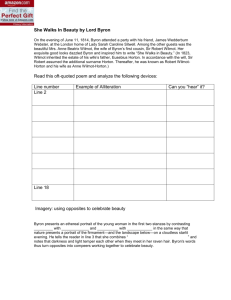

A Discourse on Byron's Don Juan

advertisement

黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 九國九十四年 WHAMPOA - An Interdisciplinary Journal 49(2005) 287-308 287 A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan Hwong Chang Liou Lishu Chang Chien Department of Foreign Languages, Chinese Military Academy, Taiwan Abstract This paper aims to defend for the morality of Byron’s poetry. Some critics and discourses assert that Byron is immoral for his hero’s lewd personality and prodigal wandering. Based on the theory of Romantic poetry, I will analyze the long poem Don Juan and scrutinize the relations among education, sex/race, love marriage, ethics, and morality in the poetic narrative. In this poem Byron represents Don Juan’s quest for the pre-lapsarian Eden in the natural world. This paper concludes that Byron is a moral poet who reiterates the significance of the borderless love and he expands his concerns for the symbiosis between humans and nature. Keywords: Byronic hero, the psychological and social contexts, morality, pre-lapsarian Eden, symbiosis Byron was the most diversified one of the English Romantic poets, for he experimented Don Juan--“an especial and exquisite balance and sustenance of alternate tones” (375). In with everything in poetry and in life: at four-and-twenty, he wrote, he had taken his “degrees in most dissipation"1 (B’s L&J. IX, 22). For many of his contemporaries in England, spite of this mixed perspectives Byron was a traditionalist in language and style, preferring the common forms of couplet and Spenserian stanza, and having no interest in the stylistic Europe, and America, Byron was the embodiment of the Romantic spirit, both in his poetry and in his personal life. Proud, passionate, rebellious, deeply marked by painful and often mysterious experiences in the past, yet fiercely and defiantly committed to following innovations proposed by Coleridge and Wordsworth. Byron's poetry is fundamentally Romantic, partly because in his very difference from the others he is asserting his individuality, and partly because of his subject-matter. He asserts, “ The highest of his own individual destiny--this was the image that Byron created for his contemporaries and passed on to subsequent ages. all poetry is ethical poetry, as the highest of all earthly objects must be moral truth” (L. J. V, 554). Yet his characters, including himself, Many of his poems are a curious blend of romantic melancholy and satiric irony. Byron is concerned with fame, a subject to which he will often return, especially in Don are significantly out-of-ordinary: Childe Harold, the restless, lonely wanderer; the heroes of the tale, courageous, glamorous, and mysterious; figures of guilt and unspecified Juan. Charles Swinburne shrewdly singled out as the hallmark of Byron's greatest work, sorrow, such as Manfred. They are unusual, deeply sensitive, brooding on the past, and 288 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 above all they are outside the normal simplicities of thinking and feeling, beyond the anesthetizing confines of society. The dark and brooding nature of Childe Harold is indoctrination and the liberty of peoples--with the familiar Byronic Hero qualities of misanthropy, solitariness, and pride” (Trueblood 83). However, what essential to Byron's definition of heroism, for it is his intense and dramatic inner life that sets the Byronic hero apart from, and above, the common herd. In Childe Harold’s Byron can claim is still that proud independence and the fineness of his sensibility by which he makes a retreat from the world. Jerome J. McGann says, “The Pilgrimage as well as in Don Juan, Byron creates the figure known as the “Byronic hero”: a passionate, moody, restless character who has exhausted most of the world's action of the artist reveals this permanent truth by imaging the sublime and 'Ideal' forms which represent men's passionate efforts not simply to endure, but to prevail” excitements, and who lives under the weight of some mysterious sin committed in the past. His defiant individualism refuses to be limited (129). The poet’s historical imagination produces a continual interplay between the past and the present in this way, and his by the norms of institutional and moral strictures of society. He is an "outsider" whose daring life both isolates him and makes him attractive. sense of place interacts with his self-consciousness, so that there is a complex mixture in the reflection, remembrance, hope, and melancholy, all The Byronic hero is deeply an ambivalent figure, both damned and blessed by virtue. Andrew Rutherford sees this as inspired by the landscape itself. The plot of Don Juan is indeed highlighted by Juan's six major adventures. part of the contradiction in Byron's own character: the Childe is a projection of his melancholy and disillusioned side, while “the narrator mirrors his more normal and His involvement with Donna Julia, a married friend of his mother, which leads to his hasty departure from Spain; his life at sea, his shipwreck, and his ordeal in an open attractive personality” (A Critical Study, 267). Byron always seeks to escape from the human society because he has closely viewed the hardest reality for the Romantic to bear: the imperfection of human nature. Being conscious of his wrongs and sorrows boat; his involvement with Haidee, the daughter of a Greek pirate, which causes him to be sold into slavery; his adventures as a slave in Constantinople and his efforts to avoid the advances of the Sultan's favorite wife, Gulbeyaz; his escape to Russia and his and his own innate superiority, Byron flies to solitude among the mountains, where he looks on the vastness of great nature. He exploits in the Russian Army, which brings him to the attention of the Empress Catherine II; and his mission to England as desires to be alone that he may “love Earth only for its earthly sake” (Childe Harold III.71). Byron might want to “combine ‘romantic liberalism’,-revolutionary the representative of Catherine, his acceptance in London society, and his usual amatory difficult. In spite of the record of the six major entanglements in the life of its Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 289 titular hero, Don Juan is basically a mock-epic that fuses with picaresque romance, for the adventures in the poem are all amorous. epics; both are rhymed and epigrammatic; both are satires; both are in iambic pentameter; and both deal with human folly. Byron explains that Don Juan is not only a mock epic in the Don Juan does not progress in a straight line but meanders in many directions. Again and again, Byron departs from his story to comment on politics, style of Pope but also a boisterous satire mocking the whole cultural scene. Bloom states that the poem became “a satire of European Man and Society which attempts epic relations between men and women, other poets, and the social vices, follies, and absurdities of his time. In the third canto, Byron apologizes for his digressions from dimensions” (The Visionary Company 258). While making fun of others, he also makes fun of himself. Byron's purpose was to describe the world as he saw them, even if this view the main thread of his story. In the shipwreck incident, for example, the pitiful condition of the survivors whose sufferings caused outrage among his critics. In Canto XII, he states both his purpose and his prognosis: I mean to show things really as they are, drive them to draw lots and eat one another is vividly described. Four stanzas (II. 87-90) are devoted to the experience of two fathers helplessly watching their sons die; Not as they ought to be: for I vow That till we see what's what in face, we're far From much improvement. (D. J. XII. 40) Byron is here, of course, attacking a the horror of cannibalism is recognized and the subsequent symptoms of madness in the cannibals are presented in frightful detail. conception of morality that would equate it with keeping things nice and clear; his stanza goes on to propose a far more But Byron intends to involve the sympathies of his readers in affecting and sometimes terrible events and then joke at their expense. “A deliberate rambling digresiveness,” effective morality, one which is aware of the truth and starts from there. Byron decided that he must tell the truth in the hope of improving mankind. Northrop Frye observes, “is endemic in the narrative technique of satire, and