Consumer science beyond testing - Science Teachers' Association

advertisement

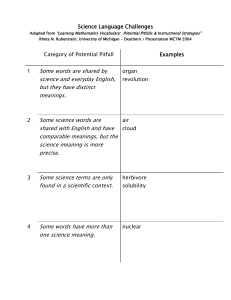

Consumer science beyond testing: Talking multiple meanings Cheryl Jakab, Jakab Creative All consumer decisions result to some extent in wider social, financial and environmental consequences. Each lifestyle choice, from which soap we decide to buy to unwanted packaging and brand loyalty, impacts on the environment, other people and businesses, as well as having personal efficacy and impacts on finances. Consumer literacy enables people to apply knowledge, skills and values to assess the impacts of consumer-related decisions on themselves, the community and the environment, now and in the future (Curriculum Corporation, 2008). In our 21st century consumer society, each person needs to develop critical skills to be able to assess the accuracy and appropriateness of available information and advertising claims within a wider context. In this process individual preferences and aesthetics often heavily influence choices, rather than rational analysis of claims and well thought through decisions. Having a positive attitude into ‘looking below the surface’ of the information and terminology presented by advertising, can result in major changes in personal choice and aesthetics, including what we choose to think about and what we value as important when making choices. Making informed choices Today general advertising, the media and lobby groups often use scientific sounding terminology and quote scientific testing to help sway consumer choice. Literacy in science, as a method of working (scientific thinking and reasoning and processes) and scientific knowledge (concepts, theories and principles), can help inform this personal decision-making. Appreciation of the relationships between science terms used in science classrooms, and science terms used as popularly understood symbols in everyday consumer society, by talking multiple meanings, can enhance school learning. 10 Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 Consumer science can help us determine all aspects of costs of our preferences, not just efficacy of products and determining value for money as compared to low price. Thus empowering learners with scientific consumer literacy by integrating it into science classroom practices can have a dual impact. It can assist students make informed choices as consumers and at the same time help make science classroom learning more meaningful, relevant and available to learners. The best potato chip product test Take for example the simple and very popular potato chip. How would you choose ‘the best chip’? (See Jakab and Keystone, 1997.) What tests would you do? How objective an assessment can this be? The fact that science as a process is much more messy than our usual science lessons suggest come out loud and clear in this type of study. This should not be considered a problem, but rather an asset to be utilized in helping students understand that science investigation is messy and not always a direct process using ‘the scientific method.’ Reacting to advertisements ‘Anything that is co-optable is going to be coopted by power systems for doctrinal purposes.’ Noam Chomsky linguist, New Scientist, 26th July 2008. As a way of preparing to read this article, to help you get the most out of the ideas involved, I would like to begin by asking you the reader to put off reading this paper now. I request that you look for some images in everyday media that relate to your area of science. Chemical formulae, drawings of atoms, or references to evolution or energy may be suitable. This is exactly how the classroom activity I am suggesting would begin. Now record one comment that describes your first reaction on seeing each item (there is space in the table at the end of this article, which has a worksheet that you can fill in as you read this paper, as an example of the type of meaning-making worksheet that is of use in the classroom). I will come back to these responses a little later. You can find some advertising images at these web addresses: http://www.tomsporer.de/assets/images/ PROJECT_NIVEA_DNAGE_SMALL04.jpg http://www.goswitch.com.au/green-energy http://www.greenadvertisinglaw.com/10-waysto-avoid-making-suspect-green-advertisingclaims.html As science teachers we are comfortable with and literate in science terminology and processes to a higher degree than the average person; so we can deconstruct the use of science in items in the media, advertising and everyday contexts. Being knowledgeable in science, or even fully scientifically literate – if that is at all possible (see Shamos, 1995) – does not necessarily mean that we are protected from the powerful effects of advertising, or always avoid the ‘consumer traps’ set by clever marketing. I suggest looking to the ABC television program The Gruen Transfer for an interesting take on this. Even experts can become enculturated (or indoctrinated) to accepting whatever advertisers and marketing put before us. Appealing to wishful thinking, selfish reasoning and selective use of factual information can mislead or help us come to surprising conclusions at times, which on reflection we may wonder ‘How did I think that?’ As a good example I suggest you go to The Social Issues Research Centre website that ‘foster the image of…a heavyweight research body,’ as Annibel Ferriman wrote in the British Medical Journal in 1999 (vol319, p716). It is run by the PR marketing company MCM Research, which used to announce on its website: ‘Do your PR initiatives sometimes look too much like PR initiatives? MCM conducts psychological research on the positive aspects of your business…. The results do not read like PR.’ David Miller, New Scientist, 26 July 2008. Despite this claim the site is worth a visit as a reference for science teaching, not just as an example of ‘bad science’. On this site a timeline of developments in ‘science’ related to health issues is an excellent resource for teaching. http://www.sirc.org/timeline/timeline_front. shtml. Following is an example accessed from the timeline. July 2003 Dairy diet may prevent asthma Young children who regularly eat products containing milk fat are less likely to develop asthma, research suggests. Scientists say the finding provides strong evidence that while asthma may, in part, be a genetic condition, it is certainly influenced by lifestyle factors too. A team from the Dutch National Institute of Public Health and the Environment analysed the diet of nearly 3,000 two-year-olds. They found that by the age of three, those who had eaten full cream milk and butter on a daily basis were less likely to have developed symptoms of asthma. Daily consumption of brown bread was also associated with lower rates of asthma. (Source: http://www.sirc.org/timeline/2003.shtml) Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 11 Consumer science beyond testing (continued) Comments on a linked article in the Guardian newspaper entitled ‘The truth about juice’ prompted many comments from the readership about the poor science in the above study. Below is just one example: ‘The author is absolutely right and many posts have misinterpreted the article. Firstly, there is a difference between correlation and causality. Secondly, where is the experimental data to demonstrate the validity of any of these claims? There has been such a blurring of the scientific method in the public mind (as well as a perversion of logic) that people are now convinced about anything by a whizzy graph on TV.’ (Reader comment on ‘The truth about juice’ Guardian newspaper.) What are food groups in ‘scientific’ and ‘everyday’ thinking? group. By the 1950s school children were taught there were four basic food groups (De Puis, 2002). Dairy had become one of these. Each time the ‘dietary recommendation’ is reviewed, lobby groups from marketing sectors work hard for their products. Refer to the history of Nutrition Guidance (USA) below for an example of how groupings evolve. Figure 1: A standard food pyramid Food groups are a good example of ‘science’ that is in everyday culture that are more likely to be culturally determined than ‘scientific’ food groups. Many food groups in science textbooks also have little resemblance to chemical food categories. For a collection of international food groupings and nutritional recommendations go to http:// archives.starbulletin.com/1999/04/21/features/ story1.html. On this site you will find examples from Japan, Phillipines, Netherlands, Canada, Israel and Great Britain. As a specific, and non-trivial example with far reaching effects, let me put before you my take on the story of how milk came to be considered a food group. This is a great example of how culture and history, and everyday rather than scientific thinking can have more to do with what is accepted ‘scientific knowledge’ than ‘objective’ data (Vygotsky, 1986). In the 1930s the milk marketing board in the USA introduced the idea that milk is a food group as an advertising campaign. You would have to say this is one of the most successful campaigns in history. Milk is now shown in most good food pyramids as a food group in science textbooks, research documents and product information. Back in the 1930s there were 12 recognized food groups and lobbying from the Milk Marketing Board helped to get milk, eggs and butter classed as one major To a large extent, still today, the status of milk as recommended for daily intake in a ‘healthy diet’ is based far more on product marketing, finances and agriculture than health. As far back as the 1960s research by the World Health Organization was showing that milk was unsuitable for a large proportion of many cultural groups. Changing the good food guides to more scientific chemistry/nutrition based groups, away from the current cultural-historic and economically based one is proving a very difficult task, made more difficult by constant lobbying of interest groups. Collecting cultural images of the ways foods are grouped from everyday life may be a good way to inform our learner that food groups are not fixed, or necessarily based in chemistry, health or known best dietetic practice. 