silence is not always consent: employee silence as a

Running head: SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT: EMPLOYEE SILENCE AS A

BARRIER TO KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

Dr. Robert Bogosian

By

1 , RVB Associates: rob@rvbassociates.com

&

James E. Stefanchin, The George Washington University: jstef@gwu.edu

Keywords: Employee Silence, Knowledge Transfer, Innovation

1

1 For correspondence, contact Dr. Rob Bogosian at 11766 Quail Village Way, Naples, FL

34119 | (617) 869-0687 | Fax: (800) 722-4373 | rob@rvbassociates.com

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT

Silence is not always Consent: Employee Silence as a Barrier to Knowledge Transfer

2

Silence may be deemed as consent or affirmation, compliance or acquiescence, or it may indicate dissent or dissatisfaction in a climate in which speaking up may be seen as useless or dangerous.

- Blackman & Sadler-Smith

Introduction

The concepts of employee silence and knowledge transfer have been studied separately and received a modest amount of attention by scholars and practitioners.

However, the relationship between silence and knowledge transfer has not been adequately explored. Employee silence is characterized as the willful withholding of relevant and important work related information (Bogosian, 2011). The assumption that silence implies agreement is a longstanding (albeit misunderstood) guideline of social interaction.

Communicating one’s assumptions, beliefs, and knowledge is a requisite for effective operations within rational systems. The social contributions of voice can be seen in organizational processes of managing agreement (Harvey, 1974), managing conflict

(Pondy, 1967), managing sensemaking (Lüscher & Lewis, 2008; Weick, 1995), managing knowledge (Davenport & Prusak, 2000; Nonaka, 1994), and innovation (Baer & Frese,

2003; Sanz-Valle et al., 2011; Brown & Eisenhardt, 1995; Jimenez & Valle, 2011;

Cavagnoli, 2011) amongst others. However, very little is known about the potentially negative influence that silence has on an organization’s ability to transfer knowledge.

The phenomenon of silence, in the context of managing knowledge, can be seen as the product of agents being silent; or being silenced (Blackman & Sadler-Smith, 2009).

According to Blackman and Sadler-Smith (2009), in their work on knowing and learning, the former is a subjective view of knowledge that cannot be spoken or that might be spoken. The latter, those that are silenced, either unconsciously repress or consciously withhold their voice; or, their voice is consciously suppressed due to external influences.

Employee silence can be an offensive or defensive response mechanism (Bogosian, 2011) to manager practices perceived by the employee as egregious.

Milliken, Morrison and Hewlin (2003) posit that there are several antecedents and consequences of organizational silence. The antecedents, they claim, exist at the individual manager, management team, and organizational levels. Management practices are one such example contributing to employee silence (Morrison & Milliken, 2000).

Employees who remain silent about relevant work issues that could inform their managers and organizations are in effect preventing the transfer of potentially valuable information.

Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001) view organizational knowledge as capabilities realized by organizational members. These capabilities are related to an ability to draw work-related distinctions, which are contextually bound. Effectively managing organizational knowledge requires managers and leaders to focus more on the socialization aspects of organizing versus the attention given to digitally stored and utilized knowledge.

This type of attention will allow the experience and knowledge of one unit to affect

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 3 another; thereby enhancing the orientations of an innovation oriented organization. It is our position that an innovation-oriented organization is one that embraces change (Vesey,

1991) and successfully implements ideas, products, and services in the market for which it serves (Jimenez & Sanz-Valle, 2011).

Knowledge is both a source of , and a barrier to innovation (Carlile, 2002). This paper examines the phenomenon of silence and its potential impacts on the collective construct of organizational knowledge transfer. We argue that leaders must be mindful of the practices that contribute to a climate of silence. Additionally, we put forth a proposal for future research that examines the effects of silence on the knowledge transfer process.

This proposal is in response to Argote, McEvily, and Reagans’ (2003) call for work to address some of the “dysfunctional” aspects of relationships.

Theoretically, this paper will attempt to further our understanding of knowledge transfer. Specifically, we will attempt to inform current thinking about how the influential construct of employee silence affects knowledge transfer within the workplace. Through a detailed literature review and synthesis, propositions will be presented which are intended to frame a future, empirical research agenda. The practical significance of this article will be realized in its ability to inform leaders’ and organization development practitioners’ understanding of the social phenomenon of employee silence and how antecedents such as management practices can positively or negatively impact the transfer of knowledge. This will be of particular interest to those charged with the development, oversight, or modification of systems that contribute to an organization’s strategic renewal.

This intent of this paper is to analyze the relationship between employee silence and knowledge transfer within innovation oriented organizations. We will address the implications associated with those who willfully withhold work related information at the individual level of analysis. First, we examine the current literature on leadership practices, employee silence and knowledge transfer. Then, we will explore the conditions under which knowledge transfer occurs in organizations at the individual level and the consequences of effective knowledge transfer. This is followed by an exploration of the antecedents and consequences of employee silence in organizations, at the individual level.

To conclude, our analysis will consider the ways in which employee silence can affect knowledge transfer within innovation-oriented organizations.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

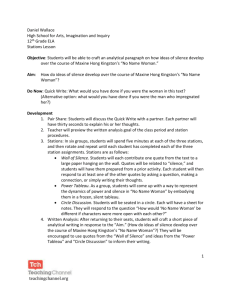

We draw upon several literatures to develop our argument. Figure 1 presents the conceptual frame used to develop our argument. First, we ground our thinking in the silence literature. Silence theory, specifically the work of Morrrison and Milliken (2002) contributes to our understanding of the antecedents and consequences of employee silence.

To understand knowledge transfer in an innovative contex, we leveraged the strategic management literatures. Szulanski’s (1996) work on transfering organizational best practices serves as our anchor for integrating silence. Fostering innovation requires information and knowledge to be deliberately distributed throughout the organization

(Tsai, 2001). Finally, the leadership literature provides our influencing and moderating constructs – those of management practices and transformational leadership.

