Speech-Language Pathologists' Responses on Surveys on

Speech-Language Pathologists’

Responses on Surveys on Vocational

Stereotyping (Role Entrapment)

Regarding People Who Stutter

Eric Swartz

Rodney Gabel

Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH

Stephanie Hughes

Governors State University, University Park, IL

Farzan Irani

Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH

A ccording to several authors, (Bramlett, Bothe,

& Franic, 2006; Craig, Blumgart, & Tran,

1998; Manning, 2001; Yaruss & Quesal, 2004), stuttering

2009; Klompas & Ross, 2004; Linn & Caruso, affects personal relationships and the quality of life for

ABSTRACT: Purpose: The purpose of this research study was to explore whether speech-language pathologists (SLPs) exhibit vocational stereotyping (role entrapment) toward people who stutter (PWS). Also, the effects of certain educational and professional experiences on the reports made by SLPs were examined.

Method: The Vocational Advice Scale (VAS; R.M. Gabel, G.

Tellis, & M.T. Althouse, 2004), which is a scale with 43 careers, was completed by 158 SLPs. A demographic and open-ended questionnaire was also completed by the SLPs to identify factors that influenced their choices on the VAS.

Results: The results indicated the presence of role entrapment for only 2 of the careers on the VAS — attorney and speech pathologist—which were perceived to be less advisable or appropriate for males who stutter (MWS). This finding provides limited support for the notion that PWS suffer from role entrapment. Examination of the open-ended questions revealed that some SLPs would be supportive of

MWS in various types of careers, but others commented on people who stutter (PWS) because of the impact that stuttering has on verbal communication. In addition, stuttering causes PWS to experience undesirable behaviors, feelings, and thoughts caused by the anticipation of negative listener reactions to stuttering (Hulit & Wirtz, 1994; Yaruss & how stuttering would negatively affect the career choices of

MWS or made general comments about the careers.

Conclusion: Vocational stereotyping was found in only 2 out of 43 careers assessed in the study. Thus, it appears that stuttering did not lead to reports of role entrapment by this group of SLPs. Additionally, the total number of PWS whom the SLPs had treated in their career and the number of courses the SLPs had taken in stuttering had no effect on the participants’ responses. However, participants who had engaged in professional readings in stuttering were more likely to provide positive advice to MWS for 2 of the careers. Future research might consider using different research approaches, including qualitative and mixed methods approaches, when studying role entrapment by SLPs. These methods might allow for a deeper understanding of this phenomenon.

KEY WORDS: Vocational Advice Scale, stuttering, vocational stereotyping, role entrapment

C

ONTEMPORARY

I

SSUES IN

C

OMMUNICATION

S

CIENCE AND

D

ISORDERS

• Swartz et al.: Role Entrapment of PWS 157

1092-5171/09/3602-0157

Quesal, 2004). Silverman (1996) discussed the importance of listener reactions, which can affect how PWS cope with stuttering and may negatively impact their self-perception.

Because of the potential impact of both the speech of

PWS and the attitudes of others toward stuttering, speechlanguage therapy should consider both the individual who stutters and how he or she manages listeners. Some research has shown that reported attitudes of speech-language pathologists (SLPs) toward PWS are as negative as those of the general population (Cooper & Cooper, 1996; Cooper

& Rustin, 1985; Lass, Ruscello, Pannbacker, Schmitt, &

Everly-Myers, 1989; Ragsdale & Ashby, 1982; White &

Collins, 1984), and that SLPs are undertrained to work with

PWS (Brisk, Healey, & Hux, 1997). For this reason, it is important to consider the possibility that negative attitudes of some SLPs lead to stereotyping of PWS.

Allport (1986, p. 191), defined stereotyping as “an exaggerated belief associated with a category. The function of stereotypes is to justify (rationalize) our conduct in relation to that category.” Stereotypes can be harmful because they create beliefs about people with disabilities by disregarding their individuality. Smart (2001) suggested that stereotyping is negative for several reasons. First, when people are stereotyped, they are no longer portrayed as individuals.

Second, stereotypes isolate and separate individuals from the general population. Finally, all stereotypes foster actions and beliefs that inhibit and reduce the opportunities of the group of people who are stereotyped (Smart, 2001).

Several research studies have found that a negative stereotype of PWS exists in the general population (e.g.,

Dorsey & Guenther, 2000; Kalinowski, Armson, Stuart, &

Lerman, 1993; Woods & Williams, 1976). Research has been conducted that examines how people who do not stutter (PWDS) form stereotypes. White and Collins (1984) reported that the stuttering stereotype is created as PWDS infer what it feels like to stutter. As a result of stressful or anxiety-provoking situations that cause them to experience temporary disfluency, PWDS may develop negative attitudes and stereotypes related to stuttering and PWS (White

& Collins, 1984).