12 Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 History of Nutrition Guideance (USA) 1916 5 groups Milk & Meat Vegetables & Fruits Cereals 1933 12 groups Milk Lean Meat, Poultry & Fish Eggs Dry Beans, Peas & Nuts Tomatos & Citrus Fruits Leafy Green & Yellow Veg Other Veg & Fruits Potatos & Sweet Potatos Flours & Cereals Other Fats 1942 “Basic seven” Meat, Milk & Poultry, Milk Fish, Eggs, Products Dried Peas & Beans Bread, Flour & Cereals Butter & Fortified Margarine Oranges, Tomatos & Grapefruits Green & Yellow Veg Potatos & Other Veg & Fruits Meat, Poultry, Milk & 1956 Fish, Eggs, Milk Dried “Basic four” Products Beans & Nuts Fruits & Vegetables Grains Meat, Poultry, Milk, Fish, Eggs, Yoghurt Dried & Cheese Beans & Nuts Fruits & Vegetables Grains 1992 “Food Guide Pyramid” Fats & Fat Foods Butter Sugars & Sugary Foods Sugars Fats & Sweets Source: Based on information from http://www.pcrm.org/magazine/GM97Autumn?GM97Autumn2.html What is consumer science? When I think of consumer science my thoughts, like many science teachers, usually go to ‘controlled scientific research’ into product claims. This idealized testing can be very informative, particularly when conducted independently, such as you might see in Choice magazine (www.choice.com.au). An example that is always popular is Can dark chocolate be ethical, good for you and delicious? published online November 2008. A panel of experts rated 22 brands of chocolate and 65 everyday tasters also rated 15 of the chocolates. Differences between criteria used by experts and that used by novices is an interesting take on this subject that comes out very clearly in this research. Selling products with consumer testing The type of ‘controlled scientific tests’ product testing is often used as a way of selling a product – the image of long flowing hair (on a beautiful model) in a shampoo add or the white coated scientist ‘proving’ that a product is better are typical images that come to mind. It comes as no surprise that the design and use of these tests can make them anything but ‘objective’. It is now clear for instance that pharmaceutical companies are more likely to fund and/or publish research that shows the efficacy of their products than research that shows the opposite. Having students come up with controlled scientific product tests can be a valuable approach in science: one that I support and think well worth the effort of pursuing. Students Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 13 Consumer science beyond testing (continued) come up with many ingenious methods of collecting data, and grapple with the very value laden problems of designing ‘controlled tests’ and collecting ‘objective measurements’. These traditional scientific consumer tests as used in advertising co-opt scientific language, and confuse correlation and causation in interpretation. Take for example this product described in New Scientist feedback page. ‘myth busting’ coke ads get a reality check The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission yesterday ordered Coco-Cola to publish corrections in newspapers around the country over its ‘motherhood and myth-busting’ campaign last year...the ad had potential to mislead consumers by suggesting Coco-Cola could not contribute to weight gain, obesity and tooth decay. Daniella Miletic, Consumer affairs reporter The Age Friday April 3, 2009 page 3. Advertising arguments and ‘pseudoscience’ On television and in papers each day, in all forms of media, science terminology is used, co-opted and turned into everyday language in product advertising and news reports. ‘Green products’ are everywhere. Cars are now environmentally friendly with ‘low carbon emissions’ and organic products are ‘more natural’. You have already reacted to a small set of such advertisements. The process of science is co-opted to the interests of the producers; sometimes amusingly due to the lack of real ‘science’. What do you notice? Let’s return now to your comments made at the beginning of this article in response to advertisements using ‘science’ and ‘pseudoscience’ claims. What did you notice in each case? What took your interest? Can you describe your response as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ response towards the product or the advertisement? Were you focused on the accuracy? Or were you simply reminded of what you need to buy next time? Or did an image influence you (such as flowing hair in a shampoo advertisement)? We all focus on different things, and although you have a cue from the article’s title, I 14 Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 