A Worker-by - Washington and Lee University School of Law

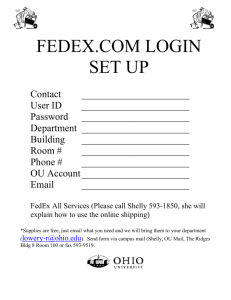

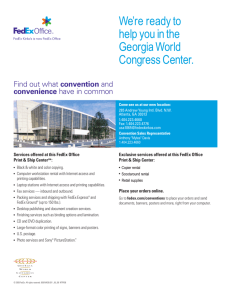

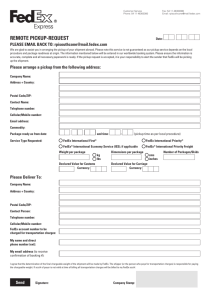

advertisement