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 4

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework for Silence and Knowledge Transfer

Leadership Practices

Leadership practices are conceptualized in this article as leadership styles (Bass,

1985). According to Bass, leadership styles are dichotomous and fall into two categories, those that focus on the work and those that focus on the people. Work-focused leadership styles tend to be autocratic, task oriented, and use a centralized decision-making method.

People oriented leadership style is more considerate of the follower (Bass, 1985) and shares decision making and provides support to the follower(s). The dichotomous styles can affect individual follower behaviors in different ways.

Lippitt (1940) posited that democratic (style) leader behavior is encouraging, offering relevant information, empowering, and offers praises to followers. The authoritarian style leader is inclined to determine and announce all policies affecting group members, dictate processes, and give praise in a personal way. Lippitt’s (1940) study split grade school children into two groups, one with an authoritarian style leader and one with a democratic style leader. Children under the direction of a democratic style leader produced more creative and constructive work products than members within the authoritarian style leader group. The children in the group with the authoritarian style leader experienced more interpersonal conflict and resistance toward the leader compared to group members with the democratic style leader. This study showed that a leader’s style can affect individual followers and group member’s behavior.

Leadership theory developed further in the late 20 th century through the research of

Burns (1978) and Bass (1985). James MacGregor Burns (1978) conceptualized leadership as either transactional or transformational. Transactional leaders lead by social exchange.

They exchange things of value with their subordinates to advance their own or their subordinates’ interests. For example, politicians exchange commitments for votes.

According to Northouse (2007), the two significant transactional factors are contingency reward and management-by-exception .

The two transactional leadership factors are: (a) contingency reward where subordinate efforts are exchanged for specific rewards, and (b) management-by-exception which involves negative feedback after action (Northouse, 2007). Transformational

Leadership (Bass, 1985) is a leadership style concerned with improving the follower’s performance to reach their fullest potential. The four transformational leadership factors

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 5 are: (a) idealized influence, (b) inspirational motivation, (c) intellectual stimulation, and (d) individualized consideration (Northouse, 2007).

Contingency reward involves the exchange of subordinate’s efforts for specific rewards. Contingency reward has two aspects (Bass, 1985). Contingent rewarding with intrinsic rewards such as praise is associated with transformational leadership. Contingent rewarding with extrinsic rewards such as a pay raise is associated with transactional leadership. Management-by-exception involves corrective criticism, negative feedback, and negative reinforcement (Northouse, 2007). Two types of management-by-exception include active which involves watching for mistakes committed by the subordinate and then taking corrective action and passive , where management intervention occurs only after standards are not met.

Bernard Bass (1985) expanded upon Burns (1978) and House (1976) conceptualization of transformational leadership. Bass (1985) further emphasized the importance of leader’s emotions and argued that transformational leaders motivate followers to do more than what is expected by elevating their consciousness about the value of goals, encouraging followers to think beyond their own interests to those of the team, and by addressing higher level needs (Northouse, 2007). According to Bass and

Riggio (2006), transformational leaders stimulate and inspire followers to achieve higher performance levels and in the process develop their own leadership capacity.

Bass and Riggio’s (2006) meta-analysis shows that transformational leadership correlates to higher levels of organizational commitment and individual performance.

Individual performance is defined in their study as accomplishment of stated work goals.

Transformational leaders share their power with subordinates and value associates contributions, ideas and input more than transactional (directive) leaders (Larson, et al.,

1998). Transformational leaders who use organization learning straetgies have been shown to influence innovation (Hsiao, H. & Chang, J., 2011). Research shows that transformational leaders (participative style) discussed more shared and unshared information in groups (Larson, et al., 1998) than directive leaders. Maier (1967) argued that it is the leaders responsibility to facilitate discussion among team members and to solicit minority opinions (Maier & Solem, 1952) which results in information flow.

Current research has focused on the positive influence that the transformational leader has on the flow of information (Gumusluoglu and Ilsev, 2009) that contributes to innovation. According to Gumusluoglu and Ilsev (2009) transformational leaders promote idea generation and stimulate creativity and exploratory thinking that are antecedents to innovation. Creativity and thought expression create a healthy organizational climate and psychological safety (Kahn, 1990) for innovation, which is linked to organizational performance (Baer and Frese, 2003). Leadership practices associated with eliciting silence, specifically those characterized as abusive, are explored next.

Most recently, research has focused on abusive leadership. According to Tepper

(2007) abusive leadership can take many forms such as sexual harassment, physical harm, and non-physical hostility. Abusive leadership affects approximately 13.6% of US workers and inflicts high emotional and medical costs. Abusive behavior “most commonly occurs in the form of public ridicule, angry outbursts, taking credit for subordinates successes, and scapegoating subordinates” (p. 262). The effects of abusive leadership

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 6 often transcend to the personal lives of victims. According to Tepper et al. (2006), employees who perceive their supervisors as abusive are less satisfied at work, less committed to their organizations, less trusting of their coworkers, more psychologically distressed, are willing to resist their supervisor’s influence attempts and, less willing to perform pro-social organizational behavior. Procedural injustice may precede abusive leadership (Tyler, 1989). According to Tyler (1989), procedural injustice is characterized as denied voice and decision control, breeds resentment and a desire to “retaliate against those who are blameworthy” (p. 103).

The leadership practices review underscores the complexity and contributing factors that elicit employee silence and encourage voice. The literature and seminal work on leadership shows that transformational leadership encourages employee voice and the flow of work related information. Transactional and abusive leadership practices are associated with silence. What follows is an examination of employee silence, knowledge strategies and knowledge management strategies.

Employee Silence

This article conceptualizes employee silence as, “the withholding of any form of genuine expression about the individual’s behavioral, cognitive and/or affective evaluations of his or her organizational circumstances to persons who are perceived to be capable of effecting change or redress” (Pinder & Harlos, 2001, p. 334). Morrison &

Milliken (2000) conceptualize silence as an organizational level phenomenon. However, recent research (Bogosian, 2011) shows that silence is constructed at the individual level and through a socialization process, becomes an organizational level phenomenon. This article uses the constructs, employee silence and organizational silence interchangeably.