tried to present the idea of looking at the advertisements before I flavoured your thoughts too much. Each response has value and could lead us to interesting areas of shared thoughts and meanings. What I do as teacher with each and every response is important to learners both personally and to their learning. What each person thinks about these advertisements and the meanings raised by others are also important and can help progress learning. We have devoted a lot of our time here to looking at these responses – developing a social and individual space where ideas can develop and grow (Wellington and Osborne, 2001). Students as everyday consumers The students in our science classes are already experts in making decisions about consumer products. They have spent many years considering prices and value for money when buying an extensive range of products. As science teachers we can add to this expertise by helping them better understand some of the science used in designing advertising and testing products. Too often science content is seen as outside the everyday life of our students. Some of the science terminology being used by advertisers includes words with specific technical, scientific meaning appropriated by society to come to have alternate everyday meaning. Polyunsaturated, cholesterol and even extra-virgin olive oil become loaded with cultural meaning and move from being specific terms that have meaning as a chemical, to desirable and undesirable with health effects unlinked from the research that demonstrates their roles in the body or the processes of metabolism. The terms become everyday entities, isolated from the meaning that the science that developed it, has given it. We often think of science classes as providing terminology and giving learners access to correct science. Unless the relationship between the ‘everyday’ and the classroom ‘scientific’ are clearly delineated in science classes the confusion between the two will persist, and unhelpfully, be enhanced by the barrage of ‘science’ used by marketers. Thus I see a great opportunity for us as science teachers to enhance students’ functional scientific literacy by using consumer product information, as well as scientific consumer testing, as a vehicle for students to become more informed consumers. According to Vygotsky (1987) everyday concepts lay the foundation of learning the scientific. One method of making science more relevant to everyday life is to incorporate everyday experiences into science learning (Aikenhead, 2006). Ideas expressed by Lee in Tobin and Roth (2007) are also worth considering here, where differences between informal and formal settings are included as well as free choice and mandated content. I will consider one consumer issue covered on an Insight program aired on SBS in 2008 related to recent melamine and other poisoning events and product safety in general. Insight into consumer issues In considering product safety many scientific terms are used in social discussions, that may have specific meaning to the chemists and other scientists involved but have many and varied companion meanings in society. In the case of melamine in baby milk causing deaths, the word melamine is used – as a word for a poison – without any chemical scientific significance. This is a case in which people are dealing with complex science to understand what happened in a social disaster, and extremely surprised that consumers are not better protected by our system. We expect products to be safe. However our knowledge of the sea of toxic chemicals we live in is very poor. Programs such as Insight and current news items as well as product advertising can be a great starting point for a range of science topics. The fact that a current social issue is at the heart of the topic makes the Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 15 Consumer science beyond testing (continued) terminology more culturally available, brings in a range of social, emotional and aesthetic meanings, can make the range of ideas ‘messy’ in terms of the scientific investigations, but this must be viewed as a strength not a weakness. The very fact that the topic has emotional meaning provides greater chance of personal transformations occurring in the learning. Everyday science word use influences meanings Science terminology and processes are used extensively on products and in advertising today. Much of this language is science content based, and often extremely technical in nature. Advertising takes words, often out of context, and make them sound powerful. From microlipids in face lotions, to isotonic and hypertonic sport drinks, and phosphate free advertising of washing powders with enzyme action ‘for clothes whiter than white’ we have scientific sounding words used in ways that are designed to convince but not inform. In fact for most people in our society these are the only places that they contact this terminology. These