Chapter 5: Family Assessment Sonja J. Meiers, Norma Krumwiede

advertisement

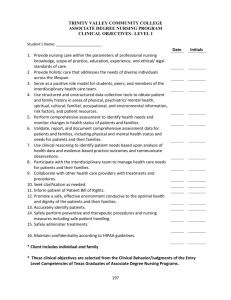

Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell Chapter 5: Family Assessment Sonja J. Meiers, Norma Krumwiede, Sharon A. Denham, & Sue Bell Chapter Objectives 1. Differentiate between individual, family, and community assessment. 2. Discuss assessment that includes the predictive and protective factors that influence the health and illness of individuals, families, communities, and populations. 3. Explain ways that genograms, eco-grams, and eco-maps can be used to assess family from an ecological point of view. 4. Describe ways that computer-based geographic information systems can be used to understand family, community, and population health needs. 5. Evaluate ways that personal and family health records might improve health care outcomes. 6. Recognize ways that family history information, genetics, and genomics influence health, disease prevention, treatments, screening, and outcomes. Chapter Concepts Assessment Clinical Nursing Judgments Ecomap Family Unit Assessment Family Pedigree Genetics Genogram Geographic Information Systems Individual Assessment Nursing Process Social Capital Spiritual Assessment Chapter Introduction When nurses meet individuals in any type of care setting, nurses prepared to think family are apt to be most comprehensive in their assessments. Historically, the focus of health and illness assessments has been on the factors that influence individuals. Several nursing theorists have Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 4 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 2 discussed the role of families in health and illness care (Neuman & Fawcett, 2011), but nurses have often viewed the family as the context of care. Although family members might be included in discussions if they are present, traditional practices mean that these discussions are seldom intentionally planned with family units. Documentation of the family conversations or assessments is not often found in the person’s record. The accuracy and breadth of assessment data might be improved by purposely including family member input and family member perceptions of things like the health alterations, illness events, symptoms, or disease management. A comprehensive family assessment might provide better understandings about situations. Thinking family could increase awareness of the breadth of possible causative factors for symptoms (Tanner, 2006). An intentional approach to family assessment includes the individual linked with the family unit and household perspectives. These things could provide a clearer more accurate picture of individual’s needs and describe risk factors, environmental threats, community and social networks, availability or lack of resources, and family strengths. Chapter five of the textbook introduces nurses to ideas of intentionally thinking family during clinical assessments. Holistic assessments go beyond physiological systems and include a holistic perspective of the family (e.g., dynamics, communication, interactions). Assessments that include the family household and neighborhood or community perspectives have potential to address problems linked with the family unit. This chapter proposes that health outcomes can be improved when the predictive factors (those that cause risk or benefit to health) and protective factors (those that provide a buffer to illness, injury, or disability) are simultaneously considered. This chapter reviews critical aspects of individual, family, and community assessments and describes ways to do a more comprehensive approach to Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 3 assessment. Risk assessments that take into account predictive factors, protective factors, and the social determinants of health are explained. Using a Family Framework or Theory to Guide Assessment Family nursing scholars have developed tools that can assist nurses approach family assessment systematically. Assessments can provide insights about family types or structure, ways members function or accomplish family work, and interactive processes that influence health and illness. When considering the family type or structure, the nurse may need to identify the key members, how they are related or emotionally connected and who would most likely be caregivers. Persons that will fulfill these functions will be important when it comes to goal setting and strategy development. Knowing family members’ typical roles and actions can help understand the household where individuals live, places where health is enacted and illness care given. This valuable information can assist nurses as they inform, educate, and coach the individual and family unit prepare for new roles to manage things like an acute care injury or a chronic illness. Nurses that think family assess typical member processes, determine whether open or closed communication occurs, and identify whether boundaries will support or hinder care outcomes. As students learn more about the ways unique families function, they can better choose care approaches, identify optimal ways to share difficult news, and gain skills in sharing information when families face difficult illness or disability trajectories. Nurse that think family use family models to describe complex family lives and factors that influence health and illness experiences (Table 5.1). For example, the Calgary Family Assessment Model (CFAM) is a comprehensive family assessment that can guide examination of structural, developmental and functional dimensions (Wright & Leahey, 2009). The Family Management Style Framework encourages nurses to consider implications of complex family life Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 4 and parenting goals as individual’s needs are considered during the assessment at various developmental stages (Knafl, Breitmayer, Gallo, & Zoeller, 1996). In 1995, the Family