so is a calculated bathos or art of sinking its suspense” (216). Most admirers of Don Juan agree that without the digressions, it would be a far inferior poem. The He was not surprised that Don Juan shocked a large number of people, but he held that he himself was not to blame. He declares in the letter to Murray: “I maintain that it is the most moral of poems; but if people won't discover the moral, that is their fault, not looseness of structure allows Byron to make innumerable digressions in order to divulge his own personal views of love, politics, or mine” (“To Murray” February 1st, 1819; L. & J. VI. 99). This is typical of the method behind Don Juan; it claims to have society and his scorn for most of the eminent poets of his day. Don Juan is often compared with Pope's The Rape of the Lock. Both poems are mock skepticism on the surface, but then reveals its own superior feeling. The intricate relationship between its carefree surface and its deeper sensitivity is one of the major 290 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 virtues of Don Juan. Byron's purpose was to expose the hypocrisy and the corruption of the high society which he knew so well. In order to “show things really as they,” however, for at the same time he offers a knowing on the events he describes. At times he underscores his sophisticated outlook by directly punctuating the action with Byron needs a hero: I want a hero: an uncommon want, When every year and month sends forth a new one, Till, after cloying the gazettes with cant, pungent asides. For example, Byron ends a stanza describing Juan's moody meditations after meeting Donna Julia with an earthy, realistic judgment on his “longings sublime, The age discovers he is not the true one: Of such as these I should not care to vaunt, I'll therefore take our ancient friend Don Juan—We all have seen him, in the and aspirations high”(I. 93). Another mask of the persona is a comic version of the Byronic hero, the melancholy romantic man of feeling. Toward the end of pantomime, Sent to the Devil somewhat ere his time. (D. J. I. 1) Byron himself makes his presence felt in Don Canto I, he parodies romantic emotion, lamenting his lost youth and saying adieu to affairs of the heart. Taking up the “good Juan primarily through the voice of the narrator, who appears to be making up his poem as he goes along and who recounts the adventures of Don Juan, a younger version of himself, with a splendid old-gentlemanly vice of avarice, he satires the world-weariness of Childe Harold. At the beginning of Canto IV, he emphasizes an adult perspective which transforms melancholy balance of satire and sympathy. Despite the narrator's opening lament, “I want a hero”(I.1), Byron is in a sense the cynicism into comic satire: “And the sad truth which hovers o'er my dest / Turns what was once romantic to burlesque” (IV. 3). hero of his own epic. The “I” of persona constantly intrudes on the story he is telling; his views, problems, quirks, and preferences create an ongoing autobiography which Throughout the poem, we are aware of the narrator as a writer, endlessly embroiled in the act of composition. As a writer, the narrator often pretends overshadows Don Juan's adventures. This persona wears a series of different masks as Watson illustrates, “The persona is a part of his shifting self, of his endless exploration of life, of his continual search for something that would occupy his energy"(261). For to be a bumbling novice not in full control of his materials. I don't pretend that I quite understand My own meaning when I would be very fine; But the fact is that I have nothing planned, Unless it were to be a moment merry, instance, in the opening canto, he displays himself as a fussy, avuncular bachelor, interfering in the domestic affairs of Donna A novel word in my vocabulary. (IV. 5) Inez and Don Jose and informing the audience of his personal opinions on education, literature, women, the law, and other topics. His bumbling naiveté is only a pretense, plan “to be a moment merry” is the artful strategy of an expert satirist who pokes fun at various targets while appearing to be nothing more than an idle bystander seeking Beneath the surface, however, his Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 291 innocent amusement. Thus in a passage on the meaning of life, the narrator's pretended befuddlement serves as a means of satirizing abstract philosophy and bringing the reader Donna Inez. At just twenty-three Julia married to a man of fifty, but she determines “that a virtuous woman / should rather face and overcome temptation” (I. 77). Byron back to the realm of practical judgment, all in the spirit of a genial game: Few mortals know what end they would be at, But whether Glory, Power, or Love, or shows his understanding and sympathy for the instinctive feelings of the young wife and old husband, though he mercilessly mocks at the self-deceiving Platonism of Treasure, The path is through perplexing ways, and when The goal is gain’d, we die, you know--and then-- (I. 133) What then? -- I do not know, no more do Julia. To say Julia falls in the charm of the situation is not quite the same as saying that she is seduced by a state of mind entailing sexual intimacy. Over Julia and Juan’s first you—And so good night.--Return we to our story: (I. 134) The ultimate effect of the narrator's embrace the narrator pauses, “God knows what next--I can't go on” (I. 115), and the halt responds to obstacles both moral and voice is to provide a comic sense of distance which contributes to the success of the satire and to help create a discrepancy between the heroic ideals of conventional epic and the imaginative, waiting for Julia’s “I will ne'er consent” (I.117). And she soon will. For Julia her seduction moves from charm to consent, depends on a physical touch that down-to-earth realism of Don Juan. In “Seville” Juan was born (I. 8), his father Jose a "true Hidalgo", and his mother can't be resisted biologically and spiritually. Here Platonic doctrine enables Julia's frankly sensual impulses to impel her to Inez, a “learned lady.” Juan's parents lived “an unhappy sort of life, / wishing each other, not divorced but dead” (I. 24). Byron drew on his own marriage in painting consent. The power of charm propels her to a nondiscursive consent. According to Jerome Christensen, “Julia is a mixture of impulses and her blood a mixture of class, the quarrels between Inez and Don Jose, and details like Inez’s spiteful attempt to prove her loving lord was mad” just as lady Byron had done. After Don Jose dies, Juan becomes an orphan living with his “perfect” mother. The lack of affection in Inez's life the essentializing of her as woman is complicated and constantly under adjustment in the canto; yet even disregarding those complications, the essentialized, biologically burdened feminine cannot be strictly identified with produces a corresponding fixation with Juan. The overly protective mother resolves at all costs to make Juan quite “a paragon” (I. 54). the aristocracy; she is but one component of the aristocratic complex that the poem projects” (224). At sixteen, Don Juan was a handsome lad much admired by his mother's friends. Among the numerous acquaintances all, Julia was quite a favorite friend of The love story portrays Don Juan's first sexual encounter in terms of bedroom farce, with the cuckolded husband discovering the lovers after a series of comic 292 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 mishaps. Despite the elements of mockery and farce which enliven the episode, Byron puts into Julia’s passion his ideal of what a thing should be. Her husband means the tenets of modern Ecocriticism that man is not the dominator of nature. The shipwreck proves two facts. One of them is that the heavy industry cannot promise the nothing to her, and she pines both to give and to receive affection. The narrator retains sympathy for Julia by depicting her as the victim of her passions and incapable security of man’s exploration in the natural world. The second, “the masculine quest for world domination” is dangerous (McKusick 197). of preventing the hypocrisy she practices since “passion most dissembles” (I. 73), but similes he employs implicate her in a world much more ambiguous than Juan’s. As Like Inez's resolution to cultivate Juan as a paragon goes awry, Julia's letter realizes the nightmare of uncertainty in the shipwreck cannibalism. Pedrillo is killed