Wing Fluttering by Mud-Gathering Cliff Swallows: Avoidance of

advertisement

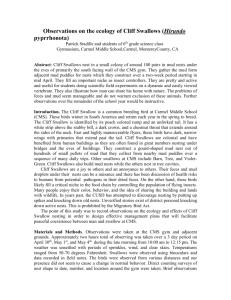

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS Wing Flutteringby Mud-GatheringCliff Swallows:Avoidanceof "Rape" Attempts? ROBERT W. BUTLER CanadianWildlifeService,Box340, Delta, BritishColumbiaV4K 3Y3, Canada Beecherand Beecher(1979) suggestedthat colonially nestingmale Bank Swallows(Ripariariparia) escortedtheir mates7 to 8 days following pair formation to guardagainst"promiscuouscopulations." They observedthat unguardedfemaleswere frequentlychasedby males,and, althoughchasesended in copulationon only threeoccasions, the authors interpretedfemale-escorting behaviorby their mates sized flockson the wing-fluttering behavior of individual swallows, I randomly chosea bird as it arrived at the mud sourceand recordedwhether it fully extended,partiallyextended,or foldedthe wings over the back when it began to gathermud. I then counted or estimated the size of the flock. In addition, I cut a small hole in the side of 27 nests and examined the contents to determine clutch-initiation dates. I found that before egg laying (28 April-4 May) and The Cliff Swallow(Petrochelidon pyrrhonota)alsois during egglaying (5-28 May) swallowsfully extenda colonial nester, but I saw no indication of nor can ed or partially extendedtheir flutteringwings sigI find any referenceto mate guarding. Here, I present nificantly more often in flocksof greater than two data that suggestthat Cliff Swallows flutter their birds than in smallergroups(X2 = 9.2, P • 0.001). wings above their backswhile gatheringmud for During incubationand the nestlingstage(29May-17 their nestsprimarily to reducerapeattemptsand sec- June), however, there was no significantdifference ondarily to reducethe theft of mud pellets used in in wing flutteringbehaviorwith increasingflocksize nest construction. (1-2 birds, 3-5 birds, >5 birds). Furthermore, swalMy studywas conductedApril-July 1980-1981at lows flutteredrather than folded their wings signifthe CrestonValley Wildlife InterpretationCentre, 10 icantlymoreoftenduring egglayingthan eitherbekm west of Creston, British Columbia (49ø10'N, fore or after egglaying (X2 = 15.76,P • 0.001)(Fig. 116ø36'W).The Cliff Swallowcolonyhad been estab- 1). Clearly, wing fluttering increasedin frequency lished in the past 6 yr. A maximumof about 200 with flock size and the onsetof egglaying. completed nests was counted in 1980 and 1981. Cliff Swallowsthat folded their wings appearedto Another Cliff Swallow colony numbering over 500 be attackedby other Cliff Swallowsmore often than nests was locatedabout 1 km away, although those thosethat flutteredtheir wings, althoughthe attacks birds were not observedgatheringnestmaterialwith happenedtoo quickly to be quantified.To test the the swallowsin my study. The colonyin my study hypothesisthat wing flutteringreducedthe frequenbuilt their nests on floor beams supported about 2 cy of attacks,I recordedthe number of attacksdim abovewater by verticalpilings.During my study rected at a stuffed, female Cliff Swallow when her as "mate guarding." about 40 Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica)also nested wingswerewired motionlessin the foldedand flut- in the Cliff Swallowcolony.The colonyis locatedon teringpositions.On 19 May 1980I placedthe model a 616-ha marshthat is dominatedby Equisetumsp., with its wings in the folded positionat a mud-gathCarexsp., and Myriophyllumsp. The Cliff Swallows ering site where swallowsgatheredin flocksof 10gatheredmud from the exposedbanksof a dykelo- 15 individuals. The model was vigorouslyattacked cated within 18 times in 300 s of observation. 