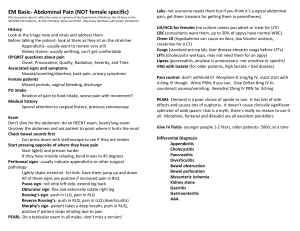

Abdominal Pain

Abdominal Pain

With Dr Sanjay Warrier, Consultant Breast Surgeon at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital

Case 1 – You are in the emergency department where a 50 year old man has just presented with abdominal pain

1.

Initial approach:

Analgesia aids assessment o Ensure there are appropriate lines inserted and analgesia is charted to manage pain

Subjective assessment o General examination of the patient – how well/unwell are they?

Objective assessment o Review the patient’s vital signs (if abnormal, go through ABC assessment and escalate as appropriate)

2.

History:

Assess the pain (Site, Onset, Character, Radiation, Associated symptoms, Timing, Exacerbating and

Relieving factors, Severity)

Associated symptoms should include dysuria, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting

Past medical history

Past surgical history

Embryology o Foregut

Gives rise to oesophagus, stomach, proximal duodenum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen

Supplied by coeliac trunk

Pain typically referred to epigastrium o Midgut

Gives rise to distal duodenum, jejunum, ileum, caecum, appendix, ascending colon, proximal 2/3 of transverse colon

Supplied by branches of superior mesenteric artery

Pain typically referred to the umbilical region o Hindgut

Gives rise to distal 1/3 of transverse colon, descending colon, rectum and upper anal canal

Supplied by branches of inferior mesenteric artery

Pain typically referred to suprapubic region o Visceral midgut pain typically commences as vague pain felt in the umbilical region. As it involves the parietal peritoneal it will become sharper in nature and be localised over the affected organ

Summarised by Dr Abhijit Pal, Resident, RPAH. December 2014

3.

Examination:

Appropriate exposure and position (exposed abdomen, patient supine, arms by side)

Inspection (previous surgical scars, abdominal breathing, guarding)

Palpation (move systematically through all 9 quadrants superficially and then deeply)

4.

Specific diagnoses and signs on clinical examination:

Cholecystitis – Murphy’s sign o Use the edge of your index finger to palpate the abdomen from RLQ to RUQ whist the patient takes deep inspiratory breaths. With each expiration, move your hand closer to the liver’s edge. o During inspiration, abdominal contents are pushed downward as the lungs expand. In cholecystitis, the inflamed gallbladder comes into contact with the examiners hand and results in pain. o Murphy’s sign is considered positive if pain is elicited on palpation of the RUQ during deep inspiration

Appendicitis o Guarding at McBurney’s point.

This is the name given to the point found 1/3 of the distance between the right anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus. o Rovsing’s sign. If palpation of the LLQ increases the pain felt in the RLQ the patient is said to be Rovsing’s positive. o Psoas sign. Flex the right hip joint and rotate it internally and externally. If this results in pain at the RLQ, the patient is said to be Psoas positive.

5.

Quadrants and common differential diagnoses:

RLQ – appendicitis, colitis (older age group), renal colic

RUQ – cholecystitis, cholangitis (particularly if associated with jaundice), hepatitis (especially on background of alcoholism)

Epigastric/central – pancreatitis

LUQ – no specific pathology, usually requires CT to differentiate

LLQ – diverticulitis, renal colic, ectopic pregnancy

6.

Investigations

Bloods o FBC, EUC, LFTs, lipase, coags, group and hold, beta HCG

Bedside o UA o ECG

Imaging o CXR may be considered in a patient with sudden onset abdominal pain and guarding to investigate perforated viscus, which is demonstrated as air under the diaphragm. Also consider a CXR to rule out pneumonia causing upper abdominal pain o AXR is useful to investigate bowel obstruction (i.e. distended abdomen with history of multiple surgeries and associated nausea and vomiting) o CT abdomen

If clinical diagnosis has been made on history and examination and basic imaging, then there is no need for a CT.

Usually indicated for undifferentiated abdominal pain (particularly in elderly patients as their symptoms are often masked)

In vasculopaths who present with non-specific abdominal pain, consider mesenteric ischaemia and ruptured AAA

Unresolving LLQ pain will most likely require CT

Summarised by Dr Abhijit Pal, Resident, RPAH. December 2014

Usually ordered in consultation with surgical registrar

7.

Management:

Liaise with senior ED staff and surgical registrar

If going to theatre, will require IDC, IVF, urine output > 30 mL/hr

Analgesia

Communication with family

Case 2 – You are on the ward and are called by the nurses to review a post-operative patient with worsening abdominal pain

8.

Questions over the phone:

How does the patient look?

Vital signs

Determine urgency and prioritise

9.

Review the notes:

Operation report (operation performed, how long ago, complications/difficulties, intraoperative analgesia and fluids)

Comorbidities

10.

Assess the patient:

Subjective assessment o General examination of the patient – how well/unwell are they?

Objective assessment o Review the patient’s vital signs (if abnormal, go through ABC assessment and escalate as appropriate)

Complete history and examination as mentioned previously

11.

Synthesise information

Differential diagnoses in context of how well the patient is and vital signs and associated symptoms

Consider what day post-op (e.g. D1 post-op may be due to inadequate analgesia vs. D5 and fever may be due to anastomotic leak/abdominal wall infection)

12.

Escalate as appropriate

Surgical review or advice may be appropriate if patient deteriorating or looks unwell

Seek surgical review early in complex patients with generalised abdominal pain

Summarised by Dr Abhijit Pal, Resident, RPAH. December 2014