Vol. 33 No. 2

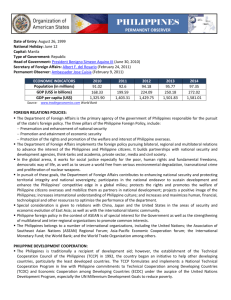

advertisement