50 m of their nests. Attacks resembled In 1981 Cliff Swallowswere first seen at the study area on 13 April. Nest building began by about 25 the copulation attempts describedfor many other birds, includingswallows,althoughsemenwas nev- April, and clutcheswere initiated 5-28 May. Cliff er depositedon the model.Typicallythe attacking Swallowsgathermud by alighting on the ground in bird alighted on the model's back and graspedthe flocksof up to 20 or more birds, raisingthe tail about nape with its mandibles.The attackerthen moved 15øabovethe horizontaland flutteringthe extended its tail in a lateral motion, as if searchingfor the wingsabovethebackwhilepeckingmudintoa pel- model'scloaca,while it vigorouslyflutteredits wings let. That pellet is then flown back to the nest, and above its back. Those attacks lasted about 5-15 s, thepartnersexchange places(Emlen1954,pers.obs.). althoughin four casesthe attackerremainedmountBrown (1910)said that wing fluttering prevented ed for 45 s until it drooped its wings on either side Cliff Swallowsfrom stickingin the mud and soiling of the model and the tips touchedthe ground. Within a few seconds a second bird attacked the first at- their feathers. I noticed, however, that individual Cliff Swallowsflutteredtheir wings more vigorously tackerand both birds departedaftera brief skirmish. when other Cliff Swallows were present than when Someswallowsignoredthe modelat the mud source they were alone.To quantify the effectof various- and gatheredmud aroundand underit. Othersig758 October1982] ShortCommunications 759 lOO Z LU ½r •- 40 2o 0 Fig. 1. Percentageof Cliff Swallowsin various-sizedflocksthat folded, partially fluttered, and fully flutteredtheir wingsbefore(I, n = 78), during(II, n = 103),and afteregglaying(III, n = 216). nored attackerson the model and continued gathering mud. In attacksinvolving live swallows the victim always struggledvigorouslyand usually escaped within a few seconds. I repeatedthe above experiment on the same day using the model, but this time I extendedthe wired the mud source.Resultsdid not differ significantly between the model tests and actual attacks, indicat- ing that habituation to the model had not occurred (Fig. 2). Thoseresultsalsosuggestthat the behavior of live swallowstowards the model accuratelyrepresents the behavior between live swallows. There alsowere significantlymore attacksduring egg layvation. To test that habituation toward the model ing than preceding or following that stage in both had not occurred,! repeatedthe first experimentfor tests(one-sidedProportionTest;Z pre-egg/egg = 3.16, 210 s, which resultedin sevenattacks.Admittedly, Z egg/post-egg = 4.47, P < 0.001). the length of time that the model was not attacked In a few instances,an attackingswallow stolemud would havebeena bettermeasureof attackfrequen- from the attacked bird, while in others the attacks cy than the number of attacks, but the results still appeared to be of a sexualnature. To test whether indicatethat wing flutteringreducesattacksby other Cliff Swallowswere stealingmud from one another, Cliff Swallows. I placed a pellet between the folded-wing model's In one instancewhen no modelwaspresent,I wit- mandibles and placed the model on the mud source nesseda Cliff Swallow attackthree mud-gathering for about300 s during the late egg-layingstage.The Cliff Swallowsin about15 s. It appearedthat the sole model was mounted several times, but no attempt intention of the attackerwas to pounceon the three was made to stealthe mud. That suggeststhat the swallows,becauseit never gatheredmud, although motive for the attackswas not to steal mud pellets, there was plenty of room to do so. Eachtime, the althoughmud stealingmight be moreprevalentdurvictim departedfollowing a brief skirmish.I alsosaw ing the early nest-buildingstage. a Cliff Swallow attack a live Tree Swallow and a dead The reasonfor wing fluttering by mud-gathering Cliff Swallows remains uncertain. ! have shown that Barn Swallow at the mud sourcein May 1980. In 1981,I usedthe folded-wing modelto examine wing flutteringis mostfrequentduringthe egg-laythe seasonalfrequencyof attacksfrom 28 April-16 ing stage.In addition, the attackson the model reJune and comparedthose resultswith the number of sembledcopulationsand were mostfrequentduring attackson live swallowsfrom 2 