Bowra says, “Julia has staked everything on an act which she feels to be wrong and yet desires with all her being, and in the end she so that the crew may survive. Pedrillo’s passing marks the end of the outward constraints Inez exerts on Juan. Juan fails”( 167). As soon as Julia’s husband, Don alfonso, discovers their affair, Juan is sent away by his mother and begins a tour of rejects the cannibal feast then survives the tragedy because he follows Byron's aphorism in “Detached Thoughts” that “Man is born passionate of body but with an innate Europe. Juan has been sent to “Cadiz” (II. 5) to board the ship Trinidada bound for though secret tendency to the love of Good Leghorn, Italy. He has to undergo the cyclic pattern of aspiration and descent and taste the bitter fruit of fall. His “first and passionate love” (I. 127) results in being shipwreck, reaches shore, a new Adam, freshly baptized by the waves, to find before a new Eve, Haidee. In Lambro's absense, Juan and Haidee fall in love, and believing exiled from his hometown as man's “first disobedience” of Adam from the paradise. Juan's seasick on the voyage symbolizes the circumstantial hardship and natural limitations imposed on man. And the shipwreck embodies the traps and turmoil on her father to be dead, settle down together in domestic bliss. The idyll of Juan and Haidee in Cantos II and III is the least complicated in its assertiveness. Byron compares the young lovers to Adam and Eve before fall: man's pilgrimage from the earth to heaven. The story of the shipwreck and its aftermath shows us that “nature might at any moment Alas! for Juan and Haidee! they were So loving and so lovely -- till then never, Excepting our first parents, such a pair betray the heart that loves her, shows us the incapable power of what he elsewhere called ‘circumstance, that unspiritual god’” (McCalman 276). The episode also heralds Had run the risk of being damned for ever. ..(II. 193) Juan and Haidee meet apart from their respective societies; they cannot speak in his Mainspring of Mind” ( L.& J. V, 457). Juan, the only survivor of the Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 293 one another's languages. Byron implies, and might be a general experience if it were not interfered with by social conventions. Haidee is a child of nature in the sense that The true Romantic did hate inconstancy, it was the negation of his ideal love and evidence of a human frailty that was intolerable to the romantic idealist. In she has not been corrupted by society but follows her instincts without questioning their worth or their consequences. She presents an implicit contrast to the young fact, we find Juan twice resisting sexual temptation because of his memories of Julia. The narrator's voice is a unifying force which places events, interpreting what each aristocratic English women who pursued Byron when he was in fashion. But Byron's enthusiasm does not prevent him from indulging in occasional ironic sides reveals about love. But the Haidee story is somewhat different despite the continuing presence of the satiric persona. Indeed the whole love idyll is given in the setting of even in this section of the poem; they are designed to qualify sentimental falsifications of love. Haidee seems innocence actual conditions. It should be so because the passionate love of Juan and Haidee is not an illusion based on social or literary personified, but for Byron no person is innocent. Just as the hero's recurrent scrapes with women provide a unified thread conventions, but a beautiful experience. Since their love escapes from the trap of hypocrisy, self-deception, or mercenary motives, it is presented as an ideal and throughout, so the narrator's ongoing discussion of love, sex, and marriage lends the disparate incidents thematic coherence. perfect even without any wedding ceremony. Byron's observations on love and marriage, however, are presented as a contrast with the J. W. Smeed regards the love affair between Juan and Haidee as “no thoughtless and callous seduction; Byron treats the whole episode (which ends in tragedy for Haidee) idyllic natural marriage of Juan and Haidee. We also feel the pathos in their love of beauty and passion that will lead to damnation if the external powers of social seriously and sympathetically and makes clear that the young couple are genuinely in love”(37). However, the narrator asks, "But Juan! had he quite forgotten Julia? / And should he have forgotten her so soon? (II. 208). For the complex question, norms are to be claimed. Leslie A. Marchand observes, “this ideal and innocent love had the seeds of its own destruction inherent in it” (182). The isolated Aegean island, far outside society, in the context of Nature and Andrew Rutheford suggests, “Juan's terrible experiences in the shipwreck serve to obliterate from his mind and from ours the solitude, provides Juan and Haidee ephemeral enjoyment. Rumor has it that Haidee's father has died on a piratical memory of Julia--it is almost as if he had died and been reborn--so that we see no infidelity, no promiscuity, in his loving Haidee” (154). expedition. The news throws the newly couple into several weeks of mourning. After that, Haidee and Juan move into his home as man and wife, and entertain 294 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 lavishly. Thus Lambro's sudden homecoming forces Haidee to encounter a dilemma which results from the conflict between her father and spouse. The intention to present “this poem” as “a moral model”(V. 2). The consciousness of human mortality is found throughout Don Juan: human life is frail, a brief existence against awkward situation of family affair is then compared to a national event by the minstrel's song, “The Isles of Greece” lamenting for Greece's present state of the background of the passing of ages. What should be valued in this life is love, and heroism; but both are ultimately subject to time. The beautiful becomes Oneness subjection to Turkey and telling Haidee's lose of her mother country over love. Nigel Wood notes, “The “Isles of Greece” hymn uttered by the poet in Canto III has with the wicked, the hypocritical, and the ridiculous in death. Love and beauty are signs of a human nature that has escaped the usual corruption. provoked a suggestive study by Jerome J. McGann which takes issue with formalist analyses of literature. . . . The poetry In a fallen world, a figure like Haidee is a reminder of the days before fall in the Garden of Eden. It may be for this becomes, “an act of social consciousness which can only be carried out in words but which cannot be defined in them” (The Beauty of Inflection 157). reason, because they stand apart from all the cruelty, pretense, and hypocrisy of life, that Byron was excited by beautiful women and able to thrill the reader by describing them. Out of anger and jealousy, Lambro tears the newly couple apart at the cost of Haidee's life and her baby. Haidee's death Haidee, for example, died giving birth to Juan's child but he would never know this because he was put aboard a slave ship is a far more wrenching and tragic conclusion than Donna Julia's confinement in a convent, and the tone at the end of Canto IV is somber and austere. When all bound for a distant market. Byron then paves the path for the scenes in the seraglio as he describes the slave market in a “raw day of Autumn's bleak beginning”(V. 6). is over, with Juan wounded and sold into slavery, and Haidee died of a romantically broken heart, Byron gives us his most deliberate stanza of moral confusion. Byron heightens the effect of tragedy by focusing on Haidee's unborn child who died Byron doesn't propose for slave purchase. Instead, Byron comments on the merchant who enjoys his hearty dinner at the cost of his fellow beings. He voices his own revulsion against being a slave to any physical appetite. with her. Some earlier critics declared that Don Juan was neither moral nor immoral, Juan acquiesces when Baba, the eunuch orders him to disguise himself as a girl. He comes to the encounter with that it was written to amuse, to shock, to horrify and startle, to make the serious absurd, and to play tricks with our feelings. Yet Byron in Canto V announces his Gulbeyaz, the sultana who had ordered Juan purchased for her pleasure. Gulbeyaz's ultimate purpose for buying Juan is exposed in the chamber where she supposed he Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 295 would satisfy her craving