THE STRATEGIC ROLE OF UNUSED SERVICE CAPACITY Ng

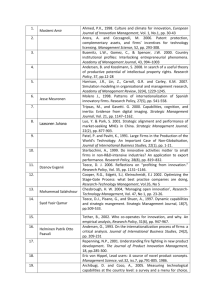

advertisement