May-15 June, all at the egg-layingstage.I alsowitnessedCliff Swallows wings. There were no attacksduring 355 s of obser- 760 ShortCommunications [Auk,Vol.99 MODEL 1NATUR o I ]I •I I ]I Fig.2. Thenumberof attacks perminutedirected by CliffSwallows towarda stuffed,folded-wing model andtowardlive Cliff Swallowsbefore(I), during(II), and afteregglaying(III). stealing mud from one another at the mud source, nerableto extra-paircopulations whileguardingthe however. To confuse the issue further, Cliff Swal- nest. I made few observationsof pairs at the nest. Emlen (1954), however, mentionedforced-copula- lows begin egg laying before the nest is complete, so that a mud-gatheringswallowcouldbe building a nest, laying eggs, or both. One possibleexplanationfor the evolutionof wingfluttering behavior of mud-gatheringCliff Swallows is as follows.Cliff Swallowsinvestlargeamountsof time and energyin building the nest. Withers (1977) showed that the daily energy expenditureof Cliff Swallows was greater during nest constructionthan during incubation or nestling periods. At the end of the 1981 nestingseason,only 36% (n = 139) of the Cliff Swallownestsin this study couldsupporteggs, interpretationis that the energeticcostsof building the nest require sharing the duties between both membersof the pair. Cliff Swallowspresumablyare very susceptibleto rape attemptswhile gatheringmud in a tight flock. Hooglandand Sherman(1976)foundthat extra-pair copulations in BankSwallowswereattemptedon the ground.Furthermore,the Cliff Swallowtail-up posture may solicitrape attempts,becauseit resembles the female'scopulatorypostureat the nest. There is so most swallows strong competition within the flock for sites at which must build nests at the start of a tion attempts toward females in their nests. Another new season.That implies that theremight be strong competition for old nests and nest material. I found that nestsfrom previousyearswere occupiedabout 10 days before the swallowsbegan constructionof to gather mud, and alighting Cliff Swallowscould presumablysettlemore easilyon the backof a swallow with foldedwings than on one with fluttering wings. Barlowet al. (1963)found that sunningCliff new nests. In addition, Cliff Swallows steal mud from Swallowsraised their wings to prevent othersfrom one another'snests(Emlen 1954)and from one another settlingon their backs.Any swallow that settledon (this study). The lossof a nestby a pair of Cliff Swal- the back of anothercouldstealits mud or usurpits lows would mean a lossof a largeinvestmentof time spot at the mud sourceregardlessof sex. The same and energy and would favor the evolution of nest would hold true whethera femalealightedon a male guarding. Cliff Swallowsappearto guardtheir nests or a female.If a maleswallowalightedon a female, (Emlen 1954,Mayhew 1958).Emlen (1954)has shown he couldcopulatewith her, stealher mud pellet, or that one member of a mated pair remains in the nest usurpher spotat the mud source.Any swallowthat while the other is at the mud source.After collecting flutteredits wings, however,would reducethe chance a pellet of mud, the swallow returns to the nest and of being settledupon. All of this suggests that natexchangesplaceswith its mate. Nest guarding pre- ural selectionhas favored nest guarding over mate cludesmate guarding and thus freesthe male to seek opportunities for extra-pair copulations with unguarded females.That implies that femalesare vul- guarding in Cliff Swallows. Males could be cuckolded, but they alsohave opportunitiesto cuckoldother males.I never witnesseda rape that appearedto be October 1982] ShortCommunications 761 LITERATURE CITED successful, however, and I believe that successful rapesendingin spermtransferarerare. I neverfound semen deposition on the Cliff Swallow model, although similar studiesby other investigatorshave found semennear the cloacalregionof modelBank Swallows (Hoogland and Sherman 1976) and Savannah Sparrows (Passerculus sandwichensis) (Weather- BARLOW,J. C., E. E. KLAAS, & J. L. LENZ. 