brooms, beasts, and the phallus: identifying the wicked witch

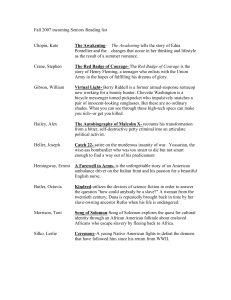

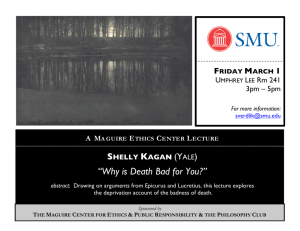

advertisement