ABDOMINAL PAIN

advertisement

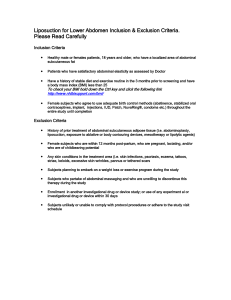

Ron Diekmann, MD ABDOMINAL PAIN Objectives: 1. Distinguish between somatic and referred pain 2. Name the most common abdominal emergencies for each of the major anatomic areas of the abdomen 3. Understand age-related differences in causes of abdominal pain 4. Define the symptom review of patients with abdominal pain and know the significance of different historical presentations 5. Describe the physical assessment of the abdomen 6. Know the value of ancillary testing in evaluation of abdominal pain 7. Provide the major steps in ED treatment of the acute abdomen Copyright UC Regents 1 Ron Diekmann, MD ABDOMINAL PAIN Introduction Abdominal pain accounts for 5% of all emergency department (ED) visits and is an important and challenging component of emergency medicine practice in all centers. There are myriad presentations. Patients may have acute exacerbations of chronic problems (e.g., peptic disease, pancreatitis in alcoholics, inflammatory bowel disease), acute surgical abdomens (e.g., appendicitis, ruptured viscus, acute volvulus) or nonsurgical abdominal emergencies (e.g., gastritis, biliary colic, gastroenteritis). Sometimes abdominal pain is related to acute trauma (e.g., splenic rupture, hepatic laceration, small bowel rupture). The clinical evaluation, diagnostic workup and disposition of patients with acute abdominal pain vary significantly, depending upon the initial history and physical assessment. All patients with abdominal pain do not require diagnostic tests. Sometimes, clinical evaluation alone is sufficient to provide treatment and appropriate disposition. Identification of the patient with an “acute abdomen” requiring immediate surgical intervention, is a critical skill for emergency physicians. Assessment Appearance and general impression: As you approach the patient, consider the degree of pain and note the vital signs. If the patient is obviously uncomfortable, select an analgesic drug for parenteral administration. Sometimes, oral medication is acceptable if the pain is not too severe. But one way or another, treat the pain immediately. If the vital signs are abnormal (HR>100, BP<100, RR >20, T>38), approach the patient with a high degree of vigilance, and obtain vascular access early for diagnostic testing and drug and fluid administration. Pain management If the patient is in pain, give analgesia right away. Ordinarily, use morphine sulfate at 0.5-0.1 mg/kg or 2-4 mg IV or IM. Sometimes, especially if the patient has probable renal colic, use ketolorac 30-60 mg IV or IM. In patients with low or borderline BP, choose the short acting narcotic fentanyl, 0.5-1 ug/kg IV, which is associated with less BP effects. These drugs will not interfere with the physical examination, and in fact will usually enhance the sensitivity of the exam. Tip: Give most patients with severe abdominal pain parenteral morphine immediately. Copyright UC Regents 2 Ron Diekmann, MD History History is the most important part of the assessment. Delineate the character of the patient's pain carefully. There are several essential ingredients of pain: 1. Location—ask the patient where the pain is. There are six anatomic locations: RUQ, epigastrium, LUQ, RLQ, suprapubic, and LLQ. Pain originating in any of these locations may suggest the source of the pathology. Tip: The more midline the pain is, the more likely it is bowel based. Pain that localizes is of high concern and usually requires more diagnostic evaluation. 2. Onset—this is a key characteristic. Explore onset carefully and determine trend of pain over time. Tip: Pain that begins abruptly and is undiminished suggests renal colic, perforated viscus, ischemia (myocardial infarction, testicular or ovarian torsion) or hemorrhage. 3. Severity—this is best evaluated with a familiar 1-10 scale. The value of a pain severity scale for abdominal pain is unknown, but in any single patient it allows assessment of trends and response to therapy. 4. Quality—this is occasionally helpful, but some patients are highly suggestible, or unable to describe pain very precisely. Quality of pain needs to be used with other characteristics for interpretation. Tip: Always inquire if the patient has had pain of this quality before. If yes, consider peptic disease, biliary disease, IBD, hepatitis, and pancreatitis. 5. Radiation (if any)—when present, this is quite helpful. Pain radiating into the back or groin suggests renal colic. Pain into the right shoulder suggests biliary disease. 