Employee voice is conceptualized in this article as, “a broad term that encompasses all forms of employee speaking-up behavior, characterized by the underlying intent” (Greenberg & Edwards, 2009, p. 7). In the late twentieth century, Toyota assigned

Takeshi Uchiyamada, Chief Engineer, to lead the development of the Prius automobile.

Uchiyamada assembled a cross-organizational team of experts to collaborate on the development of Prius (Liker, 2004). The development process was collaborative and experts were able to share their knowledge openly.

At Disney Corporation, everyone is expected to have a voice in suggestions

(Capodagli & Jackson, 2007) for innovations. Walt Disney insisted that hierarchy be secondary to the transfer and sharing of ideas and he insisted that no idea was “crazy”. In

1937, Disney sent associate Jake Day to the woods of Maine to photograph the outdoors.

In 1942, the motion picture Bambi was released. These two organizations illustrate examples of knowledge transfer and innovation and functioning within a climate of voice versus a climate of silence (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). However, the leadership beliefs that encourage voice, the ensuing knowledge transfer and innovation are not always prevalent. Leader beliefs about position, power and authority can result in a sense of futility (Edmondson, 2003; Morrison & Milliken, 2000) which is known to elicit silence.

On April 20, 2010, a British Petroleum oil well in the Gulf of Mexico exploded, killing 11 workers and spilling millions of gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

British Petroleum had permission to drill for oil without securing the proper permits from

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 7 the federal Minerals Management Service. Scientists at the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration frequently warned of the dangers of drilling in the region.

Senior-level managers silenced them and building permits were granted to the oil company over objections voiced by scientists and environmentalists. The silencing and disregard of scientists and environmentalists alike has resulted in a disaster that is said to have reached epic proportions. The environmental, political, and social consequences of this case are still not fully known. The BP example illustrates how employee silence can have farreaching effects on individuals, organizations, and societies. Employees who remain silent about information crucial to management decisions and organizational development are in effect preventing the flow of new information, decreasing organizational learning

(Blackman & Sadler-Smith, 2009), and in some cases contributing to organizational fiascoes.

Organizations in the twenty-first century are more complex (Uhl-Bien, Marion &

McKelvey, 2007) than ever and require rapid expansion and distribution of knowledge capital. Complexity highlights the challenges of achieving competitive advantage through knowledge capital and innovation. Research has shown a link between innovation, knowledge transfer and firm performance (Baer & Frese, 2003; Jimenez & Sanz-Valle,

2011). Transformational leadership (Bass, 1985) practices have been shown to have a positive influence on the organizational climate required for effective, innovation dependent knowledge transfer (Baer & Frese, 2003; Cavagnoli, 2011; Larson, Foster-

Fishman & Franz, 98). According to Jimezen and Sanz-Valle, innovative organizations achieve better performance results compared to non-innovative organizations. Baer &

Frese (2003) assert that innovation is more likely to occur in a healthy and supportive organizational climate and when psychological safety is present. In this context, individual agents are more likely to share acquired knowledge within the organization. Silence can interrupt the knowledge transfer required to strengthen knowledge capital and contribute to innovation.

Organizations must expand their theoretical knowledge of the antecedents and consequences of silence and the implications for knowledge transfer in innovation oriented organizations. Organizational context can affect the transfer of knowledge (Szulanksi,

2000) at the group or individual agent level. Szuzlanski (2000) asserts that an organizational context that facilitates the inception and development of knowledge transfer is referred to as fertile . An organizational context that hinders the inception and development of knowledge transfer is said to be barren . This article posits that silence is a hindrance to the inception and development of knowledge transfer, thus it creates a barren context that can have negative consequences for organizational innovation.

Individual silence and voice behavior has been studied minimally in the organizational sciences, communication theory, and leadership theory. Silence and voice emerged in the literature when Hirschman (1970) first used the terms exit , voice, and loyalty to describe individual responses to dissatisfaction in customer-supplier relations.

According to Hirschman, clients and organizational members make choices about the effort they expend to correct problematic work situations. It is possible however, to conceptualize silence and voice on a continuum where employees choose to voice their concerns about work related issues rather than remain silent depending on the specific situation (Milliken, Morrison and & Hewlin, 2003). In the organizational fiascoes

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 8 mentioned above, employees chose silence over voice, thereby preventing the transfer of potentially valuable knowledge, which ultimately led to disastrous results.

Morrison and Millken’s (2000) theory of organizational silence proposes three levels of managerial antecedent variables that contribute to a climate of silence which result in organizational silence. They are, implicit managerial beliefs , managers’ fear of negative feedback, and managerial practices . First, implicit managerial beliefs is defined as the underlying beliefs managers hold about their employees. For example, managers may believe that if left alone, employees cannot be trusted to do the right thing (Redding,

1985). Another underlying beief is that managers know what is best for the organization.

The belief that organizational conformity and cohesion is a sign of strength and that conflict and disagreement should be avoided and “managed,” that is, eliminated, are common beliefs held by managers. Second, managers’ fear of negative feedback is based on the theory that people are often afraid of negative feedback whether the information is about them personally or about an intitiative or idea that they endorse or advocate.

Proposition 1: A leaders belief that non-conforming views expressed by employees constitutes dissent will silence and slow the pace of knowledge transfer via discourse.

Organizational silence is an upward communication flow dynamic (Conlee &

Tesser, 1974; Glauser, 1984; Reed, 1962; Roberts & O’Reilly, 1974; Rosen & Tesser,

1970) that has been described as “voice” and “mute” (Bies & Shapiro, 1988).

Organizational silence, when viewed as an individual choice, involves a decision about whether to have a voice or to remain silent in context of an organizational problem that affects the individual employee (Lewin & Mitchell, 1992; McCabe & Lewin, 1992;

Withey & Cooper, 1989). Remaining silent about organizational problems can result in a decision to leave the job or remain silent if the cost of voice is too high or if there is no upward communication mechanism (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). In addition, organizational silence can stifle organizational learning by restricting the amount and flow of information that could affect decisions and informs problem-solving and innovation processes.

