Current Issues

Public debt in 2020:

International topics

July 6, 2011

Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

The global crisis has caused a massive fiscal deterioration and

resulted in a sharp increase in developed market (DM) economies’

public indebtedness. On a GDP-weighted average, the DM public-debt-to-GDP

ratio climbed to around 104% in 2010 from roughly 77% in 2007. While the

troubled EMU peripheral countries have been pressured by markets to start

consolidating drastically, other DMs such as the US or Japan have continued to

run highly expansionary fiscal policies despite rapidly growing debt.

In our baseline scenario, which assumes a gradual tightening of fiscal

policies, the DM public debt stock is projected to rise to around 126%

of GDP in 2020 from roughly 104% in 2010. However, should fiscal

consolidation fail, public indebtedness could soar to more than 150% of GDP by

2020, according to our “no-policy-change” scenario. But also in the event of lower

growth, weaker fiscal accounts and/or higher market interest rates, the DM public

debt ratio could rise more sharply than sketched in our baseline scenario.

Fiscal policies have become unsustainable not only in a couple of

smaller EMU countries but also in some major DM economies. Many

DM economies are at the moment nowhere near short-term debt stabilisation.

Therefore, lowering debt ratios to pre-crisis or prudential levels will require a

prolonged consolidation process and thus strong political support and stamina.

Apart from the EMU peripheral countries the debt outlook for the US

is particularly worrying. If US policymakers fail to agree on a more drastic

Authors

Sebastian Becker

+49 69 910-30664

sebastian.becker@db.com

Wolf von Rotberg

+49 69 910-31886

wolf-von.rotberg@db.com

consolidation programme than presumed in our baseline scenario, the US debt

stock may climb to around 134% of GDP by 2020. As a result, the debt interest

burden could rise considerably over time and thus increasingly weigh on sovereign

creditworthiness. S&P‟s recent move to attach a negative outlook to the US

sovereign AAA long-term credit rating was a warning shot which deserves to be

taken seriously.

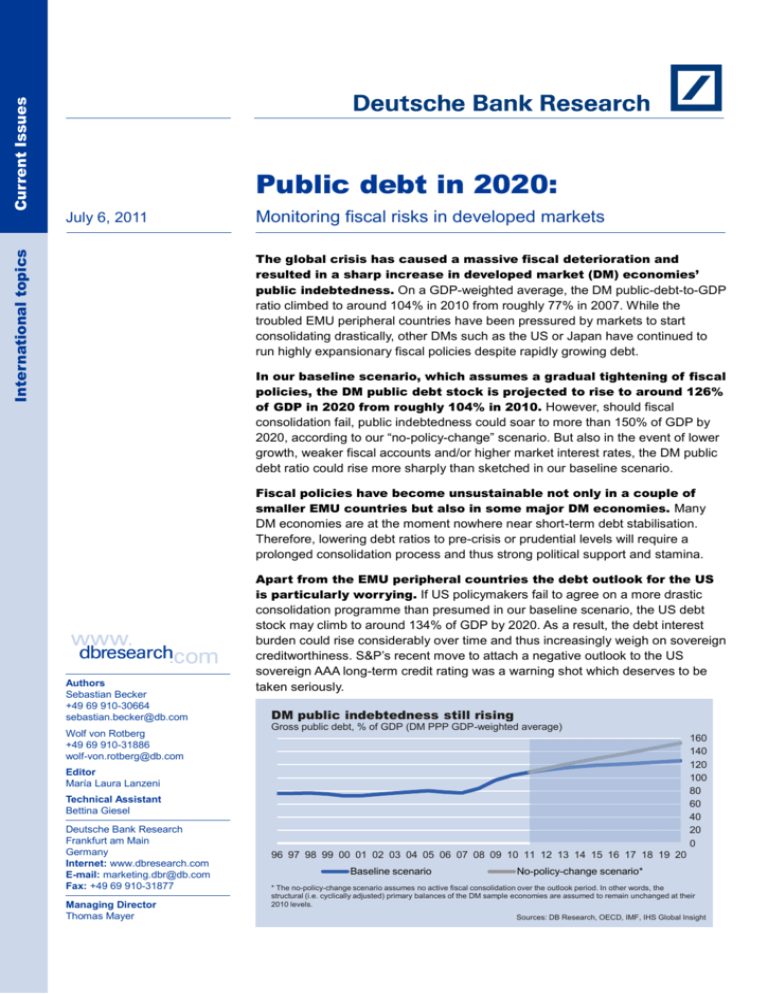

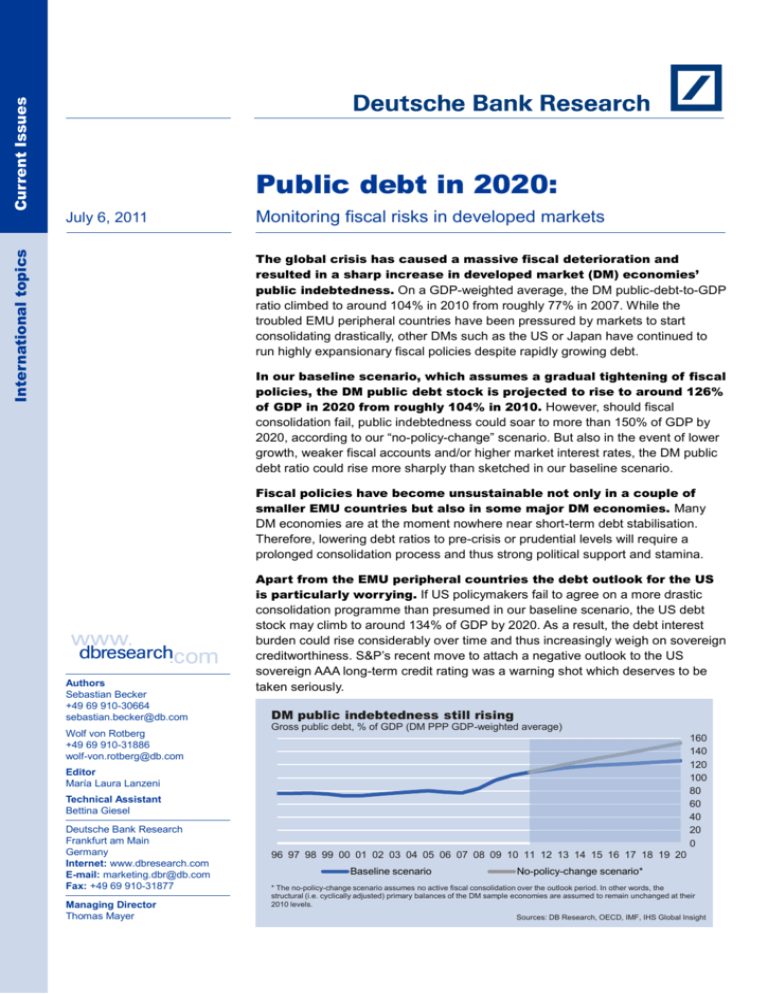

DM public indebtedness still rising

Gross public debt, % of GDP (DM PPP GDP-weighted average)

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

Editor

María Laura Lanzeni

Technical Assistant

Bettina Giesel

Deutsche Bank Research

Frankfurt am Main

Germany

Internet: www.dbresearch.com

E-mail: marketing.dbr@db.com

Fax: +49 69 910-31877

Managing Director

Thomas Mayer

96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Baseline scenario

No-policy-change scenario*

* The no-policy-change scenario assumes no active fiscal consolidation over the outlook period. In other words, the

structural (i.e. cyclically adjusted) primary balances of the DM sample economies are assumed to remain unchanged at their

2010 levels.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global Insight

Current Issues

Contents

Page

1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 3

2. Why the public debt structure matters ........................................................................................................ 4

2.1. A look at the public debt structure ......................................................................................................... 4

Public debt by currency denomination .................................................................................................. 4

Average maturity of public debt ............................................................................................................. 5