Nursing Research Team at Minnesota State University, Mankato began development of the Family Nursing Construct Framework to guide the delivery of family focused nursing actions based on an initial grounded theory study with families managing side effects of chemotherapy for treatment of cancer (Krumwiede, et al., 2004). Three constructs were identified (i.e., Family Information, Family Vigilance, Family Waiting) that suggest ideas about assessments and nursing actions (Table 5.2). This framework continues to be informed by discovery and clarification of other constructs to use during assessments. As nurses learn about various family constructs, they can incorporate them into a plan of care and address them through intentional individual-nurse-family partnerships. Family focused nurses collaborate with individuals and their family units to identify goals and care strategies aligned with their values and needs. Nursing actions or interventions are used to support the family in valued ways. Table 5.1 Family Models: Attention to Family Structure, Functions, and Processes Model Structure Functions Processes Family Health Model • Family microsystem • Family economic Core processes: • Caregiving • Family data status (Denham, 2003) • Developmental • Cultural assessment • Cathexis information • Neighborhood data • Celebration • Change • Household niche data • Larger community • Family health • Family mesosystem • Communication routines • Family macrosystem • Connectedness • Family rituals • Chronosystem • Coordination (normative and nonnormative events) Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell • Family genogram •Instrumental • Expressive Calgary Family • Family ecomap functioning: functioning Assessment Model • Family development Routine activities of • Emotional (Wright & Leahy, • Family lifecycle daily living (e.g., communication 2009a) eating, sleeping, • Verbal and preparing meals, caregiving activities, health promotion, appraisal of symptoms and management of illness) Family Systems Stressor-Strength Inventory (FS3I) (Hanson, & Mischke, 1996) nonverbal communication • Circular communication • Problem solving • Role enacting • Influence and power • Beliefs • Alliances and coalitions • Family demographics • Family systems • Family systems (name, member stressors (general and completing assessment specific) form, ethnic and • Family systems religious backgrounds) strengths • Family reason for seeking assistance stressors (general and specific) • Family systems strengths The Friedman Family •Identifying data •Developmental stage Assessment Model and history of family (Short Form) •Environmental data (Friedman, 1998) Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 • Affective functions • Socialization • Communication patterns functions • Power structure • Health care functions • Role structure • Family stress and • Family values coping 5 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell Table 5.2 The Family Nursing Construct Framework Family Nursing Nursing Assessment Family Nursing Action Construct Family Information Ask “Which family member Complete family assessment, family keeps track of family health genogram and ecomap. information?” Identify family member who retains Note how rapidly the health information. individual is identified. Explain health care team’s goal of sharing Once you begin to interview family health information that is useful to the family informant, note how patient and family health. freely this information is shared. Consider priority of family for information and giving essential Assess the family’s need for information while considering HIPPA information. rules and regulations in the institution. Recognize that HIPPA was written for protection related to insurance portability, not to withhold information from family members. Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 6 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell Family Vigilance Observe the absence and/or presence of family members. Encourage Family Presence Encourage family members to stay as close to ill patient as they choose. Invite family members to stay overnight in room. Invite family members to bedside and explain equipment and medical treatment, technology and nursing interventions. What are the visiting patterns of the family members? Are the family members exhibiting signs of ‘Family Hovering’ when at the bedside? Utilize Nurse Presence Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Stay close to patient & family Explain nursing actions Interpret medical directives Reassure family 7 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell Family Waiting 8 Observe family members that Encourage family members to remain are physically present or are with the patient as they choose. present from a distance. Identify the lead family informant. Ask “Which family member do you want me to contact?” Encourage family members to create a phone tree. Ask “Who is the main communicator for the family?” Allow family members to remain in the hospital or other health care setting. Assess the family’s level of understanding. Be careful to give time increments that are realistic. Assess the family’s anxiety level. Keep family members updated on patient’s status while in care departments, Ask family members their procedures, or surgery. perceptions of perceived threats. Provide updates at regular intervals. Explain timeframe to expect next update of information. Completing a Family Focused Assessment Best quality and safest health and illness outcomes occur when nurses eliminate personal biases and assumptions while completing comprehensive assessments. Nurses need to know about various and relevant forms of assessment that support protection against illness, health promotion, and reduction of risk factors. Additionally, nurses need to be able to discern social determinants of health, be prepared for emergencies, and know responses should disaster occur. Students can be supported