Blackman and Sadler-Smith (2009) assert that knowledge is primarily contained among individuals and is then transmitted via paper, electronic devices, or through discourse. The implication is that there is an abundance of latent knowledge waiting to be voiced. They argue that if individuals remain silent about work issues, (potentially valuable) knowledge transfer does not occur. The challenge for practitioners and leaders is to recognize the symptoms of silence, reduce or eliminate individual leader practices that elicit silence, and develop leader practices that encourage voice.

Van Dyne, Ang, and Botero (2003) conceptualized organizational silence as a multi-dimensional construct and present three types of silence, acquiescent silence, defensive silence, and prosocial silence . Acquiescent silence is described as an intentionally passive silent behavior. Defensive silence is described as deliberate omission of work related information based on fear or reprisal. Prosocial silence is withholding of work related information for the benefit of others including the organization. The authors suggest that employee silence is not the opposite of employee voice and argue that

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 9 motivation is the key link to silence and voice constructs. Their conceptual model suggests that employee silence is motivated by fear, disengagement, or cooperation. Morrison and

Milliken (2000) posit that employees take their cue from management on the issues about which they should remain silent. Employees decide whether speaking up is worth the risk.

The tolerance for pluralistic thoughts, those that are varied, is often not present in organizations and is a consequence of the management belief that conformity is good.

Proposition 2: Employees will not engage in discourse for the purposes of knowledge transfer when the formal leader discourages the expression of minority view and opinions.

Recent research by Detert & Trevino (2010) showed that 93% of study respondents claim that their immediate supervisor strongly influences voice behavior. According to

Detert & Trevino (2010), supervisors contribute both positive and negative voice perceptions. They tell us, “supervisors contribute to positive voice perceptions when they are open, empathic, tolerant and composed; they negatively contribute to voice perceptions when they are perceived as abusive, closed or unwilling to accept mistakes” (p. 254).

Leadership practices are discussed next.

KNOWLEDGE AND ASSOCIATED STRATEGIES

Definitions of knowledge in the 21 st century have migrated towards a complex system view. In light of uncertainty (Tywoniak, 2007), knowledge can be seen as a mix of values, experiences, and information (Davenport & Prusak, 2000) that enables individuals and organizations (Tsoukas & Vladimirou, 2001) to draw distinctions. Through the communicative process, stores of knowledge are developed that may be used in current and future operations, ensuring survival (Inkpen, 2000). In this paper, knowledge is seen as objective (Bell, 1973; Habermas, 1971) and goal oriented (Schwandt, 1997; Schwandt &

Marquardt, 2000; Spender, 1996). We assume the conceptualization of knowledge put forth by Spender (1996), in that knowledge is “conceived as a competent goal-oriented activity rather than as an abstract” (p. 57).

The economic crisis has created a stormy marketplace. Additionally, rapidly evolving technologies, constant market pressures, increasing competition, and growing customer power have all necessitated the need for organizations to focus on their knowledge assets. An organization’s context will drive its strategies. Those that are reliant upon physical products and services will likely align intellectual assets much differently than knowledge-based organizations (Zack, 1999).

Knowledge strategies run along two axes. One is the source of knowledge, being internal, external, or unbounded (Zack, 1999). Those relying primarily on internal sources to transfer knowledge incorporate a leveraging strategy whereas those that orient externally, to tap new knowledge domains, are said to employ an appropriating strategy

(Von Krogh, Nonaka, & Aben, 2001). Organizations that do not restrict the source of knowledge are considered to be unbounded (Zack, 1999). The second axis is how an organization uses knowledge; it is either an exploiter, and explorer, or an innovator. An

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 10 organization is considered to be an innovator when it is able to balance its exploitative and explorative functions, draw both internally and externally upon knowledge resources, and focus on radical as well as incremental learning (Bierly & Chakrabarti, 1996; Zack, 1999).

There are distinct differences between an organization’s knowledge strategy and its knowledge management (KM) strategy (see Denford & Chan, 2011). The former should be viewed in a holistic sense (Casselman & Samson, 2007). It is concerned with the application of knowledge – the alignment of intellectual resources to business strategy in order to achieve competitive advantage in the marketplace. The latter is concerned with structural and technical issues of how an organization manages the knowledge required to meet its stated objectives and goals. To effectively manage knowledge, attention should be directed towards its creation, retention, and transfer (Argote, McEvily, & Reagans, 2003) .

Leadership and culture have received recent, widespread, empirical support for being positively related to the transfer of knowledge within organizations (e.g. Donate &

Canales, 2012; Girdauskien ė & Savanevi č ien ė , 2012; McNichols, 2010; Soosay & Hyland,

2008). Implementing proactive knowledge strategies is highly dependent upon both

(Donate & Guadamillas, 2011). Additionally, internal as well as external structures

(Sveiby, 2001) must be considered. Through the establishment of higher-order organizing principles (Kogut & Zander, 1992), organizations can effectively transfer knowledge rooted in experience.

A knowledge management strategy of personalization assumes knowledge is directly tied to the individual; its transfer occurs through direct social interaction (Hansen,

Nohria, & Tierney, 1999). Individuals collaborate and are motivated to work together in order to provide greater value to the system. Here, interaction gives meaning to action.

Organizations that rely on their social networks to transfer knowledge operate as knowledge communities (Garavelli, Gorgoglione, & Scozzi, 2004). Personalization strategies allow the organization to focus on creative problem solving. This type of knowledge management strategy is best for organizations that pursue innovative strategies

– those that deal in highly customizable products and services. Tasks associated with this type of work are often hard to articulate; therefore, members are rewarded for their proactive engagement with other members.