6. Alleviating and aggravating factors—the effect of eating on pain is especially valuable. Pain that starts or gets worse with eating is usually related to the pancreas and gall bladder. Pain relieved by eating is often peptic disease. Review of systems Associated symptoms are important information to distinguish etiologies. Fever and chills point to a possible acute inflammatory condition. Patients with Copyright UC Regents 3 Ron Diekmann, MD respiratory complaints may have pneumonia with upper quadrant radiation. The presence or absence of anorexia, nausea or vomiting helps diagnose or rule out certain conditions. The absence of anorexia strongly rules against an acute inflammatory condition. Diarrhea suggests gastroenteritis but may be present with 20% of acute appendicitis. Ask women about pregnancy, vaginal bleeding, STDs and LMP. Inquire about bowel movements, melena and hematochezia, and symptoms of UTIs—dysuria, frequency, and back pain. Tip: Be careful calling abdominal pain gastroenteritis if diarrhea is not present. Past medical history Ask about prior abdominal surgeries. Tip: Abdominal pain with vomiting, no flatus or BM, and a midline abdominal scar suggests an SBO. Inquire about medical diagnoses such as DM, HTN, A fib and ESRD. In elderly patients, these conditions are associated with ischemic bowel—an elusive but sometimes lethal condition. List medications and consider iatrogenic causes of abdominal pain. Erythromycin at 500 BID causes abdominal pain in 50% of recipients. Habits Bad habits and co-morbidities strongly influence assessment. Ask about alcohol and quantity of consumption, IVDA, cocaine/amphetamine, HIV and prior bowel problems. Tip: Most alcoholics have some combination of pancreatitis, hepatitis and gastritis. Physical Examination As you begin your hands-on examination, check for: General characteristics 1. patient appearance (extremely important) 2. patient level of distress (after analgesia) 3. diaphoresis ("If the patient is sweating, so should the doctor be.") 4. abnormal vital signs Tip: Persistent fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, or hypotension are red flags for serious abdominal pathology Copyright UC Regents 4 Ron Diekmann, MD 5. body posture. Specifically note if the patient: is writhing about (suggestive of renal, biliary or intestinal colic), prefers to sit, leaning forward a little (suggestive of pericarditis or pancreatitis) Tip: If the patient lies very quietly, often with hips and knees flexed, and does not like to move, consider peritonitis. Complete abdominal examination After completing the rest of the exam, focus on these features of the abdomen. But be sure you have listened to the lungs for crackles, palpated the back for CVA tenderness and looked in the pharynx for pharyngitistonsillitis. 1. Check for peritoneal irritation (rock gurney, ask patient to cough) 2. Inspect the abdomen for distention, ascites, contusions 3 Auscultate for the presence or absence of bowel sounds 4. Percuss the abdomen to determine the presence of percussion tenderness (optional) 5. Palpate the abdomen to determine the location of maximal tenderness, the presence or absence of guarding and/or rebound tenderness, and the presence of masses, organomegaly and/or hernias. Start gently, away from the area of pain, distract the patient, and then palpate more deeply. 6.Try to elicit a Murphy’s Sign. A positive Murphy’s Sign (arrest of inspiration with the examiner’s palpating fingers in the RUQ) suggests irritation in the RUQ. It will always be present in cholecystitis, but may also occur with pancreatitis, hepatitis and even peptic disease. 7.Consider eliciting other signs, to evaluate specific anatomic areas for tenderness: a. Psoas Sign (extend patient’s leg at hip with patient in lateral decubitus position (to move psoas muscle). b. Obturator sign (flex and externally and internally rotate hip) c. Rovsings Sign (palpation in LLQ causes pain in RLQ suggestive of appendicitis). 8. Do a rectal examination to rule-out a mass or foreign body and to determine the presence of tenderness or blood. Always document whether there is rectal tenderness, the color of the stool (brown or black) and whether it is heme+ or heme-. Copyright UC Regents 5 Ron Diekmann, MD Tip: Sometimes tenderness on the rectal examination is the only physical finding in retroflexed appendicitis 9. Do at least a bimanual pelvic examination of women, evaluating only for CMT and adnexal masses. 