- Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

advertisement

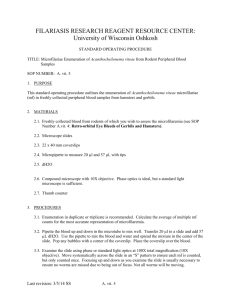

Clinical and immunologic observations in patients who stop venom immunotherapy David B. K. Golden, M.D., Kevin Johnson, B.S., Bonnie I. Addison, Martin D. Valentine, M.D., Anne Kagey-Sobotka, Ph.D., and Lawrence M. Lichtenstein, M.D., Ph.D. Baltimore, Md. B.A., It is currently recommended that venom immunotherapy (VIT) be continued as long as the sensitivity persists (indicated by positive venom skin tests or RAST). In this pilot study, we performed a retrospective survey of the clinical and immunologic effects of stopping VIT. The 82 patients studied had received maintenance VIT for a mean of 14 months and had stopped VIT a mean of 43 months before evaluation. Subsequent “field” stings in 28 patients caused systemic reactions in six cases (22%), which is significantly higher than the 1% to 3% systemic reaction rate in patients who remain on maintenance VIT. The 22% reaction rate is a minimal estimate caused by loss of venom sensitivity in some patients and residual venom-spectjic IgG antibody levels in others. Reevaluation of venom skin tests and IgG levels was possible in 43 patients. A tenfold decline from before VIT skin test results was observed in 27 patients (63%). Skin tests remained clearly positive in 32143 (74%) became weakly positive in 9143 (21 o/o),and 2143 (5%) became negative. The IgG level declinedfiom typical maintenance levels before stopping VIT (mean 7.2 ? I .2 pglml) to levels typical of untreated patients at the time of retesting (mean I .95 ? 0.3 pglml). Despite the marked fall of IgG antibody, one third of the patients still had levels in the average range observed in patients receiving maintenance VIT. We conclude that there is a substantial risk of anaphylactic sting reaction if VIT is stopped while venom sensitivity persists. (J ALLERGYCLIN IMMUNOL77:43542, 1986.) Systemic allergic reactions to insect stings can be completely preventedin virtually all patientsreceiving Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy.I, * Investigations during the past decadehave helped to clarify the indications for VIT and to define the optimal methods for induction, maintenance,and monitoring of clinical protection. However, the required duration of such treatment is uncertain and is of some concern to patients and physicians alike becauseof the inconvenience and cost of maintenanceVIT during a period of years or decades. Although it is currently recommendedthat maintenanceVIT be continued as long as the venom hypersensitivity persists, it has recently becomeevident From The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Clinical Immunology, The Good Samaritan Hospital, Baltimore, Md. Supported by Grant AI08270 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Received for publication Sept. 24, 1984. Accepted for publication Aug. 1, 1985. Reprint requests: David B. K. Golden, M.D., Johns Hopkins Wniversity School of Medicine, Dept. of Medicine, Div. of Clinical Immunology, The Good SamaritanHospital, 5601 Loch Raven Blvd., Baltimore, MD 21239. Publication No. 633 from the O’Neill Research Laboratories, The Good Samaritan Hospital, Baltimore, Md. Abbreviations used VIT: Venom immunotherapy MVV: Mixed vespid venom PWV: Polistes wasp venom HBV: Honeybee venom YJV: Yellow jacket venom that many patientsare stoppingtreatmentwith or without the consentof their physicians. We know the clinical and immunologic resultsof long-term venomtherapy but not the outcomeof stoppingtreatment.During 5 years of maintenanceVIT, the venom-specific IgG antibody level is well *maintained,and clinical protection remainsin the rangeof 98%.3.4Venom-specific IgE antibody levels and skin test sensitivity both decline steadily with time in most patients but rarely become entirely negative.3-6Since antivenom IgG levels fall to baseline6 months after a sting, whereas venom sensitivity persists for years,3.’ the potential risk of stopping VIT would appear to be great. We therefore set out to document the clinical and immunologic sequelaeto stopping VIT. We report here the first phaseof these studies that involved a retrospective survey for clinical and immunologic followup of patients who stoppedtreatment (dropouts). Our 435 436 Golden et al. J. ALLERGY TABLE f. Sting reactions after VIT was stopped -___ stirlgs RbsaiQns patients N Systemic Large local NORC 2x 6 (22%) 9 (32%) 13 (46%) 36 7 (19%) II (31%) 18 (507c) aim was to estimate the risk of sting reaction before proceeding with a formal prospective study. N?ETtiOUS Wc identified 125 patients from our records who had achievedmaintenancedosesof Hymenopteravenom during at leastb monthsof treatmentand had subsequentlystopped treatmentagainstour advice. Eighty-two patientsresponded tt) a questionnaire, and 43 of these patients were observed for reevaluation by venom skin testsand a blood samplefor determinations of venom-specific antibody levels. The 82 patients who respondedto the survey had been treatedwith full-dose maintenanceVI’J for a meanof 14 months (range 2 to 44 months) and had stopped treatment a mean of 43 months (range 9 to 79 months) before reevaluation. VI? included all venoms to which the patient originally demonstrated positive skin tests, except that PWV was often excluded becauseof unavailability (before 1978) and its cross-reactivity with the other vespid venoms. Thirty-seven patients had received MVV; 17. MVV and PWV; nine. HHV; eight, HBV and MVV: four. HBV, MVV. and PWV: two. HBV. YJV, and PWV: one. HBV and YJV: three. YJV; and enc. PWV only. The meanageof these82 patients was 41 years. and the maleifcmale ratio was 3 : 1. Twentyeight ol’ these dropouts had been stung at lcast 12 months after stopping VIT (mean 36 months, range 12 to 72 months). Thesepatients did not differ significantly from the patients who were not stung with respectto age, sex ratio, duration of maintenanceVIT, severity of pretreatmentsting reaction. or degreeof sensitivity on pretreatmentskin tests. The 43 patients who presentedto the Allergy Center for retestingrepresentedsimilar proportions of patientswho had been stung !15/28) and of those who were not stung (28i 54). The patients who were retesteddid not differ significantly from those who were not available for retesting with respectto any of the variables listed above. Intfadermal venom skin tests were performed with all five commercial Hymenoptera venom protein extracts at concentrationsup to and including t .Opglml. Venom skin tests were graded according to the method of Norman.’ Venom-specific I@ antibody levels were measuredby the StaphyIococcalprotein A solid-phaseradioimmunoassay previously described.” RESULTS Table I illustrates the outcome of insect stings that occurred in these patients at least 12 months after stopping VIT. Thirty-six stings occurred in 28 pa- CLIN. IMMUNOL. MARCH 1966 tients, causing seven systemic reactions in six of the patients (22%). To put these data into perspective, Table II iilustrates a comparison of the reaction rate in the patients who stopped VIT to that of treated and untreated patients. In a retrospective survey. concurrent controls could not, of course, be planned. Most investigators have found a systemic sting reaction rate of 1% to 3% in patients on long-term maintenance venom therapy. I. ’ We perform sting challenges every summer on patient volunteers as part of our monitoring of long-term venom treatment. For comparison with the patients who had stopped therapy, we selected the patients we had deliberately stung in the summer of this survey who had started treatment between 1978 to 1980 and had therefore been followed for the same length of time as the dropouts. The systemic reaction rate in this group of 30 patients who had continued to receive maintenance immunotherapy for 3 to 5 years was significantly less than the rate observed in the 28 patients who had stopped treatment (p < 0.04). The rate of systemic reactions in untreated patients has been reported in the range of 30% to 60% by many investigators. The highest estimates of 6 1% systemic reaction rate in untreated patients, Hunt et al.