International Marketing

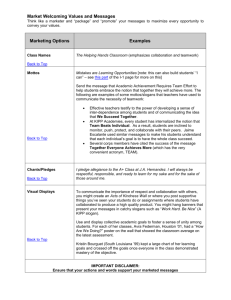

advertisement