Public debt by type of interest-rate contract .......................................................................................... 6

Public debt by residency of holder ........................................................................................................ 7

2.2. Public debt risk matrix ........................................................................................................................... 8

Box 1: Our new public debt scenario framework ......................................................................................... 11

3. Public debt scenario analysis ..................................................................................................................... 13

3.1. Scenario framework and methodology ................................................................................................ 13

3.2. Baseline scenario ................................................................................................................................ 15

Macroeconomic and financial market assumptions ............................................................................ 15

Public-debt-to-GDP projections ........................................................................................................... 20

3.3. Shock scenarios .................................................................................................................................. 22

Shock scenario methodology .............................................................................................................. 22

Public-debt-to-GDP projections in a shock scenario ........................................................................... 23

(a) Single real GDP growth shock scenario .................................................................................... 23

(b) Single primary balance shock scenario ..................................................................................... 23

(c) Single market interest rate shock scenario ................................................................................ 24

(d) Contingent liability shock scenario ............................................................................................. 25

(e/f) First and second combined shock scenarios ........................................................................... 26

Summary of pessimistic shock scenarios ............................................................................................ 26

Optimistic shock scenarios .................................................................................................................. 27

Box 2: Calculating fiscal consolidation needs .............................................................................................. 28

4. Fiscal consolidation needs ......................................................................................................................... 29

4.1. Stabilising debt ratios at 2010 levels ................................................................................................... 29

4.2. Lowering debt ratios to pre-crisis levels .............................................................................................. 31

4.3. Lowering debt ratios to prudential benchmarks................................................................................... 32

5. Summary and conclusions ......................................................................................................................... 33

Literature ........................................................................................................................................................... 35

2

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

1. Introduction

Global crisis has caused

sharp fiscal deterioration

This study is a follow-up to our research paper “Public debt in 2020:

A sustainability analysis for DM and EM economies” (see Becker et

al. (2010)), which was published just before the EMU sovereign debt

crisis escalated in spring 2010 and which projected public debt

dynamics until the year 2020 for a sample of 38 economies,

consisting of 17 developed market (DM) and 21 emerging market

(EM) economies. The main finding was that public debt sustainability

had become a serious challenge to the advanced world. Equipped

with updated figures, the main aim of this paper is to re-estimate our

debt projections for the DM sample (see all 17 DM country names in

chart 1).

Fiscal deficit, % of GDP

IE

GR

US

GB

PT

ES

JP

FR

SK

IT

BE

AU

CA

DE

DK

SE

CH

DM*

-5

0

5

2000-06 (average)

10

15

2007-10 (average)

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF

1

DM public debt up sharply

DM gross public debt, % of GDP

110

100

90

80

70

60

94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10

PPP GDP-weighted average

Simple average

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global

Insight

2

Sovereign risk repriced

since 2008!

5-year sovereign CDS, bp

The paper is structured as follows. In Chapter 2 we take an in-depth

look at the composition of public debt, as the current crisis has

demonstrated that not only the debt level or the fiscal balance but

also a government‟s debt structure determine a country‟s

vulnerability to crisis. We construct a public debt risk matrix that

ranks countries with respect to the risks stemming from debt levels

as well as from debt structures. In Chapter 3 we use our new

scenario framework, which explicitly takes a government‟s debt

structure into account, to project public debt dynamics over the next

ten years. In the baseline scenario we assume a policy of fiscal

consolidation, with the consolidation pace varying across countries.

In the “no-policy-change” scenario we project the debt levels that

could be reached by 2020 in the absence of consolidation.

Moreover, we calculate “shock” scenarios which are characterised

by a more challenging economic and financial environment, as e.g.

by lower GDP growth or higher market interest rates. In Chapter 4

we estimate how much consolidation is needed to (a) stabilise debt

stocks at current levels and (b) lower debt ratios to pre-crisis levels,

or levels considered “prudent”. Chapter 5 concludes.

GR

IE

PT

ES

IT

FR

JP

DE

GB

US

2,250

2,000

1,750

1,500

1,250

1,000

750

500

250

0

Indeed, the global crisis has caused a massive fiscal deterioration in

many DM economies (see chart 1) and led to a drastic increase in

public indebtedness. On a GDP-weighted average, the DM publicdebt-to-GDP ratio climbed sharply to around 104% in 2010 from

around 77% of GDP in 2007, a jump of more than 25% of GDP in

just three years (see chart 2). Against the backdrop of growing debt

sustainability concerns, financial markets have sharply repriced

sovereign credit risks in many DM economies, as reflected by

widening sovereign CDS spreads (see chart 3). Especially in the

troubled EMU peripherals Greece, Ireland and Portugal, all of which

had to seek EU/IMF aid, sovereign CDS spreads have remained

close to or even at all-time highs (see chart 3), indicating that

financial markets attach a high probability to a debt restructuring

scenario. However, public finances have become unsustainable not

only in these smaller EMU peripheral countries but also in some

major advanced economies. In the US and Japan, for instance,

governments have continued to post large fiscal deficits despite

already large and growing debt stocks. By contrast, other major

DMs, such as the UK, have already begun consolidating to prevent

public debt spinning out of control.

January 2008 (eop)

Peak (since January 2008)

June 2011

Sources: Bloomberg, Markit, DB Research

July 6, 2011

3

3

Current Issues

2. Why the public debt structure matters

Sovereign CDS: Blown

out in EMU peripherals,

up modestly in Japan

5-year sovereign CDS, bp

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

0

07

08

09

GR

10

11

IE

PT

JP

4

Source: Bloomberg

It's not only the government

debt level that matters for

sovereign risk perception

Gross public debt, % of GDP

225

200

175

150

125

100

75

PT

The foreign currency exposure is paramount among risks inherent in

the debt structure because of the material debt reset effects local

currency devaluations could have on the public-debt-to-GDP ratio.

Rapid and unexpected devaluations repeatedly caused severe

distress or default in EMs, as for instance in the Argentinian crisis of

2001/2002 (see “The Argentinian crisis of 2001/02” in the box on

page 5). As most DMs are home to internationally accepted reserve

currencies they enjoy a major advantage over most EMs. They

neither need to peg their currencies to a stronger foreign currency

nor do they have to issue foreign currency (FCY) debt. Thus, the

potentially most severe single market risk factor to a country‟s public

debt stock, a rapid and unexpected exchange-rate movement, is

only of minor concern for most DMs.

JP

5

Public debt vs. sovereign

CDS spreads

X: Gross public debt, % of GDP (2010),

Y: Sovereign CDS spread, bp (June 2011)

2,500

GR

2,000

1,500

1,000

IE

500

ES

IT

AU

JP

50

100

150

200

This analysis is based on our DM sample, which

consists of 17 DM economies.

Sources: OECD, Bloomberg, Markit, DB Research

In our DM sample only Sweden, Denmark and Canada have issued

significant shares of public debt in foreign currencies (see chart 7 on

page 5). Unlike other countries in our sample, their currencies are

not considered international reserve currencies. Higher market

liquidity in reserve currency markets may be one of the reasons to

1

search for funding in major currencies.

In Sweden, where a foreign currency share of 15% is targeted, FCY

government debt accounted for around 14% of total public debt in

2010. Since the onset of the global financial crisis, the Danish

government increased its amount of outstanding FCY debt to 11.8%

0

0

6

1

4

A look at the public debt structure

25

Sources: OECD, IHS Global Insight

PT

2.1

Public debt by currency denomination

90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10

IE

Even in a sample of developed markets with relatively similar

macroeconomic characteristics, sovereign CDS do not always trade

in line with public debt levels (see chart 6). A likely explanation for

this apparent disconnect is that, when assessing default risks,

markets consider not only the level of public debt but also its

structure. In this chapter we take a closer look at the debt stocks of

DM economies. We analyse the debt structure and show debt

composition by currency denomination (local vs. foreign), by

maturity (short vs. long term), by type of interest-rate contracts

(fixed, floating, inflation-linked) and by residency of creditors

(internal vs. external). In a second step, we develop a public-debt

risk matrix, which ranks countries according to their solvency and

debt structure indicators.