for love as well as carnal desire. Gulbeyaz seldom has the chance to meet her husband. The empty chamber works nothing but a prison to so of Haidee, his ephemeral time of happiness. They feel sympathetic for each other because misfortune of one kind or another is the common lot for all people. beautiful a do is buy a satisfy her frustration. woman. What she attempts to “man” to console her loneliness, need of love, and relieve her The point is that neither men Byron here attacks at polygamy by presenting Gulbeyaz's troubled married life. Her marriage, like Donna Julia's, is to a man much older than herself, with “fifty nor girls should be bought for sexual slavery, which might explain the reason why Juan resists such temptation. Love is only for the “free!” as he declares (V. 127). Juan “is daughters and four dozen sons,” and three other wives and 1500 concubines (VI.152). To the disparity of his age may be added his necessary neglect of her. At the advanced indeed ‘free’ of the power of Gulbeyaz's world . . . , for Juan is a certain sort of person--a young, fairly volatile man with age of twenty-six, the inhabitant of a Moslem harem has none of Donna Julia's hesitancies or inhibitions. fairly undeveloped powers of comprehension--so his 'freedom' of behavior is partly the result of his innocence (and ignorance)” (Don Juan in Context114). In Gulbeyaz appears more self-possessed than Donna Julia and has the charm of her passion's intensity, but her love is a form of imperial, or imperious, bondage. Don Juan, innocence is highly valued, particularly in relation to certain kinds of adult behavior. Explicitly, Byron declares She illustrates a theory propounded in Canto III: “In her first passion Woman loves her lover, / In all the others all she loves is love” his intention that the canto is for “merry,” actually, Byron presents a serious problem of human relationship to the reader, and calls for mutual respect for men and women. (III.3). This epigram offers a generalization about human nature and constitutes a neat maxim on feminine psychology. Epigrams are frequent All seems in vain for Gulbeyaz's attempt to seduce or force Juan to “love” her because Juan's inner has been occupied by his innocent “wife,” Haidee. In his eye, Gulbeyaz finds no flame of love and wonders, “Christian, canst thou love?” (V. throughout the poem; in fact, there is one in the final couplet at the end of every stanza. Byron uses vivid imagery or wise generalizations in pointed phrases which temporarily halt the narrative flow. Many of the epigrams have the quality of brief 116). Gulbeyaz throws herself on to Juan's breast seeking his love but Juan shows no sign of love. Juan’s rejection of definitions, such as the following: What men call gallantry, and gods adultery, Is much more common where the climate's Gulbeyaz’s embrace humiliates her and makes her bursts into tears, too. The tears in the chamber wash away their hatred. Juan's tears has flowed over the misfortune sultry. (I. 63) For instance – passion in a lover is glorious, But in a husband is pronounced uxorious. (III. 6) 296 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 Epigram is one of the rhetorical devices in Don Juan that often serves to expose the absurdity of human vices and follies. By this means, Byron unmasks hypocrisy and and civilians were sacrificed for the whims and ambitions of their rulers and military commanders. He insists on the wrongs and futility of fighting for any cause but that of pretense. Juan is indeed unable to love Gulbeyaz, for he still yearns for Haidee. And when it emerges the following morning that after Liberty, he emphasizes the waste, suffering, and cruelty of war--the essential inhumanity of the the whole business. These ideas are much the same as those expressed in the failing Gulbeyaz, he has spent the night with one of the concubines, Gulbeyaz orders that both of them be immediately put to death. Fortunately, Don Juan escapes from the third canto of Childe Harold. Now, however, they are presented with new power and cogency, which come from Byron's changed techniques and from a different palace of the sultana soon after Gulbeyaz orders him to death and joins the army of Catherine of Russia that is at war with the quality in his poetic thinking. The principal example of this is the description of the siege of Ismail. Byron's eye for sultan. In Cantos VII and VIII Byron describes the Battle of Ismail between Russia and Turkey(VII. 9). However, in the first seven stanzas of Canto VII Byron detail is its guarantee of truth and seriousness: this is no long-distance view of war, but a close-up description which makes it look very different from the glory defends himself against those critics of Don Juan who accuse the poet of “tendency to under-rate and scoff / At human power and assumed by much patriotic verse. It begins with an artillery barrage, which is indiscriminate in its effect and kills soldiers virtue”(VII. 3). In “holding up nothingness of life” (VII. 6), he argues that all things are merely a show. Then Byron moves to a new and fresh subject in which his strong and civilians alike; it progresses through each stage of the conflict, so that the reader is made to face the infinities of agony Which meet the gaze, whate'er it may feelings about war are immediately revealed. Byron's sympathies are neither with the Russians, who are as interested in material gain as in defeating the infidel, nor with the Turks, but with those who are to be killed or wounded in the attack, and his scorn is for regard—The groan, the roll in dust, the all--white eye Turn'd back within its socket-(VIII. 13) Byron enforces his moral judgments by showing war as it really is--by giving his readers a vivid and detailed account of an actual all who confuse glory with bloodshed. Wars to Byron “Except in Freedom's battles / Are nothing but a child of murder's campaign--by painting, in his own words, “the true portrait of one battle-field” (P.W. VI. 334). The poet is concerned with individual rattles” (VIII.4). He just supports battles for freedom where people are fighting against tyranny and for human right. He hates wars of conquest wherein the soldiers human beings, and attacks worldly “Glory.” He claims that this great desideratum is a mere illusion, since most “heroes” are unknown or soon forgotten. To Byron Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 297 heroes are too often simply “butchers in large business,” and glory is won by those who murder their fellow-men. It is of no value to the soldiers who are killed, or to Byron attacks not only commanders, but the civilians who accept it so uncritically. Although he is attacking the cant of glory he does not fall into the easy trap of sneering most of those who survive. Byron has an eye for the absurd as well as for the horrible: Thrice happy he whose name has been well spelt. In the despatch: I knew a man indiscriminately at soldiers and the military virtues--he recognizes that in battle men can show great courage, and he gives them credit for it: whose loss. Was painted Grove, although his name was Grose. (VIII.18) The tone of equanimity with which Byron describes some of the siege must not The troops, already disembark'd, push'd on To take a battery on the right: the others, Who landed lower down, their landing done, Had set to work as briskly as their be mistaken for callousness. He is quite capable of arousing the reader's pity and fear when he needs to, as he does when two brothers: Being grenadiers, they mounted one by one, Cheerful as children climb the breasts of mothers, O'er the intrenchment Cossacks attempt to kill a little girl of ten who is rescued by Juan. For much of the time, however, the dead-pan tone is unpleasantly grim, almost and the palisade, Quite orderly, as if upon parade. And this was admirable. . . . (VIII. 15-16) The concession does not weaken his as if the poet is holding the reader's head and forcing him to look. The whole episode becomes a fearful indictment of the state of indictment of war, but reinforces it by making us sense the fairness and honesty of his procedure. “Apart from the obvious society: this is the point made by the lyrical digression on Daniel Boone, after which we are pulled back to the horror of war with redoubled effect: moral passion in many passages,” writes Helen Gardner, “we are in no doubt as we read that Byron admires courage, generosity, compassion and honesty, and that he dislikes So much