words only have meaning in relation to this everyday use. These are both incorrect meanings and socially embedded accepted meanings. Cholesterol becomes a substance that you get in certain foods that causes heart attacks. It is not the same thing as a biochemist’s definition. How close the everyday (or naïve or cultural ideas) can be to the ‘scientific’ has been extensively studied in alternative conceptions research. Constructivist researchers have focused heavily on designing teaching to move the ‘naïve everyday idea’ towards the ‘scientific’. Experience shows this is much harder than had initially been thought. In all areas of science initial ideas are remarkably resistant to change and often remain alongside classroom learning, to come into use in everyday life. These are not misconceptions necessarily, but everyday use of language, some of which existed before the current 16 Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 scientific idea evolved and some appropriated by society for other uses. We all have experience of doing this. We get up in the morning and talk of ‘sunrise’, even though we know full well that it is the Earth turning that has caused the effect. Even physics teachers use the scientific terms ‘energy’ and ‘work’ in our everyday lives in common usage senses, and then switch to a different mode in classrooms, trying to shift our students’ understandings. Jabberwocky: Nonsense with meaning The aesthetic experience of going through changes in understanding is like going into a foreign land, where you do not have a good grasp of the language. Let’s take a look at the classic piece by Lewis Caroll, Jabberwocky. I am not the first to use this example to show what it is like in ‘foreign lands’. ‘Jabberwocky! ‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. (By Lewis Caroll) Now can you say: What was it like in this place? What were the tothes doing? …and the mome raths? How were the borogroves? Despite the fact the words are made up we can take meaning from their presentation in this communication. You can probably answer the above questions quite readily, but what do you know of this fictitious world? What does outgrabe mean? This is a wonderful poem with all its nonsense words placed in language form that make sense. But imagine you are a child in your science class listening to as much ‘nonsense’ coming from the teachers’ mouth describing a world that they simply do not relate to. For without a solid foundation of links between the everyday world and the world of science with language this is what science classrooms can feel like. A slow and active enculturation into the new ideas through all available everyday experiences is vital to scientific understanding being able to develop. The big picture is important at the same time – the two interrelate – the overall world view along with the details together gives a coherent picture. Talking meanings in the classroom Let’s take a look at one simple typical classroom activity to help understand the issue. Imagine you are given a green powder, which your teacher says is a chemical that exists as a solid crystalline compound. (adapted from p 44 of Barnett and Green, 2007). What do you understand by the terms ‘solid’ and ‘compound’? What is a chemical? How many different ways do you use these words? This simple activity could take a long time to complete if the student has a long way to ‘travel’ in developing ‘scientific’ understandings and uses of these words. I am not saying do not do this activity. Nor am I saying the exact activity is not valuable, in fact I think it a very direct route to the heart of the problem I am alluding to. I am simply proposing that the activity requires more concentration and time, including the teacher’s interactions with students, and openness in the class activity to attending to the terminology, and in particular multiple meanings that the learner brings. A shared terminology is needed to progress with the activity if it is to allow desired conceptual development – whether that involves ‘assimilation’ of the concepts into current ideas or ‘accommodation’ of concepts into newer ones. When dealing with terms that students bring in from everyday life, or ones you choose from media or advertisments, it may not be necessary to come to specific shared meanings so much as to allow and encourage examination of meanings and their impacts on how we think about products and issues. ‘Talking ideas into being’ is a powerful learning tool. Each student needs an amount of time to get used to the language, to start tentatively and revisit again and again the ideas, terms and processes to constantly refine understanding, rather than the idea being available immediately as a kind of gestalt shift. Only by being comfortable enough to approach learning in this way, where the aesthetics of the situation are embraced, does true learning occur (Wickman, 2006). The power of advertising I