There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that

SLPs stereotype PWS. Yairi and Williams (1970) examined SLPs’ stereotypes of elementary-age boys who stutter. In their study, 127 SLPs listed adjectives (traits) that described boys who stutter. The most common traits were nervous, shy, withdrawn, tense, anxious, and selfconscious . The average number of traits provided increased with an SLP’s years of experience, suggesting that years of experience actually strengthened the SLPs’ stereotypes.

In a similar study, Woods and Williams (1971) examined

SLPs’ perceptions of males who stutter (MWS). The results of this study were similar to the results found by Yairi and Williams. In another study, Turnbaugh, Guitar, and

Hoffman (1979) also found that SLPs considered PWS, regardless of stuttering severity, to be more self-conscious, hesitant, fearful, anxious, insecure, afraid, sensitive, intelligent, nervous, and tense than PWDS. Another finding was that years of experience as an SLP did not alter one’s tendency to stereotype PWS. Thus, when considering these findings, it appears that SLPs maintain a persistent, unwavering negative stereotype of PWS despite their years of experience as a clinician.

Similar research by Cooper and Rustin (1985) found that a significant number of SLPs in the United States and

Great Britain thought that PWS exhibited distorted perceptions of social relationships, possessed feelings of inferiority, or held characteristic personality traits. A follow-up study was conducted by Cooper and Cooper (1996), and the results were compared to those of an earlier study (Cooper & Cooper, 1985). Though some positive changes were noted, SLPs continued to report negative and stereotypical attitudes toward PWS, suggesting that SLPs’ attitudes toward PWS have remained largely unchanged for several decades.

More recently, Brisk et al. (1997) examined SLPs’ perceptions and attitudes toward PWS. Specifically, they measured

SLPs’ attitudes toward working with children who stutter by administering a survey to 500 SLPs who worked in schools across the United States. The survey contained 28 Likertscale questions and 11 checklist items. The results indicated that SLPs continue to have negative perceptions about children who stutter, as 43% of the SLPs reported that children who stutter are shy and withdrawn. Half of the SLPs who were surveyed believed that children who stutter exhibit excessive tension and stress. Although these SLPs had negative perceptions about children who stutter, the majority of participants believed that their clinical intervention had a positive impact on children who stutter.

One negative consequence of stereotyping is role entrapment (vocational stereotyping). Role entrapment occurs when people in the majority population, such as PWDS, define and limit the roles of people in the minority population, in this case, PWS (Smart, 2001). Role entrapment is either social or occupational in nature (Smart, 2001). Social role entrapment occurs when people with disabilities are covertly or overtly excluded from social activities because they are perceived as being different. An extreme case of social role entrapment would be segregation (Smart, 2001).

Occupational role entrapment occurs when a person with a disability is relegated to a job based solely on a singular characteristic, such as a disability.

There is limited research as to whether PWS experience role entrapment. Gabel et al. (2004) conducted a study that used the Vocational Advice Scale (VAS; Gabel et al., 2004) to determine if occupational role entrapment exists for

PWS. The VAS includes 43 items in which participants are directed to indicate their perceptions of appropriate careers for PWS. Gabel et al. administered the VAS to 385 university students and found that participants reported that 20 of the careers were less appropriate for PWS as compared to

PWDS. These findings support the hypothesis that occupational role entrapment does exist for PWS. In addition, the authors suggested that university students believed that professions requiring a higher amount of communication ability were not appropriate for PWS. Conversely, those careers requiring less communication were perceived by study participants as being more suitable for PWS. These findings suggest that occupational role entrapment for PWS exists, and that PWS may experience difficulty when pursuing careers requiring high levels of verbal communication.

158 C

ONTEMPORARY

I

SSUES IN

C

OMMUNICATION

S

CIENCE AND

D

ISORDERS

• Volume 36 • 157–165 • Fall 2009

Gabel, Hughes, and Daniels (2008) also explored whether university students project perceptions of role entrapment onto PWS. Specifically, this study examined whether stuttering severity and amount of therapy involvement (i.e., choosing to participate or not participate in speech therapy) affected university students’ perceptions of appropriate careers for PWS. The university students involved in this study completed the VAS (Gabel et al., 2004) for a hypothetical adult male who stutters in four different situations:

(a) a male who stutters mildly who is in speech therapy, (b) a male who stutters severely who is in speech therapy, (c) a male who stutters severely who is not in speech therapy, and (d) a male who stutters mildly who is not in speech therapy. The results indicated that stuttering severity and the decision to participate or not participate in speech therapy did not lead to role entrapment; however, many university students reported that PWS would be well suited to careers in technology and science, which may have been perceived as requiring less communication than other careers.

In another study, Irani, Gabel, Hughes, Swartz, and

Palasik (in press) explored whether K–12 schoolteachers reported role entrapment of PWS and whether variables related to exposure to stuttering would influence their reports.