Knowledge Transfer

Within the literature, terms associated with the movement of knowledge include exchange (Al-Adaileh & Al-Atawi, 2011), flow (Mu, Peng, & Love, 2008), sharing

(Brivot, 2011; Wang & Noe, 2010), and transfer (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Taskin &

Bridoux, 2010). Often, terms are used interchangeably (e.g. Werr, Blomberg, & Löwstedt,

2009). Our paper assumes the perspective of knowledge transfer, as put forth by Argote &

Ingram (2000). Although their work is conceptualized at the macro level, they outline a framework that includes the individual as a basic element of embedded knowledge.

Argote and Ingram define knowledge transfer as “a process whereby one unit is affected by the experience of another” (2000, p. 151). Their definition does not infer boundaries.

Knowledge sources can be either external or internal. Members, or employees, are one of three basic elements containing knowledge within an organization. These members can be moved from one unit to another, thereby effectively transferring resident experience.

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 11

Increasing the compatibility of these internal, and external, social networks results in greater knowledge transfer and increased performance (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Inkpen &

Tsang, 2005). Szulanski (1996), in his work on stickiness, proposed a definition of knowledge transfer that focused on moving best practices within the firm. He views transfer as the “dyadic exchanges of organizational knowledge between a source and a recipient unit in which the identity of the recipient matters” (p. 28). We will argue that individuals, as a basic element of organization, cannot positively affect a group or division if they are silenced. Suppressed, or repressed, voice cannot transfer the experiential knowledge that is required to increase performance. Often, management practices and governing actions are relied upon to facilitate the movement of knowledge. However, research has shown they may not have the intended consequence.

Complexity and formalization have both been shown to have a negative effect on knowledge transfer (Willem & Buelens, 2009). Organizations must learn to not focus solely on the development and maintenance of a knowledge management system, per say.

Instead, incorporating a systems approach to managing knowledge, should proffer greater results. Attention should be focused on the people that bring unique values, experiences, and information to bear on the organization (Bell DeTienne, Dyer, Hoopes, & Harris,

2004) and on creating the best climate in which to share that information. Recognized barriers to knowledge transfer include such things as language (Disterer, 2001; du Plessis,

2008), culture (du Plessis, 2008; Giordano, 2007), and even physical workplace configuration (Lilleoere & Hansen, 2011), among others. We believe the absence of employee silence as a barrier represents a gap in the literature.

There is a vast amount of work, both theoretical and empirical, that focuses on the constructs of knowledge transfer and climates of silence, independently. Support for political interventions that alter the social structures of an organization in order to enhance its learning function can be found in the literature (e.g. Argote & Ingram, 2000; Berends &

Lammers, 2010). However, strategies such as these, we argue, do not account for the

[knowledge transfer] consequences of employee silence. Additionally, we argue, employees are more likely to share work related information (voice) than to remain silent when transformational leadership (Bass, 1985) practices are demonstrated in an organization. Transformational leaders enhance performance quality of their followers by setting high expectations (Bass, Avolio & Berson, 2003). They are concerned with emotions, values, ethics, standards, long-term goals, and treating followers as full human beings (Northouse, 2007).

P3 : Knowledge tranfer occurs via discourse in organizations under the direction of a transformational (Democratic) leadership style more than it will under an autocratic leadership style.

Silence as a Hindrance to the Knowledge Transfer Process

Szulanski (2000) posits that knowledge transfer is not an act but rather a process that depends on the disposition and ability of the knowledge source and recipient. Our remaining propositions focus on the knowledge source and examine silence as a potential

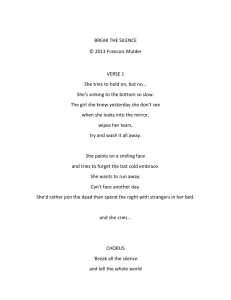

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 12 hindrance to the transfer of knowledge through discourse. Szulanski outlines four, distinct, phases related to knowledge transfer (initiation, implementation, ramp-up, integration) which is depicted in Figure 2, below. We include “Seed” as part of the process that

Szulanski characterizes as the identification of a (knowledge) gap. We incorporate this phased approach to knowledge transfer into our development to better depict the proposed relationship between silence and transfer (See Figure 2). This, we believe, will help structure future research.

Figure 2. Proposal for Study of Silence's Role in the Knowledge Transfer Process

*Note: Adapted from Szulanski (2000)

Initiation

According to Szulanski (Szulanski, 1996, 2000), this stage of the knowledge transfer process entails all actions and events leading up to the transfer. For example, it may include the efforts of an organization to identify the gaps in its current knowledge strategies as well as the coordinating actions to identify the requisite knowledge required to mitigate gap effects. Silence, we propose, increases the difficulty associated with search strategies. Within the literature, it is assumed the source is a willing participant. However, we believe, individuals with either oppressed, or repressed, voice will not adequately articulate knowledge surrounding existing operations. The silent individual, as the source of knowledge will not freely communicate pertinent measures of performance within his or her unit.

P4: Knowledge gaps cannot be accurately calculated in organizations where employee silence exists.

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT

Implementation

13

Once a relevant gap in knowledge has been identified and adequate search strategies are formulated to address the perceived deficiency, the implementation phase of knowledge transfer begins (Szulanski, 1996, 2000). In this phase, resource flow between the source and recipient is critical. Social networks are evaluated for appropriateness.

Activities related to implementation slow after the recipient begins using the knowledge.

According to Szulanski (Szulanski, 1996, 2000), this phase will see increased resource flow and therefore issues associated with transfer and knowledge boundaries may need to be addressed at this stage (Carlile, 2002, 2004). Silence, we believe, will complicate the implementation of knowledge. Individuals may not readily voice issues associated with syntax, interpretations, and goals. Lessons learned during previous transfers must be shared with the recipient. Employee silence may become a barrier to the transfer of issues relating to syntax, interpretations and goals. Individuals, who willfully withhold valuable insights, could cause undue barriers to the implementation phase of knowledge transfer.

P5: Employee silence will compromise the quality and quantity of resource flow between source and recipient.