50

0

GR

Even though higher indebtedness tends to make countries more

vulnerable to economic and financial turmoil, CDS and bond

spreads suggest that the debt level is far from being the only

determinant of a country‟s implied probability of default. Sovereign

credit ratings or CDS spreads, which signal the implied probability of

default on public debt, are only loosely correlated with the publicdebt-to-GDP ratio. Structural indicators for potential market demand

and the debt stock‟s shock resilience also play a role. Contrary to

highly indebted Japan for example, Greece, Ireland and Portugal

have been confronted with severe market pressures despite much

lower (albeit still large) debt ratios (see chart 4 and 5).

The larger number of market participants minimises bid-ask spreads and

correspondingly the interest rate or bond yield a government issuer has to offer.

Besides budget financing, governments may want to signal their commitment to an

existing currency peg. By tying the debt burden to the stability of the local

exchange rate they can increase the credibility of an existing currency peg.

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

The Argentinian crisis of 2001/02

In the case of Argentina‟s sovereign default in

the early 2000s, the government‟s high share

of FCY debt made the government debt

burden unbearable as soon as markets

started to doubt the credibility of the peso‟s

peg to the US dollar. The peg was abandoned

straight after sovereign default. One reason

for the loss of credibility was Argentina‟s weak

export performance (against the backdrop of

high import growth) and its related current

account deficits throughout the 1990s, which

led to rising external debt. Generally, a large

and competitive export sector is vital for a net

external (FCY) debtor country because it

generates hard-currency revenues and hence

secures the government‟s ability to honour its

FCY obligations. Overall, a country should

borrow only as much in foreign currencies as

its economy is able to generate and hence to

repay. In other words, currency mismatches

between the government‟s liablities and

revenues should be limited.

Public debt by currency

FCY debt, % of total public debt (2010)

SE

DK

CA

GR

ES

PT

CH

SK

BE

IT

14.0

11.8

3.5

1.9

1.5

1.3

0.6

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

5

10

15

Sources: National sources, OECD, Bloomberg,

DB Research

7

US short-term rates still

way below long-term rates

%

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

07

08

09

10

11

Fed funds target rate

3-month US T-Bill yield

10-year US Treasury yield

Sources: IHS Global Insight, DB Research

8

of total general government debt in 2010. Besides direct euro

purchases, FCY debt issuance was used as an instrument to

enlarge the central bank‟s foreign currency reserve holdings,

material to the stability of the krona‟s narrow peg to the euro. In

Canada, FCY debt accounted for 3.5% of general government debt

in 2010. Most of Canada‟s foreign currency funding is met through

foreign currency swaps. In 2009, however, for the first time in a

decade the Canadian DMO issued two foreign currency bonds. The

proceeds of the USD 3 bn and EUR 2 bn issues were exclusively

used to increase Canada‟s foreign exchange reserves. Given that

Sweden, Denmark and Canada are home to large and competitive

export industries, a gradual depreciation of their currencies would be

unlikely to lead to a large increase in their public-debt-to-GDP

2

ratios. This is a major difference to the risks found in some EM

economies (for a detailed discussion on currency mismatches in EM

countries see for instance Becker (2011) page 8).

Average maturity of public debt

The nominal interest rate which a government effectively pays on its

public debt is not only determined by prevailing market interest rates

but also by the pace at which changing market conditions affect

coupon payments on outstanding government securities. The

market interest rate is determined by the official policy rate, which is

set by the central bank, inflation expectations as well as the default

risk premium demanded by investors. The share of debt that adjusts

to new market conditions depends on the amount of variableinterest-rate and inflation-linked debt as well as on the amount of

maturing fixed-interest-rate debt that needs to be rolled over at

market interest rates. Increased short-term debt issuance can

significantly reduce a government‟s effective interest rate. However,

over-reliance on short-term debt poses significant roll-over risks and

leaves a sovereign exposed to rising market interest rates.

A shift towards short-term debt is generally observed at times of

crisis. The reason is twofold. First, short-term borrowing becomes

relatively cheaper than long-term borrowing thanks to crisis-induced

monetary policy easing (see chart 8). Second, short-term debt

markets become much easier to tap for most debtors during periods

of stress than longer-term markets, especially for those borrowers

with relatively poor credit standings. Long-term yields react less

sensitively to interest rate cuts by central banks due to a variety of

factors. Future growth and inflation expectations tend to be higher

and the default risk premium usually rises with the length of a debt

instrument‟s maturity. Furthermore, if a country faces severe market

pressure, increased short-term borrowing itself may cause long-term

yields to rise because short-term debt holders are more likely to be

repaid than long-term debt holders. The combined effect is a

considerable steepening of the yield curve, making short-term debt

even more attractive to long-term debt.

De Broeck and Guscina (2011) find that the share of short-term debt

issuance in total debt issuance from the second half of 2008 to the

end of 2009 increased in 11 out of 16 EMU sovereigns compared to

the 1 ½-year pre-crisis period. In Belgium, for example, the share of

T-bills in total debt issuance increased to 50.7% from 21.3%. Ireland

did not issue T-bills at all in the 1 ½ years before the crisis.

2

July 6, 2011

In Sweden, for instance, where the local currency depreciated by 15% in 2009 as

a result of the financial crisis, the rise in the public-debt-to-GDP ratio remained

manageable and the country became one of the fastest growing DM economies in

2010, partly thanks to local currency depreciation and strong export performance.

5

Current Issues

Public debt by maturity

Average maturity, years (2010)

16

13.4

14

12

10

7.8

8

7.2

7.2

7.1

6.9

6.8

6.7

6.5

6.3

6.3

6.2

5.9

5.8

5.7

PT

JP

6

4.9

4.7

AU

US

4

2

0

GB

DK

IT

FR

GR

CH

IE

ES

BE

DE

SK

SE

CA

Sources: National sources, OECD, Bloomberg, DB Research

Public debt by type of

interest-rate contract

However, from the second half of 2008 to the end of 2009 the share

of short-term to total debt issues stood at 47.4%. At the end of 2010

the US (4.7 years), Australia (4.9 years) and Japan (5.7 years) had

the shortest average maturities among our sample economies, while

the UK (13.4 years), Denmark (7.8 years) and Italy (7.2 years) had

the longest average maturities (see chart 9). In Greece, the average

maturity shortened over recent years, from 8.5 years in 2007 to

around 7.1 years at the end of 2010. Over the course of 2010 more

than ¾ of Greek issues were T-bills with maturities of below one

year.

% of total public debt (2010)

GR

GB

SE

IT

FR

SK

AU

Public debt by type of interest-rate contract

US

JP

CA

IE

DE

DK

BE

ES

PT

CH

0

20

40

60

80

100

Fixed-interest-rate debt

Floating-interest-rate debt

Inflation-linked debt

10

Sources: National sources, OECD, DB Research

UST inflation-linked debt

share has shrunk

UST inflation-indexed notes and bonds

12

700

600

10

500

8

400

6

300

4

200

2

100

0

0

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

USD bn (right)

% of total* (left)

* gross marketable, interest-bearing UST debt.

Sources: IHS Global Insight, US Treasury

6

9

11

Investor preferences can have a major effect on a country‟s debt

structure. For example, in the UK Gilt market, domestic pension

funds and insurance companies play an important role, as reflected

by the 28% share they hold in the outstanding Gilt market. In order

to match their liability structure they demand long-term, inflationlinked assets. The British debt management office (DMO) is meeting

those demands. It was the first DMO that issued inflation-linked

securities. The purchase of the first linkers in the early 1980s was

restricted to domestic pension funds. It was not a coincidence that

they were issued after a prolonged period of high inflation. Tying the

interest expenditure to inflation was designed to make inflationary

policies less desirable for a government and hence dispel inflation

worries of long-term investors. In 2010 around 22% of outstanding

UK Gilts were linked to the domestic inflation rate, with maturities of

10 years and more (see chart 10). The largest inflation-linked market

worldwide, however, is the US Treasury Inflation Protected

Securities (TIPS) market. With a volume of more than USD 600 bn,

TIPS account for a significant share of total US Treasury (UST) debt

(see chart 11).