for Nature: – by way of variety, Now back to the great joys, Civilisation! And the sweet consequence of large society, War – pestilence – the despot’s desolation (VIII. 68). The theme of war merges inevitably brutality, meanness, and above all self-importance, hypocrisy and priggery"(310). In his whole treatment of the siege, Byron thus shows his intense and indefatigable interest in the reality, and his consequent desire to give an accurate into the theme of tyranny which, in Byron’s view, is inseparable from war and, in fact, is its primary cause. Heartless despots who truthful picture of human life. By embroiling Juan in the Russo-Turkish War, Byron is able, both by story and commentary, to rejoice in conquest and carnage, such as Catherine of Russia and Napoleon the liberator turned conqueror, are the objects of Byron’s forthright attack. denounce the savagery, abysmal inhumanity, folly, and utter futility of war. In the battle field, Juan turns out to be such a valiant soldier that he is sent to St. Petersburg, to 298 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 carry the news of a Russian victory to Empress Catherine who also casts longing eyes on the handsome stranger, and her approval soon makes Don Juan the toast of [Byron] can see with ironic yet poignant regret the dissipation of the romantic dream of Childe Harold--Manfred, the dream of escaping the flesh by some transcendent leap into the her capital. Juan's feeling for the middle-aged empress, however, are based rather on his own vanity than upon her beauty: freedom of a world of spirit (Byron’s Poetry 212). Don Juan has “gone out on Shooter's Hill” (XI, 8) where he is “wrapt in contemplation” on the ideal life in Britain. Her sweet smile, and her then majestic figure, Her plumpness, her imperial condescension, Her preference of a boy to men much bigger (Fellows whom Messalina's self would pension), Walking behind his carriage, o'er the summit, he is interrupted by a knife, with—“damn your eyes! your money or your life!” (XI. 10). Juan who understands no English but “God Her prime of life, just now in juicy vigour, With other extras, which we need not mention, – All these, or any one of these, explain damn” quickly senses their gesture (XI. 12). He draws forth a pocket-pistol and fires it into one assailant's pudding. He then wishes “he Enough to make a stripling very vain. (IX. 72) In Russia Juan becomes a polished Russian courtier and in the process also becomes a little dissipated. He lives “in a had been less hasty with his flint” (XI. 14) and thinks “it is the country's wont / To welcome foreigners in this way” (XI. 15). Byron's purpose in having Juan being hurry / Of waste, and haste, and glare, and gloss, and glitter” (X. 26). But the physical environment in Russia does not continue to robbed while in meditation may be to present the conflict between the idealized and realistic world. The robbery destroys Juan’s dream of agree with Juan, and consequently he falls sick. The physicians, unable to determine the exact cause of his illness, recommend a change of climate. It happens that at the the brave new world. But he still tries his best to help the robber, Tom, to his feet, then travels to the “capital apace” (XI. 18). His chariot passes through “Groves” devoid of trees, and time the Empress Catherine is involved in negotiations with the English, and she decides to send him on a mission to England. Juan is well received in London for he is a polished young man now, well versed in “Mount Pleasant” (XI. 21). Juan encounters the sparkling vision of Westminster, the grand Abbey, the "line of lights” up to Charng Cross and golden Pall Mall (XI. 24, 25, 26). The scenery surges up to fill Byron's mind with nostalgic memories. With his diplomatic fashionable etiquette. Juan ends the canto with the promise of telling his fellow countrymen some unpleasant truths about mission, Juan soon comes into contact with politicians. He finds himself “extremely in the fashion” especially for those numerous themselves which, he says, they will not believe. Then Juan's voyage comes to its climax in the English cantos (XI-XVII). Leslie A. Marchand points out, "Now he English women who have heard the rumors about his adventures in “wars and loves” (XI .33). Juan is annoyed by those politicians who “live by lies, yet dare not boldly lie” (XI. Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 299 36). He mocks himself that “Now, what I love in women is, they won't / Or can't do otherwise the lie”(XI. 36). He despises evil things disguised as goodness. A true coherence of seem to enjoy social life because of the sympathy he feels for poor men of his age, overwhelmed by the pressure of making a living. He thinks he is “Too old for mind and action should be the moral model for Byron himself. Of course, he expects his countrymen to search for the “truth” instead of “the truth in masquerade” (XI. 37). Youth,--too young, at thirty-five” To herd with boys, or hoard with good threescore, – I wonder people should be left alive; Juan spends his mornings in business, “a laborious nothing” (XI. 55), his afternoons “in visits, luncheons, / Lounging and boxing and the twilight hour / In riding But since they are, that epoch is a bore: Love lingers still, although 'twere late to wive: And as for other love, the illusion's o'er; And Money, that most pure imagination, round those vegetable puncheons / Called 'parks,' where there is neither fruit nor flowers” (XI. 56). Fast flashing chariots Gleams only through the dawn of its creation. ( XII. 2) Now that the “illusion” of romantic hurl “like harness'd meteros” to the doors opening onto “An earthy paradise of Or Molu” (XI. 57). The buzz of these activities produces “nothing” but consumes love is no longer possible, the only goal that seems to lie ahead is money and the making of money--money being as specifically associated with age and experience as their resources, energy, and time. To Byron, it is the very picture of Vanity Fair. It is the fashionable world that Byron criticizes. romantic love has been with youth and innocence. Money rules the world and even rules love: Byron then gives Juan some advice for dealing with his English society: But "carpe diem," Juan. . . And above all keep a sharp eye “Love rules the Camp, the Court, the Grove,--for Love Is Heaven, and Heaven is Love:”--so sings the bard; Much less on what you do than what you say; Be hypocritical, be cautious, be Not what you seem, but always what you see. (XI. 86) "Carpe diem" is a prescription for all occasions. The citation attempts to Which it were rather difficult to prove (A thing with poetry in general hard). Perhaps there may be something in "the grove,"At least it rhymes to "Love: " but I'm prepared To doubt (No less than landlords of their generate for the maxim a normative transcendence of the moment of audition. To be failed or successful depends on the rental)” If "Courts" and "Camps" be quite so sentimental. (XII. 13) occasion of seizing the hour, the day, the language, the purse, the monastery the monk, or “the last word” (XIII. 98). Though middle-aged, Juan doesn't But if Love don't, Cash does, and Cash alone:Cash rules the Grove, and fells it too besides;Without cash, camps were thin, 300 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 and courts were none;Without cash, Malthus tells you – "Take no brides."So Cash rules Love the ruler, on his ownHigh ground, as virgin Cynthia sways the tides. From much improvement with that virtuous plough Which skims the surface, leaving scarce a scar Upon the black loam long manured by Vice, (XII. 14) Money is not romantic, perhaps--but in a sense it is. If love is an illusion, money in some cases is very real. Only to keep its corn at the old price. (XII. 40) It seems all these characteristics contradict each other, but they are all true. The English cantos are a litany for an eighteenth-century world, forever lost, and by Byron forever lamented. Harold Bloom writes, “The age of reason and love is over, The poem is facetious, and giggle-making, and moral, all at once. We may not agree with the poet on some of his observations, but we can still admire his willingness to the poet insists, and the age of Cash has begun. The poem has seen sex displaced into war, and now sees both as displaced defy the world and its convention. J R. de. J. Jackson says, “In Canto XII he can turn the outcry against his immorality to good into money. Money and coldness