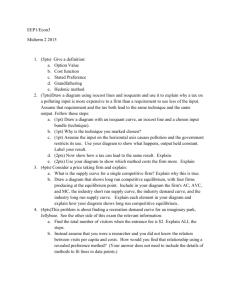

Demand, Supply, and Market Equilibrium

advertisement