Ramp-up

Here, the recipient begins using the knowledge. This stage of the transfer process is heavily dependent upon problem identification and problem solving (Szulanski, 1996,

2000). The proposed issues of silence at this stage are with the recipient unit. The absorptive capacity of the recipient depends on the existing knowledge inventory and skills

(source). Therefore, individuals must voice concerns and findings associated with the transferred knowledge. Szulanski (2000) asserts that “the presence of relevant expertise during the ramp-up stage” (p.16) from source to recipient, is critical. Employee silence contributes to the causal ambiguity, excess costs and delays associated with the ramp-up phase (Szulanski, 2000).

P6: Employee silence is associated with excess costs and delays associated with the ramp-up phase.

Integration

Szulanski (Szulanski, 1996, 2000) tells us this stage is marked by the existence of satisfactory results in using the newly acquired knowledge. Use of the knowledge becomes part of the organization’s routines. Routinization of the new practices is facilitated by minimal existence of intra-organizational conflict. While conflict may be beneficial to knowledge creation, silence, we propose, will create unnecessary obstacles to knowledge integration. When obstacles are encountered and unresolved, organizations can respond with threat rigidity (Staw, Sandelands & Dutton, 1981) by reverting back to their

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 14 known and more predictable conditions (status-quo). Szulanski (2000) asserts that successful integration depends on an organizations ability to remove obstacles and commit to an inter-organizational truce. Removing or disciplining individuals who are at the center of disruptive conflict (Szulanski, 2000) may not be a viable solution if the root cause of the disruption is not identified. Employee silence may contribute to the

“difficulties encountered in this process” (p. 16) because information withheld could be crucial to achieving routinization and becoming a knowledge and operational norm.

Unlike more overt obstacles, employee silence by its very nature is difficult to identify and correct without the requisite knowledge to recognize symptoms and antecedent conditions.

P7: Employee silence threatens the routinization of new knowledge by slowing it down or causing a reversion to status-quo.

P8: Without the requisite knowledge of employee silence antecedents, it cannot be detected as a root cause of integration failure.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SILENCE ON KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER IN

INNOVATIVE ORIENTED ORGANIZATIONS

Thus far we have presented a model for how employee silence can effect each phase of the knowledge transfer process within innovation-oriented organizations. Current literature suggests a positive relationship between knowledge transfer, innovation and company performance (Jimenez & Sanz-Vlle, 2011; Baer & Frese, 2003). The silence and knowledge literature have been explored separately. It was not our primary goal to examine the relationship between knowledge transfer and innovation. However, this relationship must be explored further because knowledge transfer encouraged and supported by transformational leadership (Larson, Foster-Fishman & Franz, 1998; Larson,

Abbott & Franz, 1996; Hsiao & Chang, 2011) is a critical component in the innovation process. Our goal was to develop a theoretical argument for further research into the relationship between silence and knowledge transfer in innovation-oriented organizations.

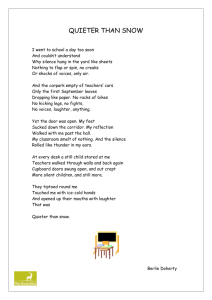

We focused on one of the central causes of employee silence, leadership practices. We expanded upon Suzlanski’s knowledge transfer model by integrating the silence dynamics at the individual level of analysis to develop propositions for further research. Our objective was to establish and bring to light the relationship between employee silence and knowledge transfer. Figure 3 is a graphical depiction of our proposed relationships.

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 15

Figure 3. Effects of Employee Silence on the Phases of Knowledge Transfer

Effects on Organizational Practitioners and Leaders

One significant aspect of knowledge transfer relates to both organizational practitioners and leaders, which is depicted in Figure 3. Employee silence can effect each phase of the knowledge transfer process in several ways that are described next. Employee silence can impede the identification of a knowledge gap, which can prevent an organization from initiating actions to close it. Silence can slow the integration process by preventing critical source knowledge to pass to recipients. The absence of critical knowledge in the integration phase could cause unresolved difficulties that result in delays and cost over runs that result in a reversion to the status quo.

Transformational leadership practices are shown to provide a supportive and tolerant culture where idea and knowledge exchange are encouraged. Autocratic and egocentric leadership practices have been shown to elicit silence. Transformational leadership practices are a strong defense against employee silence and knowledge transfer process breakdowns.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The study of knowledge transfer and silence have been examined separately which has left a void in the organizational literature that explores the relationship between silence and knowledge transfer in innovation oriented organizations. This article explores the relationship by examining the antecedents to effective knowledge transfer and silence separately. We then explored the ways in which the antecedent conditions interacted and the consequences of the interactions for innovation and firm performance.

Organizational complexity requires a level of agility, innovation, idea generation and strengthening that results in sustainable competitive advantage. Scholars have argued

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 16 the benefits of technologically facilitated knowledge transfer however it is the organizational agents (Bierly & Chakrabarti, 1996) who access and use the knowledge to generate new knowledge that can result in competitive advantage. We then explored social network dynamics that enable and restrict knowledge transfer posit that these dynamics must be clearly understood by organizational leaders and practitioners. We argue that silence is a barrier to knowledge transfer. We use Szulanski’s (2000) process framework to present a model depicting where silence is most likely to become a risk to knowledge transfer and the potential consequences to innovation and organizational performance.

Employee silence in organizations is a social phenomenon that is often caused by leader practices perceived to be unjust or egregious by the individual agent. The result is either offensive or defensive silence (Pinder & Harlos, 2001) resulting in a contraction of discretionary effort. The challenge facing organizations experiencing employee silence is that it is difficult to detect. Employees are not likely to self-identify as “silent”.

Practitioners and leaders must have a deep understanding of the silence phenomenon and develop the capability to identify the symptoms of silence and the consequences for knowledge transfer, innovation and firm performance. Next, leaders must develop the ability and possess the willingness to accept feedback, engage in self-reflection and insights to determine how their practices may be contributing to a climate of silence

(Morrison & Milliken, 2000). In addition, leaders must develop the ability encourage voice, and thought diversity in dyadic and group settings.