dominate England, hypocritically masked as the morality that exiled Byron and now condemns his epic” (270). Through Juan’s account by threatening to resume it and immediately associating the world with truthfulness in such a way as to embarrass his critics’ (176). The episodic quality of points of view, London is a place “Where every kind of mischief's daily brewing” (XII. 23). When tired of play, he flirted “without the poem permits digression and the later declaration of Byron's intention as he announces, “But now I will begin my sin / with some of those fair creatures who have prided / Themselves on innocent tantalization” (XII. 25). Byron told his friend Thomas Moore in poem. . . .These first twelve books are merely flourishes,/ Preludios” (XII. 54). From the very beginning of Canto XIII, Byron speaks in jest: “I now mean to be 1818 that his purpose in writing Don Juan meant “to be a little quietly facetious upon every thing” (The Works of Lord Byron: L & J. IV. 260). Later on October 12, 1820, he wrote Murray: “Don Juan will be known by and by, for what it intended,--a Satire on serious,-- this time, / Since Laughter now-a-day is deemed too serious,” and “I tell the tale as it is told"(XIII. 1, 8). But the progress of Don Juan is erratic and it is often subject to delays and interruptions. In fact, it was published in parts over a abuses of the present states of Society” ( The Works of Lord Byron: L & J. V. 97). In canto XII, Byron asserts, period of five years. Andrew Rutherford explains, “These were due partly to the influence of Byron's friends and his But now I'm going to be immoral; now I mean to show things really as they are, Not as they ought to be: for I avow, That till we see what's what in fact, we're far sensitivity to public opinion; for although he frequently asserted his indifference to such factors, it seems certain that he sometimes allowed them to divert him from his true Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 301 course” ( Byron: A Critical Study, 139). So far from planning the course of events, Byron admits, “the fact is that I have nothing planned”(IV.5). J. McGann Which makes the Southern Autumn’s day appear As if ‘twould to a second Spring resign The season rather than to Winter dear,Of in-door comforts still she hath a mine,- points out, “This pattern of unforeseen consequences operates throughout Don Juan--‘Few mortals know what end they would be at’ (I.133)--and it is based upon The sea-coal fires, the earliest of the year; Without doors, too, she may compete in mellow, As what is lost in green is gained in yellow. (XIII.77) His reference to the real change in the Byron's assessment of his own life as well as the general idea that too many factors impinge upon an event for anyone to be able to know at the time what it means, or where color of the leaves in autumn conveys an atmosphere peculiar to the English landscape at this time of year. Mario John Lupak says, “There may also be a hint of it will lead” ( Don Juan in Context 100). The episodic pattern often hints at the theme of “uncertainty.” Yet Byron shows the way nostalgia here for the one landscape he does not use in Juan’s journeys, his native Scotland” (191). of “full text” that “simultaneously gives the questions and the answers” (Derrida 473). “What's this to the purpose? you will say / Gent. reader, nothing; a mere speculation” Byron’s nostalgia is reflected in describing the place of his lost youth. The guests assembling at the Norman Abbey is a little display of foolery that has meaning in (XIV, 7). In play, there are two pleasures for your choosing--“The one is winning, and the other losing” (XIV. 12). In “This its madness. The activities at the country house party are nothing but pastimes. They gather to dine for “happiness for man--the paradise of pleasure and ennui,” Byron will show “Love, war, a tempest--surely there's variety,” and “A bird's eye-view, too, of that wild, Society" (XIV. 17, 14). hungry sinner! – / Since Eve ate apples, much depends on dinner” (XIII. 99). The older guests tumble books and criticize the pictures in the library (XIII. 103). The In English Cantos, Byron’s own memories and experiences of English society lays the foundations for the house party, to describe the Norman Abbey, to assemble the guests, and to present the way of living in English society. The ladies discuss fashion, settle bonnets, or write letters (XIII. 104). With evening come the banquet, the wine, and then the duet. Sometimes there is a dance, but not on field days, for the men are too tired. At Henry's Mansion the “Blank – Blank description of the Norman Abbey from “Druid oak,” and the “lucid lake” to the “remnant of the Gothic pile” reflects the Square” Juan is a wealthy guest. Diplomatic relations arising out of business bring Juan and Lord Henry “into close picture of Newstead Abbey (XIII.56. 57. 59). Don Juan’s visit to the mansion coincides with the shooting season: Then, if she hath not that serene decline contact” (XIII. 15). Henry’s wife, Lady Adeline Amundeville is “the most fatal Juan ever met” (XIII. 12). Her charms “made all men speak and women dumb” (XIII. 13). 302 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 Don Juan “A young unmarried man, with good name / and good fortune” is accepted again by the class of society to which he belongs by birth (XII. 58). “Born with that Aurora who is “a lovely being, scarcely formed or moulded” (XV. 43). For Byron that is probably her most salient and attractive quality. She views the world happy soul which seldom faints, / And mingling modestly in toils or sports,” he is cherished by women (XIV. 31). The three major female characters in with the silent awe of someone who has seen it all before: She looked as if she sat by Eden’s door And grieved for those who could return no these cantos are The Duchess of Fitz-Fulke, Adeline, and Aurora. The Duchess of Fitz-Fulke, a woman with imperious air of the past, reverberates with tones of more...She gazed upon a world she scarcely knew,As seeking not to know it, Silent, lone,As grows a flower, thus quietly she grew And kept heart serene within its Gulbeyaz and Catherine. Adeline reminds us of a slightly matured Julia in her innocence, beauty, sweet. At first, Adeline zone.There was awe in the homage which she drew; Her spirit seemed as seated on a throne. Apart from the surrounding world is not in love with Juan, she is just eager to save Juan from the duchess. However, she who would not spare a glance for an ogling, handsome seducer is soon also in danger of and strong. In its own strength, most strange in one so young. (XV. 45, 47) Although young, she is like the sad but wise observer of the world’s follies, falling in love with Juan: She was, or thought she was, his friend--and this Without the farce of Friendship, or romance self-contained and removed, untainted by the world and yet fully aware of the expulsion from Eden. But, whereas Haidee had been a fragile Of Platonism, which leads so oft amiss Ladies who have studied Friendship but in FranceOr Germany, where people purely kiss. (XIV.92) innocent, Aurora has an inner strength that the poet admires even as he is puzzled by it. Small wonder that even Adeline understands her not at all: “She marvelled what he saw in Byron teases the sport of Platonism, revealing it as a kind of innocent hypocrisy. He warns the reader not to jump to any conclusions. He is content to leave them hovering, as the effect is fine. “It is not clear that Adeline and Juan / Will fall; but if such a baby / As that prime, silent, cold Aurora Raby?” (XV. 49). It is this lack of possible comprehension that fascinates Byron: he has found in Aurora the image the whole poem has been looking for, the emblem of they do, 'twill be their ruin” (XIV. 99). Aurora Raby is compared with Haidee, though her communicative mode of silence something on the verge of understanding. In the brittle social world of London, so dexterously demolished in the later cantos, would suggest that association resemble not his “lost Haidee; / Yet each was radiant in her proper sphere” (XV. 58). Among the three ladies, Juan is impressed most with she does indeed stand out like a “star.” She grows quietly like a flower, her heart serene and detached from the world. It would be futile to speculate on the model for Aurora Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 303 within Byron's experience in English society. At any rate more attention is given