite a number of issues fail to reach the threshold necessary for statistical significance. Indeed those issues that do achieve significance fall squarely into to categories: those that regularly receive attention from the president (macroeconomics, health, and education) and those issues which do !17 not receive attention except under extraordinary circumstances (energy). This supports hypothesis three, that there would be little or no statistically significant correlation in policy areas across the two documents. When considering the correlations of presidential documents across time, collapsing all issues, we see a different pattern. While we confirm the hypothesis that the relationship between documents over time is positive and often significant, perhaps the most interesting aspect is the extent to which they are, in many years, distinct documents. A clear piece of evidence to support my theory that we need to consider more than just the State of the Union is the fact that only 5 out of the 31 years have a correlation above 0.75. The vast majority of years correlate less than 0.5 (17 out of 31 years). Here high levels of correlation demonstrate that the policy agenda in the two documents is largely the same, while low levels of correlation speak to divergent agendas across documents. The prevalence of moderate to low correlations between agenda setting messages, particularly given the fact that they are delivered at roughly the same point in the year, is evidence that policy messages are differently utilized to maximize their impact, given their audiences. Conclusion Eminently clear from this work is the conclusion that there is something different about the president’s agenda in budget messages than in State of the Union addresses. I have proposed a number of ideas about what might motivate the differences between the documents through out this paper. My primary idea is that these messages have different audiences. The primary audience of the State of the Union address is the American public, this causes these speeches to !18 deal heavily with issues of importance to the public such as education, jobs, and healthcare, plus presidents are forced to justify their actions on foreign relations. The audience for the budget messages are actors with in government, and the federal bureaucracy as the largest component. These actors care about whether the funding to their department is going to grow or shrink and whether the president is going to pursue any kind of bureaucratic reorganization. This leads to a great deal of attention to government spending and the budget deficit, items which fall in the macroeconomics category, and government operations, the category containing issues relating to the bureaucracy. These different audiences, with their different concerns, leads to the documents containing different policy content, even within the same year. My next step is to continue exploring this data set. One aspect that requires further examination is the time series-cross section structure of the data. When studying these presidents, particularly when using correlations, it is important to remember that there is no way to establish any kind of causation. Thus, future work on the causes of the presidential agenda need to run models using time series-cross section with president-fixed effects. This could allow us to control for any personality-type causes in the variation and simply examine the institutional and audience-based differences. Another way that this data set could be continued is to assign multiple codes to budget message observations. The method used in this paper, of assigning only one code, comes from the Policy Agendas Project, which wrote the lower code rule because observations with multiple policy areas were rare in their datasets. Unfortunately, the budget messages are regularly populated with observations spanning multiple major topics with equal levels of attention applied to all. Regularly, those statements contain mentions of either macroeconomics or health, causing !19 these two policy codes to be loaded with observations that call attention to a broad number of policy areas. By allowing multiple codes for these kinds of observations, we would be able to get a better sense of the distribution of policy priorities that presidents place in their budget messages. Because the goal of this project is to understand the full scope of attention, it is vital to extract as much information as possible, rather than allowing some of the data to be swallowed into other policy categories. Presidents are faced with the expectation that they respond to problems in all policy areas. Yet research on attention tells us that there are limits to the agenda space (Jones & Baumgartner 2005). Previous studies of the presidential agenda have primarily focused on his ability to set the broader governmental agenda. Yet there are still questions as to the scope of the president’s attention. It is clear from this study that some issues are more regularly on the president’s agenda than others, but it is also clear that in order to get a complete picture of the president’s agenda it is necessary to consider more sources than just the State of the Union. This study, which is a step in the right direction by incorporating budget messages, still does not give us a sense of the entire agenda. Only by keeping an open mind and continuing to analyze presidential documents will we be able to understand the full range of policy demands on the president. !20 Works Cited Bachrach, Peter and Morton S. Baratz. “Two Faces of Power.” American Political Science Review 56 (4). Bush, George W. 2001. “The Presidential Budget Message” in the Federal Budget. Published by the Office of Budget and Management. Baumgartner, Frank. 2001. “Political Agendas.” Canes-Wrone, Brandice. 2006. Who Leads Whom: Presidents, Policy, and the Public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cohen, Jeffrey E. 1995. “Presidential Rhetoric and the Public Agenda.” American Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 87-107. Michael D. Cohen, James G. March, and Johan P. Olsen. 1972. A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice. Administrative Science Quarterly 7: 1-25. Edwards, George C., III. 2003. On Deaf Ears: The Limits of the Bully Pulpit. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Edwards, George C., III and B. Dan Wood. 1999. “Who Influences Whom? The President, Congress, and the Media.” The American Political Science Review 93 (2): 327-344. Eshbaugh-Soha, Matthew and Jeffery S. Peake. 2004. “Presidential Influence Over the Systemic Agenda.” Congress & the Presidency 31 (2): 181-201. Finocchiaro, Charles J. and David W. Rohde. 2008. “War for the Floor: Partisan Theory and Agenda Control in the U.S. House of Representatives.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 33 (1): 35-61. !21 Greenstein, Fred. 2009. The Presidential Difference, 3rd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Jones, Bryan D. and Frank R. Baumgartner. 2005. Politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Kernell, Samuel. 2007. Going Public: New Strategies of Presidential Leadership. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. Kingdon, John W. 1995. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers, Second Edition. Larsen Price, Heather A. 2012. “The Right Tool for the Job: The Canalization of Presidential Policy Attention by Policy Instrument.” The Policy Studies Journal 40 (1): 147-168. Light, Paul. 1999. The President’s Agenda. John Hopkins University Press, 3rd Edition. Olds, Christopher. 2013. “Assessing Presidential Agenda-Setting Capacity: Dynamic Comparisons of Presidential, Mass Media, and Public Attention to Economic Issues.” Congress & the Presidency 40 (3): 255-284. Peake, Jeffery S. 2001. “Presidential Agenda Setting in Foreign Policy.” Political Research Quarterly 54 (1): 69-86. Peake, Jeffery S. and Matthew Eshbaugh-Soha. 2008. “The Agenda-Setting Impact of Major Presidential TV Addresses.” Political Communication 25: 113-137. !22 Rutledge, Paul E. and Heather A. Larsen Price. 2014. “The President as Agenda Setter-inChief: The Dynamics of Congressional and Presidential Agenda Setting.” The Policy Studies Journal 42 (3): 443-464. Schattschneider, E. E. 1957. “Intesity, Visibility, Direction and Scope.” American Political Science Review 51 (4). Walker, Jack L. 1977. “Setting the Agenda in the U.S. Senate: A theory of Problem Selection.” British Journal of Political Science 7: 423-445. Wildavsky, Aaron. 1966. “The Two Presidencies.” Trans-Action 4. !23