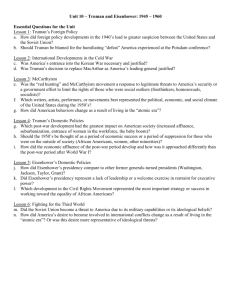

Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson

advertisement