This study also used the VAS to study role entrapment. A total of 204 teachers identified 10 careers as less advisable for PWS. These careers appeared to be those that required more communication ability, similar to the study by Gabel et al. (2004). In addition, the study found that variables related to exposure to stuttering did not impact the teachers’ responses on the VAS. In total, the findings of this study did not support that teachers are prone to have attitudes toward PWS that are indicative of role entrapment.

To date, few studies have explored whether PWS experience role entrapment. Studies completed on this topic have explored the attitudes that university students and schoolteachers have toward role entrapment of PWS (Gabel et al.,

2004; Gabel et al., 2008; Irani et al., in press; Lass et al.,

1992). It is important to note that other studies suggest that stuttering is also perceived to affect employment and how individuals are viewed in certain careers (Hurst & Cooper,

1983a, 1983b; Silverman & Bongey, 1997). Though university students represent a general population of individuals who might impact the career decisions of PWS, the presence of reported role entrapment made by other groups of individuals is also important. Specifically, it would appear necessary to explore whether SLPs will report role entrapment of PWS. SLPs might play a role in counseling and advising PWS related to many life decisions, including career choice. Because previous studies have found that SLPs report negative stereotypes of PWS (Brisk et al., 1997;

Cooper & Cooper, 1996; Cooper & Rustin 1985; Turnbaugh et al., 1979; Woods & Williams, 1971; Yairi & Williams,

1970), it is vitally important to identify whether SLPs will report role entrapment of PWS.

Before this research study, role entrapment of PWS by

SLPs has not been investigated. The following questions will guide this research:

• Will SLPs advise PWS to pursue fewer careers than

PWDS?

• Do the following factors influence the judgments made by SLPs related to appropriate career choices for PWS?

– Having individuals who stutter on one’s caseload

– Completing more course work in stuttering

– Completing professional readings in stuttering

METHOD

Participants

One hundred and fifty-eight SLPs , 13 males (8.2%) and

145 females (91.8%), completed the VAS to determine the attitudes of SLPs toward PWS. The SLPs had an average of 15.8 years of experience. The SLPs also completed a demographic and an open-ended questionnaire to identify factors that influenced their choices. The average age of the participants was 42 1 /

2

years, with an age range of 25–75 years. Two respondents not included in the 158 SLPs selfidentified as PWS and so were excluded from the study.

Demographic data for the participants were gathered using a one-page questionnaire. A large percentage of participants (83.9%) reported knowing someone who stutters, most typically as a client (30.2%) or a friend (25.3%). The vast majority of participants (98.1%) held the Certificate of Clinical Competence (CCC) from the American Speech-

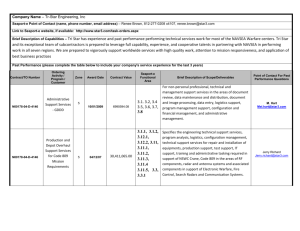

Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Ninety-five percent of the respondents held a master’s degree; in addition, 1.6% indicated that they were fluency specialists, and 11.1% reported that they belonged to a professional organization related to stuttering. Although the majority of participants had taken at least one course related to stuttering, 3.8% had never taken a stuttering course. Years of professional experience as an SLP ranged from 1.4 to 41.0 years, with an average of 15.9 years. Participants’ case-loads ranged from 0 to 100 clients, with an average of 31.4 clients. Only a small percentage of participants (3.1%) reported never having a client who stutters on their caseload. On average, participants had 3.5 clients who stutter on their caseload and had treated an average of 9.8 PWS over the course of their career. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Survey Instrument

Study participants were also required to complete the VAS.

The VAS was developed to measure people’s perceptions of appropriate career choices for PWS, focusing on role entrapment. The VAS asks respondents to estimate, using a 5-point Likert-type scale in which 5 indicates strongly agree and 1 indicates strongly disagree, whether they would advise a person, if he or she was qualified, to train for one of 43 careers. When interpreting the VAS, a specific career is judged as less advisable for PWS if the participants assign them a lower score on a particular item as compared to PWDS. According to Gabel et al. (2004), the VAS has acceptable psychometric properties. An open-ended question, “If you did not agree or strongly agree with one or more of the items, or did not agree that you would advise

Swartz et al.: Role Entrapment of PWS 159

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic information.

Demographic item

Age of participants

Gender

Ethnicity

Do you know someone who stutters?

Who is this person?

Number of years as an SLP

Number of years in your present position

Size of your present caseload

Do you have any PWS on your present caseload?

Number of PWS you worked with during your career

Number of courses you have taken in stuttering

Highest degree obtained

Do you hold the CCC?

Do you belong to any professional organizations

related to stuttering?

Are you a fluency specialist?

Have you ever done any professional reading about

stuttering?

