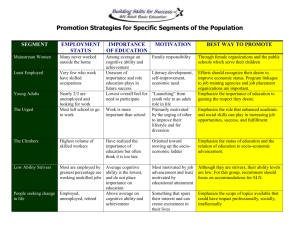

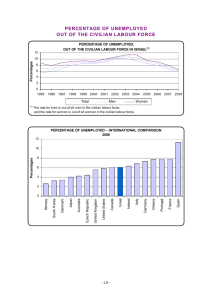

Perceived employment situation of Best Agers

advertisement