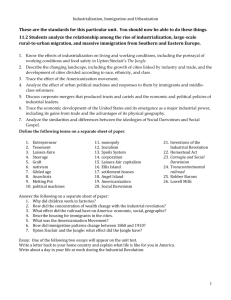

Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic

advertisement