Number of people who filled out the condition 1 or

condintion 2 questionnaire

M = 42.42; SD = 10.81

Female = 145 Male = 13

Caucasian = 148

NA = 4

African American = 4

Asian = 1

Latino = 1

Yes = 133 No = 25

Client = 49

Friend = 40

No one = 24

Other relative = 14

Other professional = 12

Student = 6

Colleague = 6

Neighbor = 3

Parents = 1

M = 15.81; SD = 10.21

M = 10.48; SD = 16.40

M = 31.37; SD = 23.41

Yes = 78 No = 80

0–5 = 64

6–10 = 54

11–20 = 29

> 20 = 6

0–1 = 77

2 or more = 81

MA/MS = 152

PhD/Doctorate = 6

Yes = 155 No = 3

Yes = 18 No = 140

Yes = 2 No = 156

Yes = 129 No = 29

Condition 1 = 98

Condition 2 = 60

Note.

PWS = people who stutter; CCC = Certificate of Clinical Competence; condition 1 = PWS; condition

2 = people who do not stutter.

this person to pursue one or more of these careers, please explain why,” followed the Likert-type scale.

In this study, each participant received one of two possible sets of instructions on the VAS . One set of instructions directed participants to “assume that this individual is a male, he is a person who stutters, and he has no other communication disorder.” The alternative set of instructions directed participants to “assume that this individual is a male, he is a person who does not stutter, and he has no communication disorder.” The instructions were limited to males because there is a 3 to 1 ratio of males to females who stutter (Bloodstein, 1995). Ninety-eight participants completed the survey for a male who stutters; 60 participants completed the survey for a male who does not stutter. A description of each career accompanied both versions of the survey because some participants may not have been familiar with the particular career and its associated responsibilities. The participants who completed the VAS for the male who stutters condition responded to an open-ended question at the end of the survey. This question allowed participants to share their reasoning for their responses to the VAS .

Procedure

SLPs listed in the ASHA membership directory were identified via randomized stratified sampling procedures.

160 C

ONTEMPORARY

I

SSUES IN

C

OMMUNICATION

S

CIENCE AND

D

ISORDERS

• Volume 36 • 157–165 • Fall 2009

Survey packets were mailed to the addresses that were obtained from the ASHA member directory and included both the survey and a return envelope with prepaid postage. In order to obtain a diverse sample of 600 SLPs, equal numbers of SLPs working in rural and urban settings in each of the 50 United States were selected. The 600

SLPs were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In the first condition, participants were asked to respond to the description of a male who stutters who had no other communication disorder. In the second condition, participants were asked to respond to the description of a male who does not stutter who had no communication disorder.

Participants responded to either condition using the VAS .

A total of 158 usable surveys were returned by participants

(26.3% response rate). Ninety-eight participants (62.0% of the final sample) returned the survey representing the male who stutters, and 60 participants (38.0% of the final sample) returned the survey representing the male who does not stutter. The relatively low overall response rate may be attributable to the time of the year when the surveys were mailed to participants (i.e., May/June is often a busy time for SLPs in the school system). Furthermore, some members in the ASHA membership directory may have changed their mailing address without updating their contact information.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis. Descriptive statistics and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistic were performed on the data set. The data from participants’ responses to the

VAS and accompanying demographic questions were analyzed using SPSS-15 software. Descriptive statistics (mean score and standard deviation) were completed for each of the 43 careers and the total mean score on the VAS. The data were arranged so that comparisons could be made between responses to the two conditions (male who stutters and male who does not stutter) for subgroups of participants (e.g., years of experience as an SLP, course work in stuttering versus no course work, etc.) and for responses to the overall score on the VAS and the 43 individual items.

These data were then analyzed to provide the mean scores for both the male who stutters and the male who does not stutter condition. Careers with lower mean scores indicated that a particular career was a less appropriate career choice than a career with a higher mean score.

ANOVA. Reports for each of the 43 careers and the overall mean score were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA.

The ANOVA was used to compare whether certain careers were more or less advisable for MWS compared to MWDS.

A career was identified as less advisable if its p value was

.001 or less. The ANOVA also indicated if stuttering was perceived to have an overall effect on occupational choices

(the overall mean score) for MWS versus MWDS. A more conservative alpha level of .001 was used because there were 44 ANOVAs in this study divided by the alpha level

(.05). This adjustment accounted for the variability that accompanies a large number of comparisons.

For the 98 participants who responded to the males who stutter condition, three separate ANOVAs were conducted to ascertain whether any of the following conditions had an effect on the reports made by the respondents for each of the 43 items and the overall mean score on the VAS: (a) having individuals who stutter on the present caseload, (b) engaging in professional readings about stuttering, or (c) completing a stuttering course. Two of the ANOVAs consisted of variables that were yes/no questions (e.g., PWS on caseload and engaging in professional readings). The third

ANOVA, related to the number of stuttering courses taken, consisted of those individuals who took two or more stuttering courses and those who had taken one or no stuttering courses. The three ANOVAs were completed to explore whether these variables affected responses to each item and the overall mean score on the VAS.