sometimes feel I am the visitor to another world when I sit and listen to advertisments on TV. Marvelous half science, half advertising lingo comes battering at me, convincing me that this product will do the trick for me. The jingle covers the introduction of words that sound powerfully scientific, that sneak directly into my subconscious. Through lulled defenses my hackles often rise, protecting me from accepting what my reasoning self knows to be a sham. According to Dewey and Wittgenstein the human mind is inseparable from history and culture. These are the background to our habits of mind and the places that we encounter customs. “Both Dewey and Wittgenstein strongly opposed the idea that our thinking can be understood as representations of finite states in the world. …Wittgenstein was incessantly reminding us that of how we actually use language as integral to an activity ” (Wickman, 2006). Learning is neither purely in the individual mind, or purely socially influenced. Science learning is impacted by individual and social Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 17 Consumer science beyond testing (continued) cultural realities. Exploring the language in use in activities is where the various companion meanings can be transformed towards desirable outcomes. Conclusion Today bombardments from the media create an enormous cultural force that impacts heavily on students’ lives. In some ways this can have greater influence on their view of ‘what is science’ and ‘scientific’ than any other influence, including our classrooms. By linking into this barrage of experience, including it in our science classroom discourses, we can influence learners’ views of science and science classroom that are meaningful for them, and even encourage students towards a positive aesthetic in science, along with helping inform their consumer practice in everyday lives. Their scientific ‘lifeworld’ can become real and more significant to themselves, their decision making and their real world existence. We can and should be bridging the gap, between the scientific and the everyday, making this border crossing into the land of science easier and more beneficial for our learners (Aikenhead, 2006). In the process we may just help debunk some unsubstantiated beliefs, which can be clearly non- or even antiscientific. This approach has a ‘companion meaning’ (Roberts and Ostman, 1998) of valuing the cultural starting point of the learner and enculturate them into a more scientific way of being. Talking multiple meanings of science in advertising can thus influence both cognitive processes in consumer literacy and more importantly perhaps for science teachers the overall aesthetic for learners of being in science classrooms and doing science. 18 Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 References ABC (2008) The Gruen Transfer. Aikenhead, Glen S (2006) Science education for everyday life: Evidence -based practice, Teachers College Press, New York. Barnett, Richard and Green, Derek (2007) Scientific enquiry skills, Book 1, Instant Lessons, Blake Education and Brilliant Publications, Clayton South. Bearison, David J. and Dorval, Bruce (2002) Collaborative cognition: Children negotiating ways of knowing, Ablex Publishing, Westport, CT. Choice magazine online www.choice.com.au Commonwealth of Australia (2008) Consumer and financial literacy, Curriculum corporation, Carlton. Roberts, Douglas A. and Ostman. Leif (1998) Problems of meaning in science curriculum Teachers College Press, New York. DuPuis E. Melanie (2002) .Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink. New York: New York University Press. Jakab, Cheryl and Keystone, David (1997) Our best guess, Science Infotexts, Nelson ITP, South Melbourne. Roth, Wolff-Michael (2005) Talking science: Language and learning in science classrooms, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc, Maryland. SBS Insight screened Tuesday 7.30. Shamos, Morris H (1995) The myth of scientific literacy, Rutgers University Press, New Jersey. Sutton, Clive (1992) Words, Science and Learning. Open University Press, Buckingham. Vygotsky, L (1986) Thought and language, MIT Press London (first published in Russian in 1934). Wellington, Jerry and Osborne, Jonathan (2001) Language and literacy in science education, Open University Press, Buckingham. Wickman, Per-Olof (2006) Aesthetic experience in Science education: learning and meaning-making as situated talk and action, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey. Meaning making Activity Record sheet Activity Response Metacognition: Comments / I am thinking… 1. My responses 2. Food groups List the major food groups 3. Potato chip test Plan 4. Significant features What did I notice? 5. Insight 6. Jabberwocky as a foreign land What sort of day was it? Describe the conditions? How do the toves move? 7. Talking meanings Solid Compound Chemical Let’s Find Out Vol 26 • No. 2 • 2009 19