“’ and Settipane and Chafee, ’ ’ are signficantly higher than the rate observed in our dropouts. However, the systemic reaction rates reported by Parker et al.,” Dvorin et al. ,’ and Blaauw et al.” in their separate investigations were not significantly different from the reaction rate in the patients who stopped venom therapy. More than one sting episode had occurred in seven of the patients surveyed. Five had only large local reactions or no reaction to all stings. One patient (Table III) had two stings, both of which caused severe anaphylaxis with unconsciousness 13 months and 35 months after stopping venom therapy. Another patient (Table IV) had been treated with HBV and MVV based on his skin test sensitivities, but all his systemic reactions had been from yellow jacket stings. A honeybee sting 43 months after stopping treatment caused no systemic reaction. but a yellow jacket sting 45 months after therapy caused a severe systemic rcaction. His skin tests 45 months after therapy was stopped were negative for honeybee venom and positive for the vespid venoms. It was not possible in most cases to identify the culprit with absolute certainty. We cannot be sure that all patients were stung with insects relevant to their sensitivity and treatment. In four cases (of 28 patients stung) the patient was quite uncertain of the culprit (two YJ allergic, 1 PW, and 1 HB/MV). The other 24 patients were confident of the identification. YJ was indicated by all 14 MVand all six MV/PW-treated patients; four beekeepers were certain of HB stings. As illustrated in Table III, there was no consistent VOLUME NUMBER TABLE 77 3 Observations II. Sting reactions in allergic in patients who stop venom immunotherapy 437 patients N Patients Systemic 28 30 VIT stopped Maintenance VIT Untreated Hunt et al.‘” Settipaneand Chafee” Parkeret al.‘* Dvorin et al.’ Blaauw et al.13 6 1 23 119 16 19 85 % P* 22 3 co.04 14 61 72 61 7 8 44 <0.005 <O.ool CO.20 CO.20 CO.40 42 21 23 *Comparedto patientswho stoppedVIT by Fisher’sexacttest. TABLE 111.Systemic reactions in patients who stopped VIT Reaction Duration* of VIT (mo) 4 Timet of VIT to sting lmol Before VIT 35 U&aria, dizziness, dyspnea Urticaria, dizziness, dyspnea Urticaria Urticaria, angioedema,dyspnea, dizziness Angioedema, throat tightness, dizziness Urticaria, dyspnea,dizziness, hypotension Urticaria, unconsciousness, dyspnea 13 5 31 45 4 27 2 36 21 23 12 After VIT Urticaria, dyspnea, unconsciousness Urticaria, dyspnea, unconsciousness Dyspnea, lightheadedness Urticaria Angioedema, throat tightness, dyspnea, dizziness Urticaria, throat tightness Generalized erythema and pruritus *Durationof full-dosemaintenance VIT. tTime whenVIT wasstoppedto sting. tendency for the systemic reactions in these six patients to be either less severe or more severe after therapy than they had been before. Sting reactions also appeared to be unrelated to the time elapsed after therapy stopped. The duration of maintenance VIT was less than 2 years in 22/28 patients stung. No conclusion can be made about the reactivity of patients after prolonged VIT, but the two reactors who had had more prolonged therapy had the mildest posttherapy sting reactions. Fig. 1 presents the severity of sting reactions after stopping venom therapy as a function of the pretreatment sting reaction in all 28 patients who had been reshmg. Susceptibility to systemic sting reactions after stopping treatment did not demonstrate any correlation with the severity of reactions that occurred before VIT. The complete characteristics of the 15 patients who had been stung after stopping VIT and were subsequently available for reassessment are presented in Table IV. Once again, the severity of sting reactions before VIT was in no way predictive of the response to stings after stopping VIT. The results of retesting for venom-specific IgG antibodies and venom skin test sensitivity are presented with the time of retesting (months after therapy was stopped). As expected, the IgG level was in the low