Qualitative analysis. Responses to the open-ended question were compiled and analyzed for important themes. The open-ended question was, “If you did not agree or strongly agree with one or more of the items, or did not agree that you would advise this person to pursue one or more of these careers, please explain why.” To establish credibility and reliability of the responses, 30% of the statements were independently coded by three of the authors. The first author initially analyzed the data, then two of the co- authors independently analyzed 30% of the statements for relevant themes. In addition, the first author recoded 30% of the statements 2 weeks after they were first analyzed. A

Pearson’s product–moment correlation was used to correlate the two sets of coded responses, and the responses were compared using a t test to examine both inter- and intrajudge reliability.

Interjudge reliability of the assigned codes showed a positive correlation, significant at a 0.05 alpha level for judges one and two ( r = .86; p ≤ .01), and judges one and three ( r

= .86; p ≤ = .01). The t test results indicated no significant differences between judges one and two ( t = –.38; p = .71) and judges one and three ( t = –.31; p = .71). These data suggest good interjudge reliability for these codes. Intrajudge reliability was completed by the first author completing the analysis of the data on two occasions, with the first analysis taking place 2 weeks before the second analysis.

Results of intrajudge reliability indicate a positive correlation ( r = 1.00; p = .01) and no significant differences ( t =

.00; p = 1.00) between the analysis, thereby establishing satisfactory intrajudge reliability.

RESULTS

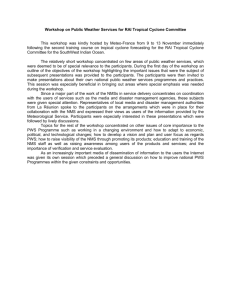

Table 2 is arranged in ascending order according to responses for the male who stutters condition; that is, the career receiving the lowest mean score appears first, and the career receiving the highest mean score appears last.

For MWS, attorney had the lowest mean score (3.40, SD

= 1.10), and computer programmer and biologist had the highest mean score (4.18, SD = 0.74; 4.18, SD = 0.78).

Hence, computer programmer was judged as the most appropriate career for a hypothetical adult male who stutters. In contrast, attorney was viewed as the least appropriate career for a hypothetical adult male who stutters.

Swartz et al.: Role Entrapment of PWS 161

Table 2.

Comparison of mean values of participants’ responses for career advice to a hypothetical male who stutters ( n = 98) and a hypothetical male who does not stutter ( n = 60)

Career

Male who stutters

Mean SD

Male who does not stutter

Mean F value

Attorney

Judge

Psychologist

Speech-language 3.78 0.93

Physician 3.78 0.95

Meteorologist

Astrologer

3.81 1.01

3.83 0.94

3.86 1.05

3.87 0.93

Optometrist

Chiropractor

Optician

Pharmacist

3.89 0.86

3.91 0.89

3.91 0.89

3.93 0.83

3.94 0.85

3.95 0.87

3.95 0.84

3.97 0.83

Urban/regional planner

Sociologist

Physiologist

Historian

Audiologist

Medical records technician

Medical laboratory technician

Computer service technician

Accountant

4.97

4.01

0.83

3.98 0.84

4.00 0.78

0.86

4.04 0.80

4.05 0.82

4.07 0.80

4.07 0.79

4.08

4.09

0.80

0.83

4.10 0.78

4.10 0.78

Motion picture editor

Statistician

3.40 1.10

3.50 1.10

3.52 1.07

3.52 0.99

3.68 1.03

3.70 0.98

Mathematician

Computer systems analyst

Engineer

Biologist

Computer programmer

Total

4.11 0.78

4.12 0.76

4.12 0.75

4.13 0.75

4.14 0.77

4.16 0.74

4.17 0.76

4.18 0.78

4.18 0.74

3.94 0.73 p value

4.05 0.95 14.491 0.000*

4.02 0.89 9.480 0.002

3.87 1.05 3.969 0.048

3.97 0.86 8.244 0.005

4.05 0.87 5.262 0.023

4.00 0.96 3.472 0.064

4.10 0.77 6.675 0.011

4.27 0.80 11.594 0.001*

4.13 0.79 5.995 0.015

4.15 0.82 4.940 0.028

3.98 0.93 1.042 0.309

3.88 1.03 0.024 0.878

3.97 0.96 0.417 0.519

3.92 0.98 0.038 0.846

4.12 0.83 2.169 0.143

4.12 0.83 2.169 0.143

3.92 0.96 0.007 0.934

4.25 0.77 5.362 0.022

4.05 0.91 0.487 0.486

4.18 0.87 2.804 0.096

4.07 0.80 0.525 0.470

4.12 0.74 1.271 0.261

3.93 0.94 0.104 0.748

4.20 0.75 2.481 0.117

3.98 0.98 0.033 0.857

4.27 0.76 3.099 0.080

3.92 0.94 0.893 0.346

4.02 0.89 0.159 0.691

4.17 0.81 0.533 0.467

4.17

4.12

0.81

0.90

0.421

0.031

0.517

0.860

4.15 0.80 0.138 0.711

4.17 0.85 0.239 0.625

4.13 0.81 0.026 0.872

4.03 0.90 0.441 0.507

4.08 0.85 0.091 0.763

4.13 0.83 0.000 0.996

4.02 0.91 0.864 0.354

4.17 0.76 0.001 0.978

4.28 0.72 0.813 0.369

4.20 0.78 0.016 0.898

4.12 0.92 0.253 0.615

4.08 0.74 1.451 0.230

*Significant at p ≤ .001.