to her personality than that of any character other than Adeline, who “happened” to omit her there is some truth in it as far as it goes, for Byron had firsthand knowledge of society. He shows its members engaged in intrigue among themselves, maintaining a polite from the list of eligible women for Juan. But Aurora Raby is seemingly unaware of Don Juan's presence. She is not dazzled by Juan as the other women are because “she front while ceaselessly trying to win selfish advantages for themselves. In this English world, the assumption of Juan's place as a signifier in a complex but did not pin her faith on feature”(XV. 56). Nor is she impressed by his fame, which sometimes “plays the deuce with mankind,” for he has the reputation of “Faults which ascertainable system of social discourse support the narrative. Lady Adeline Amundeville makes him her protégé, and advises him freely on affairs of the heart. attract because they are not tame” (XV. 57). Aurora embraces thoughts that are boundless; goes, in other words, beyond the The Duchess of Fitz-Fulke also demands a secluded spot where there is no danger of intruders. Lady Adeline urges him to select bounds that restrict and clog the rest of us. What allows this liberation is her depth of feeling which matches the depth of her thought. Aurora’s lack of interest only a bride from the chaste and suitable young ladies attentive to him. The prospective brides that Adeline presents to Juan give Byron an opportunity for some riotous serves to spur Juan on to greater efforts. The relationship between Juan and Aurora seems hardly destined to survive the assaults fooling with tag-names –“Miss Reading, Miss Raw, Miss Flaw, Miss Showman, Miss Knowman, and "two fair co-heireses of two other aggressive women. Her purity renews in the increasingly jaded Juan “some feelings he had lately lost, / Or hardened” and rouses him to activity (XVI. 107). Giltbedding” (XV. 40). Don Juan is considering of marriage, but the poet’s own unhappy experience of marriage seems to prejudice him against all matrimony as the The tension resulting from Juan’s relations with different ladies brings some conflicts to the English cantos. But all the characters that Byron creates in London are intended to mirror English aristocratic life in the early nineteenth century. “It is opposite of love. Now tempered by reflection and comparison, Juan has to choose what kind of man he will be, in terms of what kind of woman he will identify himself with. Michael G. Cooke asserts, “The strategic the only section of the poem which actually deals with a social group, and thus is the only episode that would really fit in any placement of the female role trois in Don Juan symbolizes three modes of relationship that the protagonist may experience with proposed plan of treating the characteristic absurdities of the various people of Europe” (Ridenour 111). The reflection is obviously a distorted one, but nevertheless women and through them with the world. Haidee--Aurora represents a timeless world formed of compassion, candor, and love; Julia--Fitz-Fulke represents a sensual world 304 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 marked by brute repetition and monotony; Gulbeyaz--Catherine --Lady Adeline represents an unfeeling but insatiable world characterized by exhausting duty and and pearly teeth: “The phantom of her frolic Grace – Fitz Fulke!” (XVII. 123) Since the poem was left unfinished, the reader cannot know what Byron would have punishment” (77). During the party at the Norman Abbey, an interlude occurs while Juan "mused on mutability, / Or on his mistress–" (XVI. 20). done with these props. But in the context of this apparent absurdity, Juan’s final passing allusion to Aurora is all the more arresting. Unaware of Juan’s confrontation Juan is "petrified" because he has heard a hint of such a spirit, Once, twice, thrice pass'd, repass'd – the thing of air, with the ghost, Aurora looks as though she appreciates to his silence, and raises her esteem: “the love of higher things and better days; / The unbounded hope, and heavenly Or earth beneath, or heaven, or t'other place ; And Juan gazed upon it with a stare, Yet could not speak or move; but, on its base ignorance / Of what is call'd the World, and the World's ways; / The moment when we gather from a glance / More joy than from As stands a statue, stood: he felt his hair Twine like a knot of snakes around his face; He taxed his tongue for words, which were not granted, To ask reverend person all future pride or praise. . . .” (XVI. 108). Aurora is deeply virtuous and quite unworldly, looking with detachment on the follies and the vanities of the beau monde. what he wanted. (XVI) Juan becomes paralyzed because he fears to make visible what he feels but will By her purity and beauty she seems to revive Juan’s nobler emotions, which has been overlaid by his varied sexual adventures. not see. Byron enters in this canto the unexpected realms of Gothic horror. Of the ghost, there is a legend about the Norman Abbey. The Amundevilles have their own These ideal feelings are aroused, however, only for a brief moment. Juan soon passes from sublime musings about Aurora to an involvement with the Duchess of Fitz-Fulk, account of the forefather, who, “came in his might, with King Henry's right / To turn church lands to lay” (XVI. 40). But why does the thing appear only to Juan? Lord Henry provides an explanation in his comments on the “odd story” that “our sire and this is perfectly in keeping with Byron’s view of human nature – Juan’s inconsistency and his inability to resist temptation. Through Don Juan finding himself in the aristocratic world of early nineteenth-century England, Byron exposes had a more gifted eye / For such sight” (XVI. 36). Later while Juan is sitting in his bed, the black Friar on a monk’s cowl reappears. the shallowness, hypocrisy, and self-interest of that world. Its women have no serious aim in life and its men are dull, pretentious, Juan’s curiosity forces him to chase the phantom all the way until he finds the ghost’s blue eyes sparkling in the moonlight, a sweet breath, a straggling curl, a red lip, and unhappily married. They are all bored and spend their time in social activities of various kinds in the town or in the country. They are all other than what they seem to be. Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 305 There is no genuine virtue in this society; there is only the appearance of virtue, according to Byron. The whole epic becomes an indictment of the state of insight into his views, but he is also deeply moving in his awareness of the transience of human life. In his concern to get at the facts of behavior in English society, he becomes society as Byron himself hoped that “by telling the truth he would awake the world of the evils which blighted its happiness, and expose its respected social system as a increasingly interested in exploring and understanding human personalities rather than in attacking them. He was convinced that what he was writing had in it “the principle of corrupt and corrupting sham” (Bowra, 172). In a letter to B. W. Procter, Byron describes Don Juan as “a satire on affection of all kinds, mixed with some relief of serious duration.” The record of Don Juan, then, is a record of release and growth as man and artist; canto by canto, the range of Byron’s awareness expands. Byron in the epic had feeling and description” ( A Byron Chronology 85) Although he has attacked contemporary achieved a point of view and method capable of encompassing the complex world in which he lived. “Byron’s achievement in Don poets in Don Juan, and ridiculed some precious romantic ideas in the process, Byron himself is being more daringly Romantic than any others by choosing to Juan,” remarks Bloom, “is to have suggested the pragmatic social realization of Romantic idealism in a mode of reasonableness that no other Romantic aspired to attain” (The rely so much on his own independent judgment as he says, "I mean to show things really as they are." And it is this Visionary Company 271). He had shown a way by which poetry could survive and grow in the nineteenth century as a meaningful tremendous faith in his own judgment that allows him to see clearly the underlying rottenness of English society--its lack of sympathy, spirit, and poverty of imagination. social art. Byron’s presence and tragic death produced a vital spark of inspiration for the eventual liberation of