Elsewhere in Europe, Sweden was the first country to issue

inflation-linked bonds in 1994. The Swedish DMO targets a constant

inflation-linked debt share of 25% of total debt. Right now 20% of

outstanding debt is linked to domestic inflation, according to the

Swedish DMO. Insurance companies and pension funds, as in the

UK, are the dominant investor groups in the Swedish inflation-linked

government bond market. They hold more than two-thirds of

Swedish inflation-protected debt. France issued its first inflationindexed bonds in 1998. Driven by low inflation rates, the share of

French inflation-protected debt issuance fell to 7.5% of total

issuance in 2009, the lowest level since 2001. For 2010 the French

DMO set a target of 10% of total issuance, reflecting the increasing

demand for inflation-hedged instruments after the crisis. A similar

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

observation could be made in several DMs. In the US, for instance,

the inflation-linked debt share shrank to around 7% of gross

marketable interest-bearing UST debt from more than 10% in

2007/08 (see chart 11 and 12), presumably driven by subdued US

inflation expectations in the aftermath of the crisis, evidenced by an

almost closed spread of 10-year UST yields over 10-year US TIPS

yields in late 2008/early 2009 (see chart 13). However, rising

inflation expectations are likely to boost demand for DM inflationprotected government debt again (see Blommestein, 2011). This

development can be regarded as favourable with respect to

governments‟ incentives to decrease their debt stocks by accepting

higher inflation rates.

Inflation-linked public debt

of selected DM countries

% of total public debt

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10

US

FR

GB

GR

AU

SE

Sources: National sources, OECD, DB Research

Public debt by residency of holder

To minimise risks, a DMO should preferably issue domesticcurrency-denominated, fixed-interest-rate government securities

with long maturities to a strongly committed creditor group. A strong

and affluent domestic funding base proved valuable for several

highly-indebted sovereigns in the past. In this regard, the Japanese

creditor structure is outstanding. Even though the gross government

debt level currently stands at around 200% of GDP, the annual fiscal

deficit is forecast to remain above 7% of GDP until 2013 and real

GDP growth has averaged only 0.7% p.a. since 1997 (which makes

future fiscal consolidation very challenging), 10-year Japanese

government bonds (JGB) yielded less than 1.2% in June 2011. The

Japanese government enjoys the advantage that it can resort to a

cash-rich domestic population which gladly finances its fiscal

deficits. At 376% of disposable income in 2009, Japanese

households‟ net financial wealth was higher than in any other large

DM country. The deep pool of domestic savings and the large

publicly-owned financial sector provide a very strong and reliant

funding base. More than 90% of general government debt is held by

Japanese domestic investors and more than 50% was held by the

3

broader public sector in 2009.

12

US bond yields point to

mild inflation expectations

%

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

07

08

09

10

11

10-year US Treasury yield

10-year US TIPS yield

10-year UST yield minus TIPS yield, pp.

Sources: IHS Global Insight, DB Research

13

The resilience of Japanese debt has repeatedly been demonstrated.

Neither the March earthquake and its economic impact, nor

repeated rating downgrades by major rating agencies put upward

pressure on JGB yields. Although an internationally diversified

creditor structure minimises direct domestic spill-over effects from

one sector to another and presence in international markets

increases liquidity, close ties with a rich and only moderately

leveraged domestic financial sector may be crucial to fund the

government in times of distress.

Public debt by holder

External debt, % of total public debt (2010)

70

67

54

60

50

39

40

30

25

26

28

28

29

GB

SK

AU

SE

DK

32

US

43

59

59

61

BE

PT

IE

47

18

20

7

8

JP

CH

10

0

CA

IT

ES

DE

FR

Sources: National sources, JEDH, DB Research

3

July 6, 2011

GR

14

See Fitch (2010), p. 1.

7

Current Issues

External UST debt has risen

over the past decade ...

UST securities held at the Federal

Reserve Banks by foreigners

35

3.0

30

2.5

25

2.0

20

1.5

15

1.0

10

0.5

5

0

0.0

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

USD tr (right)

% of gross marketable debt (left)

% of gross total debt (left)

Sources: IHS Global Insight, US Treasury, Fed

15

Large UST purchases by

foreigners, lower US yields

10

10

8

15

6

20

4

25

2

30

90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10

10-year US Treasury yield, % (left)

US Treasury securities held by

foreigners, %* (inverted scale, right)

* of total UST gross marketable debt.

Sources: IHS Global Insight, Fed, DB Research

16

The European countries with notorious current account deficits,

Greece and Portugal, as well as Ireland, mostly relied on financing

from foreign creditors in the past. As shown in chart 14 on page 7,

public-external debt accounted for 67%, 61% and 59% of total debt

4

in Greece, Ireland and Portugal, respectively, by the end of 2010. In

the above three countries external funding ran dry in 2010/11 and

could not be offset by the respective domestic financial sectors.

These governments ultimately required external help in the form of

EU/IMF-led bail-out programmes.

The US is a special case in terms of foreign debt holdings and

vulnerability. Different to Japan, a large share of US government

debt is held by foreign creditors and different to peripheral European

countries, it is unlikely that the US will experience a sudden stop of

external funding due to its systemic importance for the global

economy. The amount of UST debt held by non-residents has risen

noticeably over the past decade to around 18% of total (or 29% of

marketable) UST debt in April 2011, from just 11% (20%) in early

2000 (see chart 15), mainly as a result of large UST purchases by

Asian countries, especially Japan and China. Rising foreign

participation in the US government bond market seems to have

contributed to the gradual fall in UST yields over recent decades and

years (see chart 16). Moreover, liquidity or roll-over risks arising

from the large Asian holdings of UST are probably contained, given

that an abrupt sale of these holdings would lead to significant losses

for Asian investors.

Other economies with relatively high public-external debt shares are

Belgium (59%) and France (54%) (see chart 14 on page 7). Highly

indebted Italy can be found together with Spain and the US in the

mid-range of our sample economies with external debt shares of

between 30% and 45% of total public debt in 2010. Overall, the

ongoing EMU sovereign debt crisis suggests that a well-funded

domestic investor base provides a strong backstop if liquidity and/or

solvency concerns about a government arise. However, stretching

the capacity of this backstop too far could result in even higher

losses if distress eventually occurs at a later point in time.

2.2

Public debt risk matrix

As explained in the previous sections, not only solvency indicators

but also the structure of public debt determine a country‟s

vulnerability to sovereign debt crisis. In order to gauge which of the

17 economies of our DM sample are the most/least vulnerable to

sovereign debt crisis we construct a public debt risk matrix which is

based on two different kinds of risk indicators.

The first indicator, the debt-structure indicator, captures the risks

inherent in a country‟s public debt structure, i.e. it indicates how

vulnerable a country is with respect to market and liquidity risks. It

reflects reliance on external creditors, the average maturity of public

debt outstanding, as well as the shares of floating-interest-rate and

inflation-linked debt in total debt. A country with relatively large

public external debt, a short average maturity as well as a high

share of variable-interest-rate and inflation-protected debt would

obtain a relatively poor score. On the contrary, a country with low

reliance on external debt, a long average maturity as well as no or

little floating-interest-rate and inflation-linked debt would receive a

4

8

External debt statistics record debt liabilities at market values. Due to significant

changes in the market value of Greek, Portuguese and Irish outstanding debt in

2010, we adjusted their respective nominal external debt values accordingly. See

Anderson, Jeffrey and Jared Bebee (2011).