Between-Group Comparisons

ANOVA.

An ANOVA for the overall score on the VAS was completed to determine the combined effect that stuttering had on the respondents’ perceptions of appropriate career choices for MWS. A lower total mean score indicated that the respondent perceived the career to be a less appropriate choice for the hypothetical male who stutters than the hypothetical male who does not stutter. The mean score for the male who stutters condition was 3.94 ( SD = .73); the mean score for the male who does not stutter condition was 4.08 ( SD = .74). There was no significant difference between these scores ( p > .05), suggesting that both groups reported relatively positive attitudes toward all of the careers for the hypothetical individual they evaluated

(i.e., male who stutters or male who does not stutter). An

ANOVA was conducted for each of the 43 careers on the

VAS to explore which careers were considered to be more or less appropriate for PWS. Table 2 displays the results.

Attorney and SLP were the only two careers that were significant ( p < .001). Moreover, these two careers were perceived to be less advisable for a hypothetical male who stutters.

Within-Group Comparisons

An analysis of the responses of the 98 participants in the male who stutters condition was completed to determine

162 C

ONTEMPORARY

I

SSUES IN

C

OMMUNICATION

S

CIENCE AND

D

ISORDERS

• Volume 36 • 157–165 • Fall 2009

how certain variables affected the participants’ perceptions of appropriate career choices for PWS. Three different ANOVAs were performed for each of the 43 careers and the overall mean score to assess the effect of (a) the total number of PWS the participants had treated in their career as an SLP, (b) the number of courses they had taken in stuttering, and (c) whether participants had engaged in professional readings in stuttering. The results indicated that there were no significant differences ( p > .001) for the variables of total number of PWS treated and number of courses taken in stuttering. However, SLPs who reported completing professional readings in stuttering were more likely to advise a male who stutters to become a judge ( F

= 11.20; p < .001), hospital administrator ( F = 11.47; p

< .001), guidance/employment counselor ( F = 14.08; p <

.000), attorney ( F = 14.93; p = .000), and physician ( F =

9.94; p = .001). This finding suggests a positive impact of professional reading on reports for these five careers.

Open-Ended Question

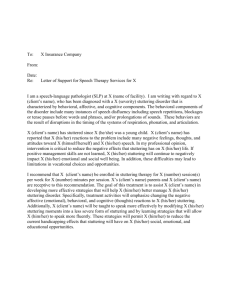

Participants were asked to answer one open-ended question at the end of the survey instrument: “If you did not agree or strongly agree with one or more of these items, or did not agree that you would advise this person to pursue one or more of these careers, please explain why.” Twenty-four participants assigned to the male who stutters condition provided a written response to the open ended question.

The qualitative data from the 24 participants were coded into one of three themes using thematic analysis. The theme related to profession was used when the response included characteristics of a particular profession, or the respondent’s attitudes toward the career guided his responses; for example, “psychologist seems like a rewarding job.”

The theme related to stuttering was used when participants felt that PWS should not do a particular job because of their stuttering; for example, “A computer programmer would be a good job for a PWS since they would not have to talk much.” The theme supportive was used when participants provided statements that were supportive of PWS; for example, “I think a PWS should go for any career they want.” The highest number of comments were represented in the related to stuttering ( n = 10) and supportive ( n =

9) categories; fewer ( n = 5) were in the related to career category. These themes are summarized in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

In general, SLPs did not report vocational stereotypes or vocational role entrapment for PWS. That is, only the professions of attorney and speech therapist were reported to be less advisable for a male who stutters than for a male who does not stutter. Furthermore, participants did not disagree or strongly disagree that a particular career was less suitable for a male who stutters versus a male who does not stutter. Additionally, there was not a significant difference reported for participants’ overall mean scores for the male who stutters and the male who does not stutter condition.

The careers attorney and speech therapist were reported as being less advisable for a male who stutters than a male who does not stutter on this study and several other studies (Irani et al., in press; Gabel et al., 2008; Gabel et al.,

2004). One can speculate that these two careers were perceived as being less advisable for MWS because they require proficient verbal communication skills. In addition to the use of SLPs for stereotyping research, there have been other participants used to measure stereotyping of PWS with the VAS. Gabel et al. (2004), who recruited university students, found 20 careers less advisable for MWS than for MWDS. Irani et al. (in press), who recruited teachers, found 10 careers less advisable for MWS than for MWDS.

