poetry box ideas - Scottish Poetry Library

advertisement

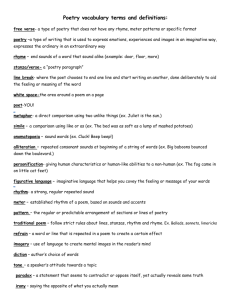

poetry box ideas SOUND AND RHYTHM Sound and rhythm are the motors and music of poetry. One of the things that makes a poet great, like a great band or composer, is a distinctive sound. One of the things that makes a poem great is the way its sound and meaning mesh and support each other. ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Sound is not the same as spelling. Get away from the spelling and into the sounds it represents. ___________________________________________________________________________________________ As reader or writer, feel the structure of a poem’s sound. For example, do you close or round your lips to make a particular sound? Or do you move your tongue to say it? How and to where does your tongue move? READ IT ‘Dream Variations’ by Langston Hughes, in the Presiding Spirits poem cards Words in this type are in the glossary on the back of this sheet. To my ear, the rhythm of this poem is jazzy and dream-like. Rhythm is mostly about how many stresses are in a line and where they go, so read out ‘Dream Variations’ paying attention to the stresses. Most lines have two, but the number of unstressed syllables is more variable. The first stress is mainly on the second or third syllable in a line, but note how Hughes hammers home ‘Dark’, ‘That’ and ‘Black’ by putting them right at the start of short lines. The second stress is usually on the very last syllable, emphasising words like ‘wide’ and ‘done’. When Hughes puts the stress on the second last syllables in lines 5 and 7, ‘evening’ and ‘gently’, it slows the poem down as he moves it from day into night. Can you identify any further rhythmic changes in the second stanza? What effect do they have? Let’s move on to rhyme. In both stanzas of ‘Dream Variations’, line 2 rhymes with line 4, while line 6 rhymes with 8. Hughes has used very straightforward full rhyme. Many contemporary poets use a more interesting and subtle form of rhyme, known variously as half rhyme, slant rhyme or near rhyme, to great effect. For example, read Stevie Smith’s ‘Scorpion’, paying attention to the rhymes. ‘Dream Variations’ also contains alliteration – d in ‘day is done’ or of t and l in ‘tall, slim tree’. But something subtler is going on. The first stressed word in each of the first four lines begins with a sound pronounced by the lips and not the tongue: f, p and w(h). However, as the rest of the stanza moves through evening into night, the first stressed syllables all start with sounds made with the tip of the tongue: r, n, d and th. What changes does Hughes make to this pattern in the second stanza? How does all this use of sound shape your understanding of ‘Dream Variations’? When you read other poems, look out for these and other effects. Listen for the different ways in which various writers use sound. For instance, read and compare Geoffrey Hill’s ‘Funeral Music’, Randall Swingler’s ‘The Day the War Ended’, Marianne Moore’s ‘The Steeple Jack’ and Philip Larkin’s ‘This Be the Verse’. WRITE IT When Hughes wrote about race, African Americans were still very much oppressed. Write a stanza about something that affects how people treat you or someone you know – maybe appearance, ethnicity, accent or disability. The stanza should have no fewer than five lines and no more than nine. The rhythm of the lines should vary too; make sure you don’t get stuck in the same rhythm for every line. Next, change some of the words to make a second, very similar stanza. Use words that sound similar to the original ones but that still make sense in the poem. (If you struggle to think of any, dip into the dictionary at a relevant letter.) Change the number of stresses in some of the lines to make a third stanza. Then write a fourth, with more changes in words and rhythm. What effects does each change produce? Which changes work best? Choose the best two stanzas and see whether they work together as a poem. Glossary alliteration: repetition of a consonant sound, mostly but by no means always at the beginning of a syllable – eg, fatuous in flowers. assonance: repetition of the same vowel sound with different consonants – e.g., made face. consonance: repetition of the same consonants before and after a vowel – e.g., (diffi)cult colt. end rhyme: rhyme of any kind at the end of a line (the most usual position). full rhyme: involves two or more words in which the vowel sound and any following consonants are the same – eg, sun done or tree me. half rhyme/near rhyme/slant rhyme: involves related but non-identical vowels and/or consonants. There are many variations, such as assonance and consonance. For detailed information and analysis, see my ‘Reasoning Rhyme’ posts at http://tonguefire.blogspot.com. internal rhyme: rhyme inside a line. See the last two lines of Blake’s ‘The Garden of Love’ for a clear and straightforward instance. Les Murray’s ‘Honey Cycle’ has internal rhyme scattered over various positions in several of its lines. stress: any syllable(s) in a word, phrase, sentence or line of poetry where the emphasis goes – eg emphasis or To fling my arms wide. www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk Scottish Poetry Library More reading and listening There’s no substitute for reading widely in different forms and styles – and other languages, if you can. The following are a few suggestions in English to get you started. Don Paterson (editor) 101 Sonnets Not all the sonnets in this brilliant little anthology are rhymed, but the vast majority are. Les Murray’s ‘Honey Cycle’ is a riot of end rhyme, internal rhyme, alliteration and consonance. The book has a useful introduction and brief notes, too. Gerard Manley Hopkins It’s impossible to read Hopkins and not think about what the consonants and vowels in each line are doing. A great poet for exploring explosive sound. Seamus Heaney (translator) Beowulf Heaney manages to remake this ancient poem in contemporary English but keep a strong and effective flavour of the Anglo-Saxon alliterative line. www.poetryarchive.org A remarkable online collection of historic and contemporary recordings of British, Irish and American poets reading from their work. You can browse by poet, form or theme. The Poetry Archive has also produced a range of fabulous CDs from its contemporary recordings, several of which are in the library here. ‘Dream Variations’ by Langston Hughes is reprinted in the Presiding Spirits postcards produced for Poetry International 2006. You can also find it in Collected Poems (Vintage, 1995) and other anthologies. Andrew Philip Andrew Philip was born in 1975. His pamphlet Tonguefire was published by HappenStance in 2005 and he was one of the Scottish Poetry Library’s new voices for 2006. Andrew lives in Linlithgow and is a member of Edinburgh’s Shore Poets. www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk Scottish Poetry Library