in learning strong communication skills during the conduct of assessments that enhance the individual-nurse-family collaboration. Students might initially find it difficult to think simultaneously about individual and family needs during assessments. This approach might seem awkward initially and students will likely need chances to practice these Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 9 skills of simultaneously considering individuals and families. They can be supported in learning these new and complex behaviors through faculty coaching, role playing, simulation scenarios, or supervised practice. Students are exposed to ideas about individual assessment in many nursing courses and textbook readings. However, assisting students to think family will entail intentional teaching actions such as considering family unit needs and the influences of member relationships, family member roles, and family resources relevant to the health or illness care need. Use of an ecological perspective can help students think family as ideas like community, genetics, culture, ethnicity, social capital, and spirituality are introduced. Students need guidance as they learn to think and practice holistically. Tools like the genogram, ecomap, and geographic information systems (GIS) can also help students think critically about individual and family care needs. Most often, when nursing assessment of an individual occurs, family is viewed in the background (Potter, Perry, Stockert, & Hall, 2012). Typical assessments conducted during an acute episode focus on history of present illness, symptom analysis, physiological system review, current medication analysis, review of allergies, and analysis of relevant laboratory findings (Bickley, 2002). However, analysis of potential environmental risk factors predictive of symptoms or injuries might also be necessary (Jensen, 2011). Nurses may investigate the typical stimuli influencing symptoms and potential factors at the individual, family, and community levels that can be altered by nursing actions (Roy, 2009). In other words, as individual assessments are completed, students are challenged to think family and consider the implications of family focused assessment during family engagement and in planning collaborative actions during health or illness experiences. Individuals have strengths and weaknesses, whether suffering from an illness or simply managing a usual developmental transition. Students also Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 10 need to learn ways to systematically uncover family strengths, weaknesses, and protective factors whenever assessments are completed (Bellinger, 2012). A health history also focuses on sociocultural, emotional, and other relevant family factors that may influence the health and illness experience. Genetic Information Advances over the last 30 years have altered knowledge about the human body and disease. In 2003, a 13-year project known as the Human Genome Project was completed by the United States Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health (U.S. Dept. of Energy, 2012). The project, formally started in 1990 and completed in 2003, aimed to identify 20,000 - 25,000 human genes and make them accessible for biological studies. From the beginning of the project, ethical, legal, and social concerns were raised. Thus, part of the project’s annual budget was devoted to an office that considered questions around use of genetic information. The project provides a wealth of information that has profoundly altered the ways human biology is viewed. It is a new horizon with great potential to reshape many life aspects. Some potential is linked with molecular medicine and the improvement of disease diagnosis and detection (Drell & Adamson, 2003). Molecular medicine at this level has resulted in development of new drug designs and gene therapy to treat disease (Drell & Adamson, 2003). Table 5.3 identifies some important questions about societal concerns to be considered as a result of emerging genetic information. Faculty can discuss these ideas with student nurses to enhance student sensitivity to family focused care that considers issues of privacy, confidentiality, and moral actions that influence individuals, family unit, and nursing practice. Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 11 Table 5.3 Societal Concerns Linked with Genetics Societal Concerns Fairness in the use of genetic information Questions Raised Who should have access to personal genetic information? How will it be used? Is it fair or right to share information with family members even though they might not want to have the information? Privacy and confidentiality Who owns and controls genetic information? What are the implications for health care coverage by insurance companies if genetic information is known from generation to generation? Psychological impact and stigmatization How does personal genetic information affect an individual and society’s perceptions of that individual? How does genomic information affect members of minority communities? How will genetic information influence family relationships? Reproductive issues Do healthcare personnel properly counsel parents about the risks and limitations of genetic technology? How reliable and useful is fetal genetic testing? What are the larger societal issues raised by new reproductive technologies? Clinical issues How will genetic tests be evaluated and regulated for accuracy, reliability, and utility? How do educators prepare healthcare professionals for the new genetics? How do nurses prepare the public to make informed choices? How does a society balance current scientific limitations and social risk with long-term benefits? Uncertainties Should testing be performed when no treatment is available? Should parents have the right to have their minor children tested for adult-onset diseases? Are genetic tests reliable and interpretable by the medical community? Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 12 Table 5.3 Societal Concerns Linked with Genetics Societal Concerns Conceptual and philosophical implications Questions Raised Do people’s genes make them behave in a particular way? Do genes influence how families interact? Can people always control their behavior? What is considered acceptable diversity? Where is the line between medical treatment and enhancement? Health and environmental issues Are genetically modified foods and other products safe to humans and the environment? How will these technologies affect developing nations’ dependence on the West? Commercialization of products Who owns genes and other pieces of DNA? Will patenting DNA sequences limit their accessibility and development into useful products? Are vulnerable populations excluded if DNP sequences become privately owned? * Adapted from Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues (2011) <http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/elsi.shtml> Genetic information can also be used to track historic migration patterns. According to scientists in the International HAPMAP 3 Consortium, over 1,100 individuals representing 11 global populations have been sequenced and progress is being made in identifying human genetic variants. However, much is still unknown about inherited human diseases and disease protection (The International HAPMAP 3 Consortium, 2010). Translation of this information into useful practice knowledge and interventions is just beginning to emerge. People have 99.9% of their genetic material in common with other humans, but geneticists are working to uncover the differences and meanings in the remaining 0.1% and their effect on human susceptibility for disease (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2011). A goal is the enhancement of drug effectiveness and therapeutic value. For example, tamoxifen has been used as the endocrine treatment of choice for estrogen receptor positive breast cancer for over 30 years. Tamoxifen has Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 13 been found to reduce the incidence of relapse and, in about half of those breast cancer patients that relapse, it provides a positive clinical response. However, breast cancer can become resistant and non-responsive to tamoxifen, but no mechanism for this development was understood. It is possible that human genetic variants play a role. Genetic research recently found that the BRCA4 gene was a predictive factor for poor progression-free survival and clinical benefit in women with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer (Godinho, et al., 2012). Take some time to help students become more aware and sensitive to the hopes and issues that genetic research and related treatment modalities can pose for families and their relationships. References Bellinger, D.C. (2012). A strategy for comparing the contributions of environmental chemicals and other risk factors to neurodevelopment of children. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(4), 501-507. Bickley, L.S. (2002). Bates guide to physical assessment and history taking (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Drell, D., & Adamson, A. (2003). Fast forward to 2020: What to expect in molecular medicine. Human Genome Project Information. Retrieved June 30, 2012 from http://www.ornl.gov/ sci/techresources/Human_Genome/medicine/tnty.shtml Eggenberger, S., Krumwiede, N., Meiers, S., Christian, A., & VanGelderen, S. (2013). Godinho, M.F.E., Sieuwerts, A. M., Look, M.P., Meijer, D., Foekens, J.A., Dorssers, L.C.J., & van Agthoven, T. (2012). Relevance of BCAR4 in tamoxifen resistance and tumor aggressiveness of human breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 103, 12841291. Jensen, S. (2011). Nursing health assessment: A best practice approach. Philadelphia, PA: Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell 14 Wolters Kulwer Health / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Knafl, K., Breitmayer, B., Gallo, A., & Zoeller, L. (1996). Family response to childhood chronic illness: Description of management styles. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 11(5), 315-326. Doi:10.1016/S0882-5963(05)80655-X Krumwiede, N., Meiers, S., Bliesmer, J., Eggenberger, S., Earle, P., Murray, S., Harman, G., Andros, D., & Rydholm, K. (2004). Turbulent waiting with intensified connection: The family experience of neutropenia. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(6), 1-8. National Center for Biotechnology Information (2011). The International HAPMAP Project. Retrieved June 21, 2012 from http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov./ Neuman, B., & Fawcett, J. (Eds.) (2011). The Neuman systems model (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Potter, P. A., Perry, A.G., Stockert, P., & Hall, A. (2012). Fundamentals of nursing (8th Edition). Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Inc. Roy, S. C. (2009). The Roy Adaptation Model (3rd Ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Tanner, C.A. (2006). Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(6), 204-211. The International HAPMAP 3 Consortium. (2010). Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature, 467(7311), 52-58. U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research. (2012). Human genome project information. Retrieved June 30, 2012 from http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/home.shtml. Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 Family-Focused Nursing Care: ‘Think Family’ and Transform Nursing Practice Denham, Eggenberger, Young, & Krumwiede Instructor Guide: Chapter #5 Meiers, Krumwiede, Denham, & Bell Wright, L., & Leahy, M. (2009). The Calgary Family Intervention Model. In L. Wright & M. Leahy (Eds.), Nurses and families: A guide to family assessment and intervention (pp. 143-167). Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Family-Focused Nursing Care ©2015 15