1963. head and Robertson 1980). BROWN, F. A. Femalesmight increaseor decrease their fitnessby participatingin extra-paircopulationswith malesof unknown fitness. Presumably,it is to the female's advantageto copulateconservativelywith males of known fitness (i.e. their mates) and not to risk de- creasedfitnessby matingwith othermales. J.P. Goossenassistedin the field, J.P. Savard and G. E. J. Smith provided statisticaladvice, R. J. Can- nings from the VertebrateMuseumat the University of British Columbia supplied some Cliff Swallow models, and M.D. Beecher, D. R. Flook, K. Vermeer, and P. Weatherheadcommentedon the manuscript. I thank all of you. Sunning of Bank Swallowsand Cliff Swallows. Condor 65: 438-448. BEECHER, M.D., & I. M. BEECHER. 1979. Socio- biologyof BankSwallows:reproductivestrategy of the male. Science 205: 1282-1284. 1910. Cliff Swallows. Bird-Lore 12: 137-138. EMLEN,J.T., JR. 1954. Territory,nestbuilding, and pair formationin the Cliff Swallow.Auk 71: 1635. MOOGLAND,J. L., & P. W. SHERMAN. 1976. Advan- tagesand disadvantages of Bank Swallow (Ripariariparia)coloniality.Ecol.Monogr.46: 33-58. MAYHEW,W. W. 1958. The biology of the Cliff Swallow in California. Condor 60: 7-37. WEATHERHEAD,P. J., & R. J. ROBERTSON. 1980. Sexualrecognitionand anticuckoldrybehavior in savannasparrows.Can. J. Zool. 58: 991-996. WITHERS,P. 1977. Energeticaspectsof reproduction by Cliff Swallows.Auk 94: 718-725. Received 19November1981,accepted 11February1982. Effect of Intrusion Pressureon Territory Size in Black-chinnedHummingbirds (Archilochus alexandri) MARY E. NORTON,1'2PETERARCESE, 1 AND PAUL W. EWALDa lWashington StateMuseum,Universityof Washington, Seattle,Washington 98195USA, and 2'aMuseum of ZoologyandMichiganSocietyof Fellows,Universityof Michigan, Ann Arbor,Michigan48109USA Within many avian species,territory size is inverselycorrelatedwith foodabundance(Pitelkaet al. 1955,Gasset al., 1976,Myers et al. 1979).Two hypotheseshave been proposedto explain these correlations:(1) animalsmayassess resourceavailability directly and defend areas that contain sufficient amountsof food, or (2) animals may adjust territory size in responseto an intermediatevariable, intru- mainedconstantor increased,territorysizedoubled. This increasein territory size was attributed to the decreasedintrusion pressure.Similarly, Ewald et al. (1980) documented an inverse correlation between intrusion pressureand territory size in a colony of Western Gulls (Larusoccidentalis).Becausegulls do not forage on their territories,variationsin food abundance could not have caused the variation in sion pressure.By the secondhypothesis,areasof territory size in this colony. Thesetwo hypotheses,however,need not be mugreaterfood abundanceare morecostlyto defend because theyattractmorecompetitors, theresultbeing tuallyexclusive.Hixon (1980)developeda modelof smaller territories. optimal territory size in which he dealt with both food availabilityand intruder density.Integralto his model is the assumptionthat thesetwo factorscan vary independentlyof eachother,but he pointsout teractionof prey density and intrusion pressurewas that disproportionatelyhigh food production in a controlledstatistically,the effectof food densityon given territoryin comparisonwith surroundingterterritorysizewasno longersignificant,yet the cor- ritories might causea concurrentincreasein intrurelationbetween intrusionpressureand territory size sion pressure.Thus, theoretically,thesetwo factors washighlysignificant.Furthermore, whenintrusion canacttogetherand havethe sameeffecton territory pressuredeclinedseasonallywhile prey densitiesre- size. Ewald et al. (1980), Myers et al. (1979) and Hixon (1980)all suggestthat further studiesare needed on 2 Presentaddress:2022 Franklin Avenue East, Seattle,Washington 98102 USA. speciesin which intrusionpressureand food abun- Myerset al. (1979)testedthesehypotheses in studies of winteringSanderlings(Calidrisalba).Their resuitssupportedthe secondhypothesis:when the in-