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

Japan had by far the largest

public debt stock in 2010

% of GDP (2010)

AU

SK

relatively good score. The debt-structure indicator has a scale

between 1 and 17, with 1 being the best and 17 being the worst

score. The largest weight was given to the external debt share,

followed by the average maturity and the share of variable-interestrate and inflation-protected debt.

The second indicator, the debt level and dynamics indicator,

captures standard solvency indicators such as a government‟s debt

level and contingent liabilities from the banking sector (see chart 17)

as well as the primary balance and net debt interest payments (see

chart 18). Again, the indicator has a scale from 1 (best) to 17

(worst).

CH

SE

DK

CA

ES

DE

According to our public debt risk matrix (see chart 19), Greece

appears to be the most vulnerable country as it scores poorly with

respect to both indicators. At the other end of the spectrum,

Switzerland and Denmark are the least vulnerable countries. Other

relatively risky countries are Portugal, Ireland and the US. For the

US there are a couple of important risk mitigants, however, which

are not quantifiable and thus not captured in our simple indicatorbased approach. For instance, the US dollar‟s reserve currency

status or the generally high flexiblity of the US economy somewhat

reduce its vulnerability to a public debt crisis.

US

FR

BE

GB

PT

IT

GR

IE

JP

0

50

100

150

200

250

Gross public debt

Contingent liabilities

* Contingent liabilities from the banking sector are

DBR estimates based on IFS data and gross

problematic assets (GPA) estimates by S&P's.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, S&P's, IFS

17

Ireland had the widest

fiscal deficit in 2010

Fiscal deficit (2010) by sub-components,

% of GDP

IE

Japan appears to be less vulnerable than any of the three EMU

peripheral countries thanks to a relatively safe debt structure as e.g.

characterised by a very low external debt share. But also based on

the debt level and dynamics indicator, Japan is doing better than

Greece, Portugal and Ireland (see chart 19). Although Japan had by

far the largest gross public debt stock at almost 200% of GDP in

2010, its contingent liabilites from the banking sector appear to be

much lower than in, for instance, Greece, Ireland and Portugal (see

chart 17). Moreover, against the backdrop of large government

assets, such as the BoJ‟s sizable foreign exchange reserves,

Japan‟s net government debt stood at around 116% of GDP in 2010

and hence was much lower than gross government debt (see chart

20 on page 10).

US

GR

Public debt risk matrix

GB

Average ranking of countries: From 1 (best) to 17 (worst)

ES

16

PT

JP

JP IT

SK

FR

GR

14

IE

12

USA

GB

FR

AU

BE

10

ES

CA

CA

DE

IT

8

BE

6

DK

DE

SK

4

DK

AU

CH

SE

SE

2

CH

-5

0

5

Source: OECD

July 6, 2011

0

10 15 20 25 30 35

0

Net debt interest payments

Primary deficit

Debt level and dynamics indicator

PT

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Debt-structure indicator

18

Source: DB Research

19

9

Current Issues

Furthermore, despite its extremely large gross public debt stock the

Japanese government still has one of the lowest net debt interest

expenses thanks to a combination of very low nominal effective

interest rates it has to pay on gross debt as well as significant

interest income it receives on public assets. While Japan‟s gross

government interest expenses stood at around 2.8% of GDP in

2010, its net debt interest payments accounted for a much lower

1.4% of GDP and hence was just half of gross interest expenditures

in 2010 (see chart 21).

Japan has the largest

public debt stock ...

Public debt, % of GDP (2010)

SE

DK

CH

AU

SK

Although our public debt risk matrix is able to indicate which of our

17 sample economies are the countries most/least prone to

imminent debt crisis, it does not say anything about a country‟s

absolute risk level to run into sovereign debt problems over the

medium to long term. In the next two chapters we will therefore

address the question of which countries are doing well in terms of

medium to long-term public debt sustainability and which countries

could run into debt problems at a later point if they failed to

consolidate.

CA

ES

DE

GB

FR

IE

US

PT

BE

IT

GR

JP

-50

0

50

100

Gross

150

200

Net

Source: OECD

20

... but one of the lowest

levels of net debt interest

payments

Debt interest payments (2010), % of GDP

SE

CH

DK

CA

SK

AU

JP

ES

US

DE

FR

IE

GB

PT

BE

IT

GR

0

1

2

Gross

3

4

5

Sources: OECD, IHS Global Insight

10

6

Net

21

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

Box 1: Our new public debt scenario framework

In Becker et al. (2010), “Public debt in 2020: A sustainability analysis for DM and EM economies”, we based

our public debt sustainability framework on the basic concept of public debt arithmetics, which required

assumptions on real GDP growth, the primary balance and the real interest rate. The average real interest rate

paid on public debt is difficult to calculate because of a heterogeneous debt structure. Usually a government

has outstanding debt and also continuously issues new debt at different maturities (short/medium vs. long-term

debt), in different currencies (domestic vs. foreign debt) and/or at different types of interest-rate contracts

(fixed, floating vs. inflation-linked debt). As a result, there is no single interest rate that represents a

government‟s ultimate borrowing costs. While Becker et al. (2010) approximated a government‟s relevant real

interest rate via the prevailing CPI-deflated benchmark government bond yield, we now introduce a new

framework which explicitly models a sovereign‟s average real interest rates paid on public debt, taking into

account the structure of that debt.

Our new debt sustainability framework is derived from Ley (2005) and based on Becker (2011), who describes

public debt dynamics in a two currency (domestic vs. foreign)/two sector (non-tradable vs. tradable GDP)

framework that explicitly differentiates between the contractual type of interest rates (fixed vs. floating) and the

structure of local-currency-denominated debt (straight vs. inflation-protected debt) and considers the average

maturity of a country‟s public debt stock. Most DM economies issue the bulk of their public debt in domestic

currency, so DM public debt stocks are generally unaffected by debt reset effects stemming from currency

fluctuations. Therefore, we simplify Becker‟s two currency/two sector framework into a single currency/single

sector public debt sustainability model.

1.

Public debt dynamics

The starting point of our analysis is the ex-post period budget constraint of the government:

dt

1 i

eff ,t

1 gt 1 t

d t 1 pbt mt

(1)

where d denotes the public-debt-to-GDP ratio, ieff captures the nominal effective interest rate paid on public

debt outstanding, g and π stand for the real GDP growth rate and the change in the GDP deflator (which is in

the following approximated by domestic inflation) and pb and Δm represent the primary balance (i.e. the fiscal

balance before net debt interest payments) and seigniorage (i.e. the change in the base-money-supply-to-GDP

ratio), respectively. Finally, t denotes the respective year of each variable.

As apparent from equation (1), the current public-debt-to-GDP ratio depends on the debt stock of the previous

year as well as on the current macroeconomic and financial environment and public finances. Generally, strong

real GDP growth and a positive change in the GDP deflator (i.e. positive inflation), a low nominal effective

interest rate and sound fiscal policies (as reflected by primary surpluses) are prerequisites to keep public debt

dynamics in check.

2.

Nominal effective interest rates

The nominal effective interest rate paid on public debt is determined by a host of factors such as the prevailing

market interest rates, the average maturity of the debt stock (which determines how quickly changes in market

interest rates affect the nominal effective interest rate) as well as the domestic inflation rate. As the

composition of debt plays a crucial role in the determination of the nominal effective interest rate, one needs to

differentiate between the contractual type of interest payments (floating, fixed, inflation-linked), and also needs

to consider the average maturity of outstanding debt.

July 6, 2011

11

Current Issues

The nominal effective interest rate (ieff) can be expressed as:

ieff ,t iˆeff ,t t 1 ieffh,,t

Weighted nominal

effective interest

rate before inflation

compensation

where

(2)

Inflation

compensation

costs on CPIlinked debt

h,x

is the share of inflation-protected debt to total debt, is the domestic inflation rate and ieff

is the

effective base (i.e. “real”) interest rate component paid on inflation-linked debt. As apparent from equation (2),

the higher the share of inflation-protected debt to total debt (Х) the higher the inflation-related compensation

costs on inflation-protected debt (in the case of a positive inflation rate).

