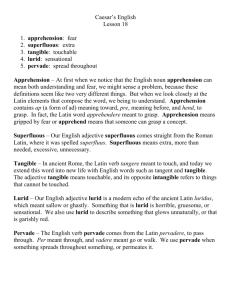

COMMUNICATION APPREHENSION IN THE WORKPLACE AND

advertisement