range in two of the three systemic reactors, and the third systemic reactor had been stung just a few weeks before testing, which may have boosted the IgG level. The two patients with the strongest skin test sensitivity both had systemic reactions when they were stung after stopping VIT; the third systemic reactor had relatively low skin test sensitivity but had not declined in sensitivity from the pretreatment level. In the 43 patients who were available for retesting, venom skin tests were performed with all five commercial Hymenoptera venoms. All patients had been originally positive (2 + at 1.0 kg/ml or less) to at least one of the venoms. We have excluded from the analysis the results for PWVs, since not all patients had been originally tested with PWV before its commercial production. Table V presents the skin test results for the venoms to which each patient had originally been sensitive and treated. Results are also presented for the patient as a whole, in which the skin 438 Golden J. ALLERGY et al. TABLE IV. Characteristics of patients stung after VIT was stopped rt3mtion grade* Ek#forw MT Aftw 3 4 2 4 5 4 o* 5 3 3 2 5 5 4 2 Antivenom Times WT 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 i 1 1 I 2 3 4 Receiving 19 29 13 51 26 37 42 IS 38 33 24 40 36 12 45 “0 -- no reaction (before VIT indicates this was vascular symptoms; 4 = severe respiratory or ‘Concentration of venom required to elicit a 21 0 indicates negative. fh&nths elapsed since VIT was stopped to time PMonths elapsed since VIT was stopped to time VIT 25.4 6.1 4.1 NA NA 15.7 NA 7.2 15.6 2.6 32.8 7.4 16.3 21.3 3.0 CLIN. IMMUNOL. MARCH 1986 and then reassessed IgG (Ccglml) Venom After VIT Time5 3.5 4.5 0.9 0.6 2.0 0.9 0.2 1.9 3.4 1.6 22.5 1.1 5.4 3.5 1.3 40 43 46 52 50 39 68 63 39 33 30 54 37 49 46 Before skin testt After VIT VIT 0.1 0.01 0.1 1.0 0.1 0.1 0.1 1.0 0.1 0.1 1.0 0.1 0.01 1.0 1+ I .o I+ 1.0 1.0 0 1.0 1.0 I.0 I+ 1.0 0.1 1.0 0.1 1.0 0.01 not primary culprit): I 7 large local: 2 = cutaneous systemic; 3 = mild respiratory or vascular symptoms; 5 = unconsciousness or respiratory arrest. grade skin test reaction (microgram per milliterj; 1 + indicates I + grade at 1.O pgiml: of subsequent sting. of reevaluation of antivenom IgC; and venom skin tests. TABLE V. Venom skin test results Reaction Hymenoptera venom HHV YJ\. YHL WFHV Total skin tests Patients’i N 12 35 33 32 11: 43 10 x -Decline* II 24 18 21 x4 (75%) 27 (63%) grade at 1.0 pglml 0 1+ 2+ 3 8 3 21 (19%) 2 (5%) 4 4 9 7 24 (21%) 9 (21%) 2 28 16 21 67 (60%) 32 (74%) 6 YH =: Yellow hornet: WFH 1 White-faced homer. *Tenfold decline in sensitivity equals at least a tenfold increase in the venom concentration required to elicit a 2 i t0verall degree of patient sensitivity equals skin test eliciting strongest reaction. test eliciting the strongest reaction is taken as an indicator of the patient’s overall degree of sensitivity. There was at least a tenfold decline in sensitivity (i.e., at teast a tenfold increase in the venom concentration required to elicit a 2 + reaction) in 84 of the 112 skin tests (75%). These results include skin test results that had declined to become entirely negative, which occurred in 2 1 of 112 skin tests ( 19%). A decline of at least tenfold in overall skin test sensitivity was observed in 27 of the 43 patients (63%). The development of a negative skin test to any individual venom was not uncommon, although only two of 43 patients reaction. (5%) had become entirely skin test negative to all venoms. This decline or loss of sensitivity was most frequent with honeybee venom whether or not the patient was sensitive to other venoms, and was somewhat more common with yellow hornet venom than with YJV or white-hornet venoms. A clear-cut positive reaction of at least 2 + to a concentration of 1.O kg/ml was observed in 67 of 112 skin tests (60%), and 32 of 43 patients (74%) maintained at least one such clear-cut positive skin test. Twenty-one percent of the skin tests, and patients, became only weakly positive (1 + at 1 p,g/ml). VOLUME NUMBER 77 3 Observations in patients who stop venom e---a 70- . 