The weighted nominal effective interest rate before inflation compensation costs is given by:

iˆeff ,t 1 ieffh,1,t ieffh,,t

Interest rate

component on noninflation-linked debt

(3)

Base (i.e. “real“) interest

rate component on

inflation-linked debt

As shown in equation (3), the weighted nominal effective interest rate before inflation compensation costs

h, x

hinges on (a) the effective base interest rate component on inflation-protected debt ( ieff

) and the nominal

h ,1 x

effective interest rate on non-inflation-protected debt ( ieff

) debt and, on (b) the shares of inflation-protected

(Х) and straight debt (1-Х) to total debt.

h, x

h ,1 x

Finally, let us show how the above-mentioned effective interest rates ( ieff

, ieff

) are determined, i.e. how

quickly they adjust to changes in market interest rates.

The individual effective interest rate that is paid on the different slices of debt (i.e. on non-inflation-linked as

well as inflation-linked debt) is given by:

ieffj ,t p it (1 p) ieffj ,t 1

j

(4)

where:

j h,1 ; h,

p

(5)

As shown in equation (4), the effective interest rate on the different slices of debt is the weighted average of

j

j

the prevailing market interest rate ( it ) and the effective interest rate of the previous year ( i eff ,t 1 ). As also

apparent from equation (4), the higher the share of debt that is (on average per year) subject to new financial

market conditions (p) the more sensitively the effective interest rate reacts to changing financial market

1

conditions. Moreover, as shown in equation (5) , the share of debt that adjusts on average per year to new

market conditions (p) depends on both the share of floating-rate-debt in total debt (ω) and the share of debt

that has to be rolled-over per year (μ), which is given by the reciprocal value of the average maturity of

outstanding debt. As part of floating-interest-rate-debt has to be rolled over each year anyway, we have to

subtract the cross-product of μ and ω in order to avoid double-counting.

____________________

1

Equation (5) applies to non-inflation-protected debt only. In the case of inflation-linked debt, the share of debt that adjusts to new market

interest rates is solely given by μ as there is generally no floating-interest rate component on inflation-protected debt.

12

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

3.

Debt scenario analysis

By plugging equation (2) into equation (1), we obtain the following expression:

Weighted nominal effective

interest rate before inflation

compensation

Inflation

compensation

costs on CPIlinked debt

1 iˆ 1 i h , x

eff ,t

t

eff ,t

d t 1 pbt mt

dt

(

1

g

)

(

1

)

t

t

Inflation benefits/

(6)

costs

As apparent from the right-hand side of equation (6) the current year‟s public-debt-to-GDP ratio depends on

the previous year‟s public-debt-to-GDP ratio, the current nominal effective interest rate, the current real GDP

growth rate, the current inflation rate, the current primary balance and current seigniorage. From equation (6)

we can now see that, ceteris paribus, there would be an increase (decrease) in the public-debt-to-GDP ratio by

the end of this period if (a) the real GDP growth rate decreases (increases), (b) the inflation rate decelerates

(accelerates), (c) the primary balance deteriorates (strenghtens) and/or (d) seigniorage decreases (increases).

As regards the direct effects of inflation on the public-debt-to-GDP ratio, the lower (higher) the share of

inflation-linked debt to total debt the more (less) a country‟s public-debt-to-GDP ratio falls, ceteris paribus,

when domestic inflation accelerates. On the one hand, a country which has 100% of its public debt outstanding

linked to the domestic inflation rate will not be able to lower the public-debt-to-GDP ratio via higher inflation. On

the other hand, a country which has no inflation-linked debt at all will benefit most significantly from a falling

public-debt-to-GDP ratio in the case of accelerating inflation. However, one should also bear in mind that

higher domestic inflation will most likely lead (either immediately or with a time lag) to “second-round” effects

such as a general rise in market interest rates as investors demand a larger inflation and/or risk premium. As

seen in (4) and (5) the shorter (longer) the average maturity of public debt outstanding, the stronger (weaker)

the adverse interest-rate effect. Moreover, in the event of an active inflationary monetary policy (that aims to

produce higher inflation rates to decrease the real value of public debt) one would also need to take the central

bank‟s seigniorage from printing more money into account when carrying out a cost-benefit analysis of higher

inflation.

Note: As regards our public debt sustainability scenario analysis presented in this chapter, we omitted

the seigniorage term (Δm) of equation (6) for simplicity.

3. Public debt scenario analysis

In this chapter we analyse public debt dynamics in the 17 DM

sample economies over the outlook period 2011-20. This analysis

gives an update to our public debt projections presented in previous

research (see “Public debt in 2020: A sustainability analysis for DM

and EM economies”).

3.1

Scenario framework and methodology

As discussed in the previous chapter, a favourable public debt

structure can be an important mitigant for sovereign debt risks. Vice

versa, a precarious debt structure can expose a country to high

market and roll-over risks. The following debt sustainability analysis

is based on our new scenario framework that explicitly models a

country‟s debt structure. For instance, our new framework considers

the average maturity of government debt as well as the proportion of

floating-interest-rate debt in total debt outstanding, and thus

implicitly accounts for the speed at which a sovereign‟s nominal

effective interest rate adjusts upwards to higher market interest

rates. Furthermore, our model takes the share of inflation-protected

debt to total debt into account, and hence is able to gauge the

July 6, 2011

13

Current Issues

ultimate effects of higher or lower inflation on the debt-to-GDP ratio.

For readers who are interested in the underlying framework, a

technical description is given in Box 1 on page 11-13.

Monetary expansion has

kept bond yields low

%

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

Fed funds target rate

10-year US Treasury yield

ECB refi rate

10-year Bund yield

Sources: IHS Global Insight, DB Research

22

Large credit stocks

increase contingent

liabilities for the sovereign

Private-sector credit, % of GDP (2010)

SK

US

JP

BE

GR

DE

AU

CA

IT

FR

SE

CH

GB

PT

ES

DK

IE

DM*

0

50

100 150 200 250 300

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, S&P's, IFS, IMF,

IHS Global Insight

14

23

In our baseline scenario we calculate possible outcomes for our DM

sample economies‟ public-debt-to-GDP ratios over the the next ten

years in the absence of major financial as well as real economic

shocks. In the baseline scenario fiscal consolidation is presumed to

advance gradually over the next ten years, with the pace of

consolidation varying across countries. We also assess DM public

debt dynamics in four adverse single-variable shock scenarios as

well as in two adverse combined shock scenarios.The aim of the

adverse shock scenario analysis is to obtain an idea of the levels

which public-debt-to-GDP ratios could reach in a more challenging

economic and financial market environment. In the single-shock

scenarios we consider (a) a real GDP growth shock, (b) a primary

balance shock, (c) a market interest rate shock, and (d) a contingent

liability shock in which the government is forced to provide financial

assistance to the banking sector. How should our adverse shock

scenarios be interpreted?

The single-shock scenarios serve as a sort of sensitivity analysis to

a country‟s public debt dynamics with regard to isolated deviations in

the underlying macroeconomic and financial variables from their

baseline numbers. In the growth shock scenario, for example, we

calculate a country‟s possible future debt path using lower real GDP

growth forecasts than in the baseline scenario but leaving the

forecasts for the remaining variables (i.e. inflation, market interest

rates, primary balance) unchanged.

