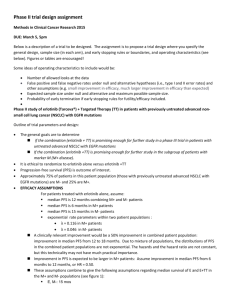

Inhibition of mutant EGFR in lung cancer cells triggers SOX2

advertisement