UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ

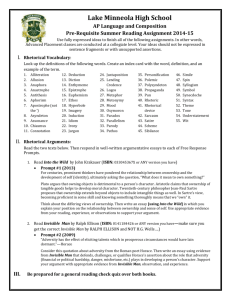

advertisement