Scenario (a) can be understood as a low-growth scenario in which

the economic activity is restricted by domestic and/or global factors

such as renewed global recession. Scenario (b) captures weakerthan-expected public finances which could arise from slumping

public revenue and/or rising primary expenditure, for instance,

driven by weaker-than-expected tax collection and/or higher social

government expenditures. In shock scenario (c) sovereign bond

yields, which have been relatively low over the past few years

thanks to weak growth, monetary expansion and subdued inflation

expectations (see chart 22), are assumed to rise sharply over the

outlook period. For instance, investors could become increasingly

concerned about long-term fiscal solvency and hence demand much

higher default risk premia on government securities. Furthermore,

bondholders could demand a much higher inflation risk premium as

they fear governments could opt to fight large public indebtedness

with higher inflation. Finally, in scenario (d) governments face

financial-sector bail-out costs as part of the banking sector assets

become problematic (see chart 23). Although the single-variable

shock scenarios are useful in revealing country-specific weaknesses

to certain shocks, it is more appropriate to assume that any shock

will affect most macroeconomic or financial variables at the same

time. To take account of such a scenario we conclude by running

two combined shock scenarios. In (e) the first combined shock

scenario we project public debt dynamics using lower real GDP

growth, a weaker primary balance, higher market interest rates as

well as higher consumer price inflation. While consumer price

inflation is assumed to decelerate in the first combined shock

scenario (deflationary world) due to large output gaps, it is assumed

to accelerate in (f) our second combined shock scenario because of

the lagged effects of abundant monetary liquidity and rising public

indebtedness.

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

3.2

Subdued growth prospects

Real GDP, % yoy

(DM PPP GDP-weighted average)

Macroeconomic and financial market assumptions

Before we turn to our updated public debt projections for the 17 DM

sample economies, we describe our baseline scenario assumptions

with respect to the key variables that are relevant for the future

evolution of a country‟s public-debt-to-GDP ratio. As apparent from

the right-hand side of equation (6) in Box 1 on page 13 we need to

make dynamic assumptions on a wide set of macroeconomic,

financial market and fiscal indicators in order to gauge future public

debt dynamics. In what follows, we briefly present our baseline

assumptions for real GDP growth, consumer price inflation, market

interest rates and the primary balance. Moreover, we explain how

we arrive at our nominal and real effective interest rate assumptions.

4

2

0

-2

-4

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20

Baseline

2000-09 average

Sources: DB Research, IMF

24

Real GDP growth (% p.a.)

For 2011-16 we take the IMF‟s real GDP growth forecasts (World

Economic Outlook Database, April 2011). For 2017-20 we assume

that our sample economies will grow at their potential, which is

approximated by the IMF‟s 2016 growth forecasts. Thus, the DM

GDP-weighted real GDP growth rate is assumed to average 2.3%

p.a. over the period 2011-20, somewhat higher than the 2000-09

ten-year historical average (see chart 24). Average DM growth over

the next ten years is expected to be only marginally higher than

projected in our study “Public debt in 2020: A sustainability analysis

for DM and EM economies”, published in March 2010. However, on

a single country basis, 2011-20 average growth rates deviate by a

couple of basis points, either positively or negatively, from previous

baseline projections (see chart 25).

Real economic growth

assumptions reviewed

Real GDP, % yoy (2011-20 average)

PT

IT

JP

GR

DE

ES

CH

BE

DK

FR

CA

GB

US

IE

AU

SE

SK

DM*

0

1

2

3

Baseline scenario

4

At the country level, Slovakia, Sweden and Australia are expected to

post the highest average growth over the next ten years at more

than 3% per year, while Portugal and Italy are forecast to grow

below 1.5% per year, the lowest rates in our country sample. Among

the three largest sample economies, the US economy is expected to

advance over the next ten years at a relatively robust average

growth rate of 2.7% per year, while real GDP growth is forecast to

be on average much weaker in Japan (+1.4% p.a.) and Germany

(+1.6% p.a.) (see chart 26).

5

Baseline assumptions ("Public debt in

2020", March 2010)

New baseline assumptions

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, IMF

25

Real GDP

% yoy

6

4

2

0

-2

-4

-6

PT

IT

JP

GR

DE

ES

Avg. 2000-09

CH

BE

DK

FR

CA

Avg. 2011-20

GB

US

IE

AU

SE

SK

DM*

2010

* DM PPP GDP-weighted series.

Sources: DB Research, IMF

July 6, 2011

26

15

Current Issues

Inflation

CPI (aop), % yoy

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

-2

JP

CH

GR

IE

PT

ES

US

FR

DE

Avg. 2000-09

DK

SE

IT

CA

BE

Avg. 2011-20

GB

AU

SK

DM*

2010

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, IMF

27

Market interest rates

10-year government bond yields, %

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

JP

DE

DK

SE

FR

US

SK

BE

Avg. 2000-09

CH

CA

IT

GB

ES

Avg. 2011-20

AU

IE

PT

GR

DM*

2010

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, IMF

28

Consumer price inflation (% p.a.)

Moderate inflation outlook

Inflation, % (DM PPP GDP-weighted avg.)

4

3

2

1

0

-1

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20

Baseline

2000-09 average

Sources: DB Research, IMF

29

Gov't bond yields to rise

10-year government bond yields, %

(DM PPP GDP-weighted average)

6

5

4

3

2

In line with our real economic growth assumptions we employ the

latest IMF consumer price inflation forecasts (World Economic

Outlook Database, April 2011) for the period 2011-16. Again, for

2017-20 a country‟s inflation rate is assumed to remain constant at

the IMF‟s 2016 forecast rate. Because of a moderate growth outlook

the DM GDP-weighted inflation rate is expected to average 1.8%

p.a. over the next ten years (see chart 27 and 29). Inflation is

projected to be the highest in Slovakia (2.9% p.a.) and Australia

(2.7% p.a.) and the lowest in Japan (0.7% p.a.).

Market interest rates (% p.a.)

We gauge a government‟s nominal market interest rate on non5

inflation-linked public debt , i.e. its prevailing borrowing costs in

financial markets, by 10-year government bond yields. Against the

backdrop of a moderate growth and inflation outlook as well as a

gradual normalisation of monetary policies, the DM GDP-weighted

government bond yield is projected to rise modestly over the next

few years, to 4.6% from 3.4% in 2010 (see chart 30). Greece (7%

p.a.), Portugal (6.5%) and Ireland (6.2%) will face the highest

government bond yields over the next ten years due to high default

risk premia. Japan (below 1.5% p.a.) and Germany (around 4% p.a.)

are expected to pay the lowest market interest rates on new

government debt issues, as a result of comparably low inflation and

their status of “safe havens” (see chart 28).

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20

5

Baseline

2000-09 average

Sources: DB Research, IMF

16

30

Our nominal interest rate projection for inflation-linked debt is determined by our

underlying projections for the base (i.e. “real”) interest rate component on inflationlinked debt as well as the inflation rate.

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

Nominal effective interest

rate to rise gradually

Nominal effective interest rates (% p.a.)

A government not only has outstanding debt but also continuously

issues new debt at different maturities (short/medium vs. long-term

debt), in different currencies (domestic vs. foreign debt) and/or at

different types of interest-rate contracts (fixed, floating vs. inflationlinked debt). Hence, there is no single market interest rate that

represents a sovereign‟s ultimate borrowing costs. While sovereign

bond yields reflect the current conditions at which governments are

able to borrow in financial markets, the financial costs of public debt

(i.e. the average nominal interest rate paid on total government debt

outstanding) is given by the nominal effective interest rate. As

explained in Box 1 on page 11, a country‟s current nominal effective

interest rate depends on a host of factors. In short, it depends on the

debt structure, the prevailing market interest rates (at which a

government is currently able to issue new debt), the inflation rate as

well as the nominal effective interest rate(s) of the previous year.

The lower the average maturity of outstanding government debt and

the higher the share of floating-rate and inflation-linked debt in total

debt, the more quickly the nominal effective interest rate adjusts

upwards to rising market interest rates or higher inflation.