10. Examine the testicles, scrotum, groin, prostate of males Diagnostic testing Obtain laboratory tests if the diagnosis is not clinically apparent, if the patient is sick, or if there is a suspected complication of a known diagnosis (e.g., rectal bleeding in IBD, fever in diverticulitis). Laboratory testing ("belly labs") CBC Electrolytes and anion gap BUN/Creatinine GlucoseLFTs (transaminases, bilirubin, albumin, alk phos)LipaseUA Upreg Tip: A fever >38, or a WBC > 15K in the presence of abdominal pain suggests a serious etiology. If a clear-cut benign diagnosis such as gastroenteritis or renal colic cannot be established, image the patient. Imaging1. Abdominal CT—workhorse-imaging study. Give contrast orally and IV in most patients. Sometimes rectal contrast is also helpful to look for large bowel problems. Tip: Be careful giving IV contrast in patients with renal insufficiency. Consider ultrasound as an alternative if possible. A high creatinine > 1.5 usually requires bicarbonate and fluid hydration to minimize contrast nephropathy. 2. Abdominal ultrasound—especially good for the gall bladder, ovaries and scrotum 3. Abdominal films—rarely indicated except to evaluate an SBO 4. CXR—useful in upper quadrant pain 5. ERCP—essential for common duct obstruction (gallstones, sludge, compression, stricture) Other ancillary tests1. On patients who are over 40, it is wise to add an EKG. This is especially true in patients who are diabetic and/or who have epigastric pain. 2. ABGs are indicated in patients who are elderly and in severe pain. Acidosis is highly suggestive of intestinal infarction (usually SMA ischemia). Copyright UC Regents 6 Ron Diekmann, MD Differential diagnosis based upon pain type Sudden onset of severe pain which does not diminish renal colic perforated viscous myocardial infarction torsion hemorrhage (e.g., AAA) Crampy pain biliary colic renal colic intestinal obstruction gastroenteritis ectopic pregnancy Severe pain renal colic intestinal infarction dissecting aortic aneurysm perforated ulcer Referred painSome diseases outside of the abdominal cavity manifest as abdominal pain because of shared sensory afferent fibers. For example: 1. myocardial infarction may present as epigastric pain pneumonia in children often appears to be abdominal pain 2. strep tonsillitis may present as abdominal pain. Treatment of Abdominal Pain 1. Fluids—most patients with serious abdominal pain are dehydrated. Unless there is concern for fluid overload in patients with CHF or ESRD, give a bolus of 1-2 liters in adults then a rapid infusion rate. 2. Analgesia—give ongoing pain relief with morphine in most cases. 3. Antibiotics for acute inflammatory processes (cholecystitis, diverticulitis). Many surgeons also request broad-spectrum antibiotics for appendicitis. 4. NG tube—decompress the stomach for SBOs, ischemic bowel or any serious condition where the bowel has stopped working (ileus). 5. Blood transfusion—Use in any symptomatic hemorrhagic event, such as a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm or GI bleed from an active ulcer or IBD 6. Surgical consultation—obtain early in all patients with peritonitis, hemorrhage, ischemia or abdominal pain of uncertain etiology Copyright UC Regents 7 Ron Diekmann, MD Disposition Admit Surgery The surgical service is the best service for patients with acute inflammatory conditions (appendicitis, cholecystitis, cholangitis), ruptured viscus, severe third spacing (hemorrhagic pancreatitis), ischemic bowel, incarcerated hernia, or SBO. Medicine The medical service is usually the preferred service for hepatitis, most pancreatitis, peptic disease, IBD, gastroenteritis, pyelonephritis, and GI bleeds. Ob/Gyn The Ob/Gyn service admits ovarian torsion, ectopic pregnancies, PID and TOAs. Urology The urology service admits scrotal and testicular problems and complicated renal colic. Discharge Most patients can be discharged who have normal vital signs, pain controllable with oral analgesia, and minimal exam findings. Sometimes, acidlowering agents or antibiotics are indicated for conditions such as peptic disease or mild diverticulitis. Pepto-Bismol and anti-diarrheal agents, sometimes with antiemetics, are useful for gastroenteritis. Remember to caution patients to return immediately if their pain becomes worse or their condition worsens. Tip: Discharged patients must be able to tolerate fluids without emesis. Copyright UC Regents 8