An Integrative Definition of Leadership

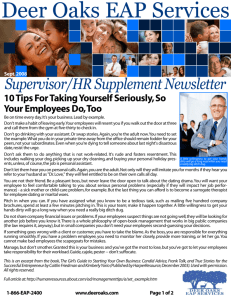

advertisement