Greece and proved Byron’s love of truth, virtue, and beauty was as deep and genuine as that of his fellow Romantics. But, where the others were “idealists” who wrote of mankind in the abstract, Byron was neither an idealist nor a cynic but a realist who writes the real men and himself as a poetic metamorphosis becoming “a man of action” (Bowra 151). All the different roles and postures present in Byron’s poems reveal a powerful, self-conscious personality that holds as much fascination for us today as it did for women in the actual world. His sagacity and common sense impelled him strongly toward achievement of some practical good. “Byron Byron’s own era. His works together with his championing of Greek independence, make Byron the most admired of English lived in the world,” Bloom observes, “as no other Romantic attempted to live” (The Visionary Company 272). As a poet, he is eager to favor us with writers abroad. He was an inspiration to authors and patriots throughout the nineteenth century. “The great pleasure of reading Byron,” says Watson, “comes from 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 306 his ability to use the happy accident, to seize upon an invigorating idea, to exploit a situation, to admire, to love, to condemn, to ridicule: in other words, to make the most of New York: Oxford UP, 1964. [11] Byron's Letters and Journals. Ed. Leslie A. Marchand. 12 vols. London, 1973-82. life” (297). His poetry is fundamentally Romantic because in his very difference from the others he is asserting his individuality, he is daring in his use of his [12] The Works of Lord Byron: Letters and Journals. 6 vols. Ed. R. E. Prothero. London: 1989-1901. [13] The Works of Lord Byron: Poetry. Ed. own sensibility and because of his subject-matter. His characters, including himself, are significantly out-of-the-ordinary. E. H. Coleridge. London, 1898-1904. [14] Byron: A Self-Portrait, Letters and Diaries, 1798 to 1824. Ed. Peter Quennell. 2 vols. London, 1950. Reference English Romantic [15] Christensen, Jerome. Lord Byron's Strength: Romantic Writing and Commercial Society. Baltimore: Poets. Oxford: Oxford U P, 1974. [2] The Mirror and the Lamp : Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition.Oxford: Ox ford U P, 1971. John Hopkins U P, 1993. [16] Cooke, Michael G. “Byron’s Don Juan: The Obsession and Self-Discipline of Spontaneity”, in Lord Byron’s Don [3] Berry, Francis. “The Poet of Childe Harold” in Byron’s Poetry. Ed. Frank D. McConnell. New York: W. W. Norton, 1978. Juan. Ed., Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House, 1987. [17] Corbett, Martyn. Byron and Tragedy. [4] Bloom , Harold, ed. Lord Byron's Don Juan. New York: Chelsea House, 1987. [5] ed. Romanticism and Consciousness. London: Macmillan, 1988. [18] Croker, John Wilson. The Correspondence of Diaries of John Wilson Croker. Ed. L. C. Jennings New York: W. W. Norton, 1940. [6] ed. English Romantic Poets. New York: Chelsea House, 1986. [7] The Visionary Company. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1971. [8] Bostetter, Edward. The Romantic 1884, I. Cf.. Byron: The Critical Heritage. [19] Derrida, Jacques. The Post card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. Trans .Alan Bass. Chicago: U of Chicago P,1987. Ventriloquists: Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Shelley, Byron. 1963. Seattle and London: U of Washington P, 1975. [20] Emerson, Sheila. “Byron's 'one Word: the Language of self- Expression in Childe Harold III.” Studies in [9] Bowra, Maurice. The Romantic Imagination. Oxford: Oxford U P, 1980. [10] Byron, George Gordon. The Complete Poetical Works of Lord Byron. Romanticism. 20, # 3, 1981. The Trustees of Boston U, 180. [21] England, A. B. Byron's Don Juan and Eighteenth-Century Literature: A [1] Abrams, M. H. Hwong Chang Liou, Lishu Chang Chien : A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 307 [22] Study of some Rhetorical Continuities and Discontinuities. London: Associated U P, 1975. [23] Fowler, Alastair. A History of English U P, 1968. [37] Ed. Byron’s Letters and Journals. 12vols. London: 1973-82. [38] Meisel, Martin. Realizations; Literature. 1987; Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988. [24] Fraistat, Neil, ed. Poems in Their Lace: The Intertextuality and Order of Narratives, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-century England. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1983. [39] Mccalman, Iain. An Oxford Companion Poetic Collections. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1986. [25] Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1957. to the Rmantic Age: British Culture 1776-1832. Oxford Oxford Up, 2001. [40] McGann, Jerome J. Fiery Dust: Byron's Poetic Development. Chicago: [26] Gardner, Helen. “Don Juan” in English Romantic Poets. Ed., M. H. Abrams.Oxford: Oxford UP, 1975. U of Chicago P, 1968. [41] Don Juan in Context. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1976. [27] Jackson, J. R. de J. Poetry of the Romantic Period. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980. [28] Jump, John, ed. Childe Harold's [42] The Beauty of Inflections: Literary Investigations in Historical Method and Theory. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1985. [43] McKusick, James C. Green writing: Pilgrimage and Don Juan. London: Macmillan, 1973. [29] Byron. London: Routledge & Kegan Romanticism and Ecology. Hampshire: MacMillan P, 2000. [44] Page, Norman. A Byron Chronology. Paul, 1972. [30] Knight, Wilson. Byron: A Collection of Critical Essays. Prentice Hall, 1963. [31] Lupak, Mario John. Byron as a Poet of Houndmills: Macmillan, 1988 [45] Pounter, Daivd. “Don Juan, or, Deferral of Decapitation: Some Psychological Approaches” in Don Juan. Ed. Nigel Wood. Nature: The Search for Paradise.Lewiston: Edwin Mellen P, 1999. [32] Manning, Peter J. Reading Romantics: Texts and Contexts. New York :Oxford UP, 1990. [33] “The Byronic hero as Little Boy” in Buckingham: Opening UP, 1993. [46] Raimond, Jean. and Watson, J. R. eds. A Handbook to English Romanticism.New York: ST. Martin's Press, 1992. [47] Read, Herbert. The True Voice of Feeling Lord Byron’s Don Juan. Ed. Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1987. Studies in English Romantic Poetry. London; Faber and Faber, 1953. [48] Richards, I. A. Practical Criticism. [34] Marchand, Leslie A. Byron: A Portrait. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1970; [35] London: Random House, 1993. [36] Byron's Poetry. Cambridge: Harvard London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1929. [49] Ridenour, George M. The Style of Don Juan. Yale UP, 1960. [50] Roboson, W. W. “Byron and Sincerity” 308 黃埔學報 第四十九 第四十九期 民國九十四年 English Romantic Poets. Ed M. H. Abrams. Oxford: Oxford U P, 1975. [51] Rogers, Pat. The Oxford Illustrated History of English Literature. Oxford: [58] Trilling, Lionel. The Liberal Imagination. New York: Harcourt, 1978. [59] Trueblood, Paul G. Lord Byron. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1977. Oxford U P, 1987. [52] Rutherford, Andrew, ed. Byron: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. New York: Barnes, 1970. [60] Waston, J. R. English Poetry of the Romantic Period 1789-1830. New York: Longman, 1992. [61] West, Paul, ed. Byron: A Collection of [53] Byron: A Critical Study. 1961. Stanford: Stanford U P, 1967. [54] Scott, Walter. Quarterly Review. , XVI, 1818, 172-208. Cf. also, Byron: A Critical Essays. N. J. : Englewood Cliffs, 1963. [62] Wilson, John. Edinburgh Review. September 1818, XXX, 87-120. Byron: Critical Study. Shilstone, Frederick W, ed. Approach to Teaching Byron's Poetry. New York: MLA, 1991. [55] Smeed, J. W. Don Juan; Variations on a Theme. London and New York; Routledge, 1990. [56] Storey, Mark. Byron and the Eye of The Critical Heritage, 1970. [63] Wood, Nige, ed. Don Buckingham: Open U P, 1993. Juan. [64] Wordsworth, Jonathan. Visionary Gleam: Forty Books from the Romantic Period. London: Woodstock Books; New York: Woodstock Books, 1994. Appetite. Hampshrine: Macmillan, 1986. [57] Swinburne, Charles. The Critical Heritage. Ed. Rutherford Andrew. New York: Barnes, 1970. A Discourse on Byron’s Don Juan 劉煌城 張簡麗淑 摘要 本論文針對拜倫之長詩『唐璜』探討其詩藝及拜倫式英雄的真正蘊涵,透過浪漫之 追尋,拜倫式英雄展現某種風流與漂蕩之特質,致使某些評論或言說嘲諷拜倫的詩傷風 敗俗。本文以浪漫詩理論為本,社會文脈為輔檢視、分析『唐璜』詩中教育,性/性別, 愛情,婚姻,倫理與道德之相關意涵。拜倫的詩筆鋒看似嬉笑,實則暗諷。長詩『唐璜』 裡的英雄人物批判當時重工業及英軍遠征造成的環境危機。唐璜的憤世嫉俗中隱含著無 邊的愛,並關懷人與自然相互依存的共生關係,以及他無怨無悔追尋伊甸園的決心,就 此我申辯拜倫實為一具高度道德感的詩人。 關鍵詞: 關鍵詞 :拜倫式英雄、 社會文脈、道德、伊甸園、共生