In conclusion, we posit that the time for further research into the relationship between employee silence, discourse enabled knowledge transfer within innovationoriented organizations, is long overdue. We have shed new theoretical light on this relationship and tried to explain that achieving and sustaining competitive advantage through effective knowledge transfer is more likely to occur when managers demonstrate transformational leadership practices that encourage voice and minimize or eliminate employee silence.

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT

References

17

Al-Adaileh, R. M., & Al-Atawi, M. S. (2011). Organizational culture impact on knowledge exchange: Saudi Telecom context. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15 (2), 212-

230.

Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge Transfer: A Basis for Competitive Advantage in Firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82 (1), 150-

169.

Argote, L., McEvily, B., & Reagans, R. (2003). Managing Knowledge in Organizations:

An Integrative Framework and Review of Emerging Themes. Management

Science, 49 (4), 571-582.

Baer, M. & Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance.

Organizational Behavior , 24, 45-68.

Journal of

Bass, B.M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations . New York: Press

Bass, B. M. & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership . Mahway, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bell, D. (1973). The Coming of Post-Industrial Society—A Venture in Social Forecasting .

New York: Basic Books.

Bell DeTienne, K., Dyer, G., Hoopes, C., & Harris, S. (2004). Toward a model of effective knowledge management and directions for future research: Culture, leadership, and

CKOs. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 10 (4), 26.

Berends, H., & Lammers, I. (2010). Explaining Discontinuity in Organizational Learning:

A Process Analysis. [Article]. Organization Studies, 31 (8), 1045-1068. doi:

10.1177/0170840610376140

Bierly, P. E., & Chakrabarti, A. (1996). Generic Knowledge Strategies in the U.S.

Pharmaceutical Industry. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (ArticleType: researcharticle / Issue Title: Special Issue: Knowledge and the Firm / Full publication date:

Winter, 1996 / Copyright © 1996 John Wiley & Sons), 123-135.

Blackman, D., & Sadler-Smith, E. (2009). The Silent and the Silenced in Organizational

Knowing and Learning. Management Learning, 40 (5), 569-585. doi:

10.1177/1350507609340809

Bogosian, R. (2011). Engaging organizational voice: A phenomenological study of employees’ lived experiences of silence in work group settings (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest database (UMI3489788).

Brivot, M. (2011). Controls of Knowledge Production, Sharing and Use in Bureaucratized

Professional Service Firms. Organization Studies, 32 (4), 489.

Burns, J.M. (1978 ). Leadership . New York: Harper & Row.

Capodagli, B. & Jackson, L. (2007). The Disney way . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Carlile, P. (2002). A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: Boundary objects in new product development. Organization Science, 13 (4), 442-455.

Carlile, P. (2004). Transferring, Translating, and Transforming: An Integrative Framework for managing Knowledge across Boundaries. Organization Science, 15 (5), 555-

568.

Casselman, R. M., & Samson, D. (2007). Aligning Knowledge Strategy and Knowledge

Capabilities. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 19 (1), 69-81. doi:

10.1080/09537320601065324

Conlee, M. C. & Tesser, A. (1974). The effects of recipient desire to hear on news

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 18 transmission. Sociometry , 36 , 588-599.

Davenport, T., & Prusak, L. (2000). Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage

What They Know . Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Denford, J. S., & Chan, Y. E. (2011). Knowledge strategy typologies: defining dimensions and relationships. [Article]. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 9 (2),

102-119. doi: 10.1057/kmrp.2011.7

Detert, J. R. & Trevino, L. K. (2010). Speaking up to higher ups: How supervisors and skip-level leaders influence voice. Organizational Science , 21 (1), 249-270.

Disterer, G. (2001, 3-6 Jan. 2001). Individual and social barriers to knowledge transfer.

Paper presented at the System Sciences, 2001. Proceedings of the 34th Annual

Hawaii International Conference on.

Donate, M. J., & Canales, J. I. (2012). A new approach to the concept of knowledge strategy. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16 (1), 22-44. doi:

10.1108/13673271211198927

Donate, M. J., & Guadamillas, F. (2011). Organizational factors to support knowledge management and innovation. [Article]. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15 (6),

890-914. doi: 10.1108/13673271111179271 du Plessis, M. (2008). What bars organisations from managing knowledge successfully?

International Journal of Information Management, 28 (4), 285-292.

Edmondson A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams . Journal of Management Studies , 40 (6).

Garavelli, C., Gorgoglione, M., & Scozzi, B. (2004). Knowledge management strategy and organization: a perspective of analysis. Knowledge and Process Management,

11 (4), 273-273.

Giordano, R. (2007). An investigation of the use of a wiki to support knowledge exchange in public health.

Paper presented at the 2007 International ACM Conference on

Supporting Group Work, Sanibel Island, Florida.

Girdauskien ė , L., & Savanevi č ien ė , A. (2012). Leadership role implementing knowledge transfer in creative organization: how does it work? Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 41 (0), 15-22.

Glauser, M. J. (1984). Upward information flow in organizations: Review and conceptual analysis. Human Relations, 37, 613-643.

Greenberg, J. & Edwards, M. S. (Eds.) (2009). Voice and silence in organizations .

Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Gumusluoglu, L. & Ilsev, A. (2009). Transformational leadership and organizational innovation: The roles of internal and external support for innovation. Product

Innovation Management , 26, 264-277.

Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and Human Interests . Boston: Beacon Press.

Hansen, M., Nohria, N., & Tierney, T. (1999). What's your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review, 77 (2), 106-116.

Harvey, J. B. (1974). The abilene paradox: The management of agreement. Organizational

Dynamics, 3 (1), 63-80.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

House, R.J. (1976). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt & L. L.

Larson (Eds.), Leadership: The cutting edge (pp. 189-207). Carbondale: Southern

Illinois University Press.

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 19

Inkpen, A. (2000). Learning Through Joint Ventures: A Framework of Knowledge

Acquisition. Journal of Management Studies, 37 (7), 1019-1043.

Inkpen, A., & Tsang, E. (2005). Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer.

Academy of Management Review, 30 (1), 146-165.