The findings from the current study suggest that having clients who stutter on one’s caseload and completing courses in stuttering did not have an impact on role entrapment of PWS. There are at least two potential reasons for this particular finding. First, the SLPs in this study may have already held positive attitudes toward career choices for

PWS before working with PWS or taking additional course work on stuttering. A more likely reason for this finding is that the SLPs in this study were predisposed to provide

Code

Related to profession

Related to stuttering

Supportive

Table 3.

Thematic analysis of participants’ responses to the open-ended question.

“An astrologer seems like a poor profession for anyone to become. There is much more in life than believing in astrology.”

“The occupation of judge and hospital administration involves a lot of conversing with very influential people, and unless the person has learned very good strategies/use of equipment to prevent any occurrences of nonfluencies, it would be very uncomfortable for them professionally and for those involved.”

“I would encourage anyone to pursue what their interest is regardless of gender or communication issues.

I would recommend to work towards your passion and make it happen.”

Number of Percentage of responses responses

5 21

9

10

38

42

Swartz et al.: Role Entrapment of PWS 163

positive reports of career advice for PWS; thus, working with PWS or taking additional course work were not likely to alter an already positive predisposition in this group toward appropriate career choices for PWS. Exploring these hypotheses in a larger population of SLPs or engaging in alternative research methods, such as an experimental design, will be important when exploring the effects of these variables in the future.

Completing professional readings related to stuttering was associated with positive career advice for five of the careers. Thus, continuing education activities may reduce role entrapment or educate SLPs regarding the abilities of

PWS. Also, it may be that those SLPs who are more likely to advise PWS to pursue these five careers are also those

SLPs who are more interested in stuttering, and who are subsequently more likely to pursue readings on this topic.

Twenty-four participants who were assigned to the MWS condition presented rationales for their judgments regarding the suitability of careers for PWS. Three themes arose from these statements: related to the profession, related to stuttering, and supportive. The majority of responses showed that SLPs believed that stuttering would affect the ability of a person who stutters to perform a career or reflected support for PWS when making career choices. For example, one participant wrote that PWS would not be able to be a judge or hospital administrator unless they were able to use strategies or devices to prevent “any occurrences of nonfluencies.” Such statements indicate that some SLPs believe that there is less tolerance (role entrapment) in some professions for stuttering. The supportive comments reflected the belief that PWS should pursue any career they want, even though they stutter. For example, one participant wrote, “I would encourage anyone to pursue what their interest is, regardless of gender or communication issues.”

Participants who provided supportive statements had the most positive outlook for PWS. The related to the profession statements were directed toward the attractiveness of the actual profession. For example, one participant stated that he did not like astrology: “There is so much more to life than believing in astrology.” Though these findings appear to suggest that some individuals were using stuttering as a factor in their judgments, it is also important to consider that a relatively small number of participants completed the open-ended report.

Limitations

A primary weakness of this study was the low survey response rate. Out of 600 surveys mailed, fewer than 30% were returned and fully completed. Hence, it is possible that the sample may not be descriptive of the general population of SLPs. Thus, the lower than expected return rate may limit the ability to generalize from these results.

Future studies regarding the attitudes of SLPs toward PWS should attempt to target designs that increase the return rate and sample size of the study, thereby allowing for generalization of the findings. Also, this study had a low number of qualitative responses in which participants provided their reasons for advising for or against certain careers. The 24 responses helped to explain the results from the VAS, but more responses to the open-ended question would have been useful. The authors were also unable to engage in member checking to ensure that the participants’ responses to the survey questions accurately represented their beliefs about appropriate careers for PWS. Member checking is conducted by asking research participants if the researchers’ conclusions accurately represent the sentiments of the individual participants (Maxwell, 1996). Without member checking, it was difficult to determine the participants’ reasoning for their responses. It was also difficult to determine whether the researchers’ inferences about the participants’ responses accurately represent the views of the SLPs in this study. Interviews with SLPs may have been helpful to more fully understand the participants’ responses. Future studies might consider taking a qualitative or mixed methods approach to studying this phenomenon, thereby allowing for a deeper understanding of the prevalence of role entrapment by SLPs.

REFERENCES

Allport, G. W.

(1986). The nature of prejudice (25 th anniversary ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bloodstein, O.

(1995). A handbook on stuttering (5th ed.). San

Diego, CA: Singular.

Bramlett, R. E., Bothe, A. E., & Franic, D. M. (2006). Preference-based measures to assess quality of life in stuttering.

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 381–394.

Brisk, D. J., Healey, E. C., & Hux, K. A.

(1997). Clinicians’ training and confidence associated with treating school-age children who stutter: A national survey. Language, Speech, and

Hearing Services in Schools, 28 , 164–176.

Cooper, E. B., & Cooper, C. S.