Nominal interest rate, %

(DM PPP GDP-weighted average)

7

6

5

4

3

2

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20

Effective rate** (baseline)

Market rate* (baseline)

Effective rate** (2000-09 average)

Market rate* (2000-09 average)

* Gauged by 10-year government bond yields. ** Past

nominal effective interest rates on total public debt

outstanding were approximated by the ratio of annual

gross public debt interest payments to the previous

year's gross public debt stock.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global

Insight, Australian Bureau of Statistics

31

Nominal effective interest rate

%

8

6

4

2

0

JP

SE

CH

DE

FR

DK

US

ES

Avg. 2000-09**

BE

GB

SK

Avg. 2011-20

IT

CA

AU

PT

IE

GR

DM*

2010**

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average. **Past nominal effective interest rates on total public debt outstanding were approximated by the ratio of annual gross public debt interest

payments to the previous year's gross public debt stock.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global Insight, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Real interest rate to

converge to long-term avg.

Real effective interest rate, %

(DM PPP GDP-weighted average)

5

4

3

2

1

0

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20

Baseline

2000-09 average

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global

Insight, Australian Bureau of Statistics

33

We approximate the sample economies‟ past nominal effective

interest rates by the ratio of gross government debt interest

payments to the previous year‟s gross government debt stock. The

data employed for the calculation of nominal effective interest rates

comes from the OECD‟s Economic Outlook database and refers to

6

the general government level. Nominal effective interest rate

projections for 2011-20 depend on the initial effective interest rate

level and our market interest rate and inflation projections, as well

as a government‟s interest-cost sensivity to changing financial

market conditions. The DM GDP-weighted nominal effective interest

rate is projected to rise gradually to around 4.2% by 2020 owing to

higher market interest rates (see chart 31). While Greece, Ireland

and Portugal are projected to face the highest nominal effective

interest rates, at 6.1%, 5.5% and 5.4% per year over the outlook

period due to high default risk premia, respectively, Japan is

estimated to effectively pay only 1.4% p.a. on its outstanding gross

government debt stock thanks to subdued inflation and very low

government bond market yields (see chart 32).

6

July 6, 2011

32

The only exception is Australia where gross general government interest payments

(“interest expenses other than nominal superannuation”) come from the Australian

Bureau of Statistics.

17

Current Issues

Real effective interest rate

%

8

6

4

2

0

-2

JP

SE

SK

DE

FR

DK

GB

BE

US

Avg. 2000-09

IT

ES

AU

CH

CA

Avg. 2011-20

PT

IE

GR

DM*

2010

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global Insight, Australian Bureau of Statistics

34

Real effective interest rate (% p.a.)

In our March 2010 paper, we approximated real effective interest

rates by the prevailing CPI-deflated benchmark government bond

yield. We now gauge real effective interest rates by the CPI-deflated

nominal effective interest rates. These are the final outcome of (a)

7

the countries‟ underlying public debt structures and hence their

sensivities to changing market conditions, (b) the countries‟ initial

nominal effective interest rates approximated by the OECD‟s public

debt and fiscal data, and (c) our baseline scenario projections for

market interest rates and inflation. The DM GDP-weighted real

effective interest rate, which temporarily spiked to around 3.4% in

2009 because of slumping inflation rates, is projected to rise again,

though only moderately, to 2.3% p.a. by 2020, from 1.2% p.a. this

year (see chart 33 on page 17). Although the real effective interest

rate is seen to converge to its 2000-09 annual average of around

2.4%, it is still projected to remain far below levels observed during

the late 1990s. Going forward, a continuation of expansionary

monetary policies in major DMs as well as abundant global liquidity

may prevent a more pronounced increase in the DM average real

effective interest rate. At the country level, there are large

differences as regards to real effective interest rates (see chart 34).

While the 2011-20 average real effective interest rates are expected

to be highest in Greece (4.9% p.a.), Ireland (4.0% p.a.) and Portugal

(3.6% p.a.), they are projected to be lowest in Japan (0.7% p.a.).

Interest-rate/growth

differential to remain fairly

balanced

Interest-rate/growth differential, pp

(DM PPP GDP-weighted average)

8

6

4

2

0

-2

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20

Baseline

2000-09 average

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global

Insight, Australian Bureau of Statistics

35

Interest-rate/growth differential

Percentage points

8

6

4

2

0

-2

-4

SK

SE

JP

AU

US

GB

FR

DK

Avg. 2000-09

DE

BE

CA

Avg. 2011-20

ES

CH

IT

IE

PT

GR

DM*

2010

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global Insight, Australian Bureau of Statistics

7

18

36

As in Becker (2011), we make the simplifying assumption that a country‟s public

debt structure remains constant over the outlook period.

July 6, 2011

Public debt in 2020: Monitoring fiscal risks in developed markets

Interest-rate/growth differential (percentage points)

Consolidation at different

speeds in major DMs ...

Generally, the interest-rate/growth differential determines the

underlying trend of a country‟s public-debt-to-GDP ratio in the event

of a balanced primary account. The primary balance is the fiscal

balance before net debt interest payments. In case of a positive

differential (interest rates exceed growth) the public debt ratio will

trend upwards unless the government achieves sufficiently large

primary surpluses. Likewise, a negative differential (interest rates

are lower than economic growth) the debt ratio will remain on a

falling trend if the government does not run large primary deficits. As

a result of our real growth and effective interest rate assumptions,

the DM GDP-weighted interest-rate/growth differential is projected to

be fairly balanced in our baseline scenario (see chart 35). At the

country level, Greece, Portugal and Ireland are projected to face the

widest interest-rate/growth differentials of 3.3, 2.9 and 1.1 pp,

respectively, while Slovakia or Sweden, for instance, will benefit

from comparably large negative interest-rate/growth differentials

(see chart 36). On the one hand, Greece, Ireland and Portugal have

to run relatively large primary surpluses to keep public debt in check

because of unfavourable interest-rate/growth differentials. On the

other hand, Slovakia or Sweden could stabilise or lower current

public debt levels even when running mild primary deficits.

Primary balance, % of GDP

4

2

0

-2

-4

-6

-8

-10

06

08

10

12

14

16

FR

GB

JP

US

18

20

DE

37

Sources: DB Research, OECD

... but abrupt consolidation

in most EMU peripherals

Primary balance, % of GDP

10

0

-10

-20

Primary balance (% of GDP)

-30

06

08

10

12

ES

PT

14

16

18

GR

IT

The only economic variable that can be directly influenced by the

government, either via changes in the tax rate/base or adjustments

in public expenditures, is the primary balance. Historical primary

balance data is taken from the OECD‟s Economic Outlook database

(No. 89, May 2011) and refers to the general government level.

While most of the EMU peripheral countries are projected to

consolidate sharply over the forecast period due to persistent

financial market pressures (see chart 38), consolidation is expected

to take place at very different speeds in major DM economies. While

the UK has already launched a consolidation programme and is

seen to close its primary deficit by 2016, the US and Japan still lack

clear consolidation plans and are expected to adjust only gradually

over time (see chart 37). As a result, the DM GDP-weighted primary

deficit will narrow from 6.6% of GDP in 2010 to 1.5% by 2016 (see

chart 39). As population ageing will increasingly weigh on fiscal

accounts and make further improvements in the primary balance

harder to achieve, we assume that the DM primary balance will

continue to post a mild deficit of 1.5% of GDP for the remainder of

the outlook period.

20

IE

Sources: DB Research, OECD

38

Fiscal consolidation to

advance gradually

Primary balance, % of GDP

(DM PPP GDP-weighted average)

4

2

0

-2

-4

-6

-8

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20

Baseline

2000-09 average

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF, IHS Global

Insight

39

Primary balance

% of GDP

4

2

0

-2

-4

-6

2010:

- 30

-8

-10

JP

US

SK

GB

ES

IE

Avg. 2000-09

CA

FR

AU

BE

DE

Avg. 2011-20

PT

CH

DK

IT

SE

GR

DM*

2010

* DM PPP GDP-weighted average.

Sources: DB Research, OECD, IMF

July 6, 2011

40

19

Current Issues

Change in DM primary balances: 2020 vs. 2010 level