Jimenez, D. & Sanz-Valle, R. (2011). Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. Journal of Business Research , 64, 408-417.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33 (4), 692-724.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3 (3), 383-397.

Larson, J. R., Abbott, A.S. & C.C. & Franz, T. M. (1996). Diagnosing groups: Charting the flow of information in medical decision-making teams. J ournal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 71(2), 315-330.

Larson, J. R., Foster-Fishman, P. G. & Franz, T. M. (1998). Leadership style and the discussion of shared and unshared information in decision groups. Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin , 24(5), 482-495.

Lewin, D. & Mitchell, D. J. B. (1992). Systems of employee voice: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. California Management Review , Spring 1992, 95-111.

Liker, J. K. (2004). The Toyota way . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lilleoere, A. M., & Hansen, E. H. (2011). Knowledge-sharing enablers and barriers in pharmaceutical research and development. [Article]. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 15 (1), 53-70. doi: 10.1108/13673271111108693

Lippitt, R. (1940). An experimental study of the effect of democratic and authoritarian group atmospheres. University of Iowa Studies in Child Welfare , 16 , 43-95.

Lüscher, L., & Lewis, M. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking:

Working through paradox. The Academy of Management Journal (AMJ), 51 (2),

221-240.

Maier, N. R. & Solem, A. R. (1952). The contribution of a discussion leader to the quality of group thinking: The effective use of minority opinions. Human Relations , 3(2),

277-288.

McCabe, D. M. & Lewin, D. (1992). Employee voice: A human resources management perspective. California Management Review, 34, 112-123.

McKelvey, B. (2001). Energizing order-creating networks of distributed intelligence:

Improving the corporate brain. International Journal of Innovation Management , 5 ,

181-212.

McNichols, D. (2010). Optimal knowledge transfer methods: a Generation X perspective.

Journal of Knowledge Management, 14 (1), 24-37.

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W. & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees communicate upward and why. Journal of

Management Studies , 40 , 1453-1476.

Morrison, E. W. & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25, 706-725.

Mu, J., Peng, G., & Love, E. (2008). Interfirm networks, social capital, and knowledge flow. Journal of Knowledge Management, 12 (4), 86-100.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation.

Organization Science, 5 (1), 14-37.

Northouse, P. G. (2007). Leadership theory and practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Pinder, C. C. & Harlos, K. P. (2001). Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 20 responses to perceived injustice. Research in Personnel and Human Resources

Management, 20 , 331-369.

Pondy, L. R. (1967). Organizational Conflict: Concepts and Models. [Abstract].

Administrative Science Quarterly, 12 (2), 296-320.

Redding, W. C. (1985). Rocking boats, blowing whistles, and teaching speech communication. Communication Education , 34 , 245-258.

Reed, W. H. (1962). Upward communication in industrial hierarchies. Human Relations ,

15 , 2-16.

Roberts, K. H. & O’Reilly, C. A. III. (1974). Failures in upward communication in organizations: Three possible culprits. Academy of Management Journal , 17 , 205-

215.

Rosen, S. & Tesser, A. (1970). On reluctance to communicate undesirable information:

The MUM effect. Sociometry, 253-263.

Schwandt, D. (1997). Integrating strategy and organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Advances in strategic management, 14 , 337-360.

Schwandt, D., & Marquardt, M. (2000). Organizational Learning: From World-Class

Theories to Global Best Practices . Boca Raton: St. Lucie Press.

Soosay, C., & Hyland, P. (2008). Managing knowledge transfer as a strategic approach to competitive advantage. International Journal of Technology Management, 42 (1),

143-157.

Spender, J. (1996). Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strategic

Management Journal, 17 (2), 45-62.

Staw, B. M., Sandelands, L. E. & Dutton, J. E. (1981), Adminstrative Science Quarterly ,

26, 501-524.

Sveiby, K. E. (2001). A knowledge-based theory of the firm to guide in strategy formulation. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2 (4), 344-358.

Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring Internal Stickiness: Impediments to the Transfer of Best

Practice Within the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (ArticleType: research-article / Issue Title: Special Issue: Knowledge and the Firm / Full publication date: Winter, 1996 / Copyright © 1996 John Wiley & Sons), 27-43.

Szulanski, G. (2000). The Process of Knowledge Transfer: A Diachronic Analysis of

Stickiness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82 (1), 9-27.

Taskin, L., & Bridoux, F. (2010). Telework: a challenge to knowledge transfer in organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21 (13),

2503-2520.

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda.

Journal of Management, 33 (3), 261-289.

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Henle, C. A. & Lambert, L. S. (2006). Procedural injustice, victim precipitation, and abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology , 59 , 101-123.

Tsai, W. (2001). Knowledge transfer in intraorganizational networks: effects of network position and absorptive capacity on business unit innovation and performance.

Academy of Management Journal, 44 (5), 996-1004.

Tsoukas, H., & Vladimirou, E. (2001). What is Organizational Knowledge? Journal of

Management Studies, 38 (7), 973-993.

Tyler, T. R. (1989). The psychology of procedural justice: A test of the group-value model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 57(5), 830-838.

Tywoniak, S. A. (2007). Knowledge in Four Deformation Dimensions. Organization,

14 (1), 53-76. doi: 10.1177/1350508407071860

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S. & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and

SILENCE IS NOT ALWAYS CONSENT 21 employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies ,

40 (6), 1359-1392.

Von Krogh, G., Nonaka, I., & Aben, M. (2001). Making the most of your company's knowledge: a strategic framework. Long Range Planning, 34 (4), 421-439.

Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20 (2), 115-131.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications

Inc.

Werr, A., Blomberg, J., & Löwstedt, J. (2009). Gaining external knowledge - boundaries in managers' knowledge relations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13 (6), 448.

Willem, A., & Buelens, M. (2009). Knowledge sharing in inter-unit cooperative episodes:

The impact of organizational structure dimensions. International Journal of

Information Management, 29 (2), 151-160.

Zack, M. (1999). Developing a Knowledge Strategy. California Management Review,

41 (3), 125-145.