(1985). Clinician attitudes towards stuttering: A decade of change (1973–1983). Journal of

Fluency Disorders , 10 , 19–23.

Cooper, E. B., & Cooper, C. S.

(1996). Clinician attitudes towards stuttering: Two decades of change. Journal of Fluency

Disorders , 21 , 119–135.

Cooper, E. B., & Rustin L.

(1985). Clinician attitudes toward stuttering in the United States and Great Britain: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 10 , 1–17.

Craig, A., Blumgart, E., & Tran, Y.

(2009). The impact of stuttering on the quality of life in adults who stutter. Journal of

Fluency Disorders, 2, 61–71.

Dorsey, M., & Guenther, R. K.

(2000). Attitudes of professors and students toward college students who stutter.

Journal of Fluency Disorders, 25 (1), 77–83.

Gabel, R. M., Hughes, S., & Daniels, D.

(2008). Effects of stuttering severity and therapy involvement on role entrapment of people who stutter. Journal of Communication Disorders , 41,

146–158.

Gabel, R. M., Tellis, G., & Althouse, M. T.

(2004). Measuring role entrapment of people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 29 , 27–49.

Hulit, L. M., & Wirtz, L.

(1994). The association of attitudes towards stuttering with selected variables. Journal of Fluency

Disorders , 19, 247–267.

Hurst, M. I., & Cooper, E. B.

(1983a). Employer attitudes toward stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 8, 1–12.

164 C

ONTEMPORARY

I

SSUES IN

C

OMMUNICATION

S

CIENCE AND

D

ISORDERS

• Volume 36 • 157–165 • Fall 2009

Hurst, M. I., & Cooper, E. B. (1983b). Vocational rehabilitation counselors’ attitudes toward stuttering. Journal of Fluency

Disorders, 8, 13–27.

Irani, F., Gabel, R., Hughes, S., Swartz, E., & Palasik, S.

(2009). Role entrapment of people who stutter reported by K–12 teachers, Contemporary Issues in Communication Sciences and

Disorders, 36, 45–54.

Kalinowski, J., Armson, J., Stuart, A., & Lerman, J. W.

(1993).

Speech clinicians’ and the general public’s perceptions of self and stutterers. Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 17, 79–85.

Klompas, M. & Ross, E. (2004). Life experiences of people who stutter, and the perceived impact of stuttering on quality of life: personal accounts of South African individuals. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 29, 275–305.

Lass, N. J., Ruscello, D. M., Pannbacker, M. D., Schmitt, J. F.,

& Everly-Myers, D. S. (1989). Speech-language pathologists’ perceptions of child and adult female and male stutterers. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 14 , 127–134.

Lass, N. J., Ruscello, D. M., Schmitt, J. F., Pannbacker, M. D.,

Orlando, M. B., Dean, K. A., et al.

(1992). Teachers’ perceptions of stutterers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in

Schools, 23, 78–81.

Linn, G. W. & Caruso, A. J.

(1998). Perspectives on the effects of stuttering on the formation and maintenance of intimate relationships. Journal of Rehabilitation, 64, 12–15.

Manning, W.

(2001). Clinical decision making in fluency disorders. San Diego, CA: Singular.

Maxwell, J. A.

(1996). Qualitative research design . Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ragsdale, J. D., & Ashby, J. K.

(1982). Speech-language pathologists’ connotations of stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing

Research , 25 , 75–80.

Silverman, F., & Bongey, T.

(1997). Nurses’ attitudes toward physicians who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 22, 61–62.

Silverman, F. H.

(1996). Stuttering and other fluency disorders:

An overview for beginning clinicians.

Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Smart, J.

(2001). Disability, society, and the individual . Austin,

TX: Pro-Ed.

Turnbaugh, K., Guitar, B., & Hoffman, P.

(1979). Speech clinicians’ attribution of personality traits as a function of stuttering severity. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 26, 17–42.

White, P. A., & Collins, S. R. C.

(1984). Stereotype formation by inference: A possible explanation for the “stutterer” stereotype.

Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 27 , 567–570.

Woods, C. L., & Williams, D. E.

(1971). Speech clinicians’ conceptions of boys and men who stutter. Journal of Speech and

Hearing Disorders , 36 , 225–234.

Woods, C. L., & Williams, D. E.

(1976). Traits attributed to stuttering and normally fluent males. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research , 19 , 267–278.

Yairi, E., & Williams, D. E.

(1970). Speech clinicians’ stereotypes of elementary-school boys who stutter. Journal of Communication Disorders, 3, 161–170.

Yaruss, J. S., & Quesal, R. W.

(2004). Stuttering and the internal classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF): An update. Journal of Communication Disorders, 37 , 35–52.

Contact author: Eric Swartz, Department of Communication

Disorders, Bowling Green State University, 200 Health Center,

Bowling Green, OH 43403. E-mail: eswartz@bgsu.edu.

Swartz et al.: Role Entrapment of PWS 165