50 immunotherapy Not 439 stung No reaction 0---o Large loco I D----0 Systemic - 30- . ? 0 2 e E IO- z 3- : I F z 75 I .o0.7 - 2 PRE-VI 3 4 T REACTION 5 GRADE Fig. 1 Severity of insect-sting reactions in 28 individual patients before beginning VI1 and after VIT was stopped. Reaction grades: 0, no reaction; 1, large local reaction; 2, cutaneous systemic reaction; 3, mild respiratory and/or vascular systemic reaction; 4, moderately severe respiratory and/or vascular systemic reaction; 5, severe systemic reaction with unconsciousness or respiratory arrest. The fate of venom-specific IgG antibody levels when immunotherapy was stopped could be determined in 31 patients for whom paired serum samples were available. Of these, 26 were yellow jacket IgG measurements(19 patients treated with MVV, five with MVV and PWV, and two with YJV), and five were honeybeeIgG levels in patientstreatedonly with HBV. Three of the vespid venom-treated patients had also beenimmunized with HBV but had indicated that all their stings had been from yellow jackets; HBVIgG levels were not available in these three patients. The first sample in each case was to reflect the level of IgG antibodies at the time that VIT was stopped, but blood sampleswere often not available from the actual date of the last venom injection. The IgG antibody responseto our standardmodified rush therapeutic regimen is known to rise to a peak level within 2 to 4 months and decline somewhat to the steadystate maintenancelevel in 6 to 9 months. This level is well maintained in most casesduring subsequent years of maintenancetreatment. Of the 31 paired serum samples analyzed, 23 of the sampleshad been drawn from patients receiving therapy after 1% to 5 years of treatment and were considered to reflect steady-statemaintenance levels of IgG; 18 of these were drawn 0 to 6 months before therapy stopped, four were drawn from 7 to 12 monthsbefore stopping, and one was drawn 18 months before stopping (but 3 0.5 0.3- \ I , 0 I I2 TIME SINCE I 24 VENOM I 36 THERAPY I 46 I 60 I 72 STOPPEDhanttd Fig. 2 Venom-specific IgG antibody levels (microgram per milliliter) in 31 individual patients listed before VIT was stopped, and as a function of the time elapsed (months) after venom therapy was stopped. The reaction to an insect sting after VIT was stopped (if any) is indicated for each patient. years into treatment). The other eight samplesfrom patients receiving therapy were drawn 0 to 6 months before stopping treatment, but thesewere only 3 to 6 months into maintenancetreatment and may reflect peak IgG levels in early maintenancetherapy. The 31 paired IgG antibody results are presented in Fig. 2 for each of the individual patients and are plotted as a function of the time elapsed since treatment was stopped. The outcome of stings after VIT, if any, is presentedfor each patient. A few patients demonstratedonly a small drop in IgG, but in general a marked decreasehad occurred. There was no difference in the rate of decline of IgG nor in the mean IgG level at the time of retesting between those patients who had been stung in the interim and those who had not been. The rate of decline of venomspecific IgG antibody levels can only be estimated from these data. The mean IgG levels are plotted in Fig. 3 for all 31 patients before VIT was stoppedand for three subsetsof these patients according to the time elapsed between stopping treatment and retesting. The meanIgG level before treatmentwas stopped (7.2 ? 1.2 pg/ml) was the sameas the averagelevel observed during routine maintenance VIT.3, 4 The 440 Golden J. ALLERGY et al. i- ! c 1 24 12 TIME SINCE VENOM THERAPY 4 1 I 36 48 60 STOPPED hIWlkr) Fig. 3 Geometric mean venom-specific IgG antibody levels ( ? SEM) in microgram per milliliter, listed for the whole group before VIT was stopped, and for three subgroups of patients after venom therapy had been stopped for a mean of 24, 42, or 56 months. Dashed lines depict two hypothetical decay curves for IgG. mean IgG level at the time of retesting of patients not receiving VIT ( 1.95 2: 0.3 Fg/ml) was typical of untreated sting-allergic patients.’ ” There was no difference in the mean IgG levels in the subgroups of patients who had not been receiving VIT for a mean of 24 months. 42 months, or 56 months, indicating that the IgG levels had already dropped to a new plateau by the time of retesting. DISCUSSION VII‘ is safe and effective for rapid and long-term protection of susceptible individuals from recurrent systemic allergic sting reactions. It has been recommended that therapy be continued for as long as the venom sensitivity persists. It has become evident that ;I great many patients are stopping VIT with or without the consent of their physicians. These patients give many different rationales for their actions. Those who have been stung while receiving treatment often believe that their clinical protection will continue after they stop treatment. Many other patients believe that their sensitivity has diminished or disappeared and. as a result. that there would be no risk of a systemic reaction to a sting even if they stop treatment. In order to examine the validity of current recommended practice, we have begun a series of investigations designed CLIN. IMMIJNOL. MARCH 1966 to determine whether, or when, VIT can be safely stopped. This first, or pilot phase, involved a retrospective survey of patients who had stopped VIT against our advice (dropouts). Of the 82 patients who responded to the survey, 28 reported having been stung after a mean of 36 months after therapy was stopped (the range was 12 to 72 months after treatment). Several points can be made about the six patients who experienced systemic sting reactions (Table III). Their reactions demonstrated no tendency to be either more severe or less severe than they had been before treatment. This suggests that VII‘ causes no long lasting decrease or increase in the reactivity of the individual. In contrast to children who often have milder reactions on re-stingsI or treated adults who have only minimal symptoms (if any). these dropouts had a very appreciable risk of major anaphylactic reactions. Because of the severity of the reactions, we questioned these six patients as to why they had not returned for reassessment and treatment. Every one of them indicated that the cost and inconvenience of treatment were major deterrents and that they preferred to take their chances with avoidance techniques and adrenalin kits. These systemic sting reactions occurred 12 to 45 months after therapy was stopped, suggesting that the benefits of treatment are lost shortly after therapy is stopped. Whether prolonged VIT might confer longer lasting protection if the treatment is stopped cannot be assessed from the available data. Among the six reactors, the four who had received 2 to 5 months of maintenance VIT had more severe reactions than the two patients who had had 2 1 and 3 1 months of therapy. However, only six of the 28 patients who had been stung had received more than 2 years of maintenance VIT. This study can therefore not evaluate the reactivity of patients after more prolonged VIT. As illustrated in Table II, patients who stop VIT have a significantly greater risk of systemic reactions than patients who continue to receive treatment for the same period of time. The only other estimate of the systemic reaction rate in patients who stop VIT has been by Dvorin et al.’ in the same article in which they reported a reaction rate of 42% in untreated patients. Systemic reactions occurred in 42% of the dropouts (24% of the stings) that was not significantly different from the reaction rate in their untreated group or in our dropouts. Estimates of the systemic reaction rate in untreated, but susceptible patients, have ranged from 27% to 61 G/o.‘,‘-I’ That our estimated 22% risk of systemic reaction in patients who stop VIT was less than many of the estimates for untreated patients is not at all surprising for reasons that have affected many studies of this disease. The 22% figure is almost VOLUME NUMBER 77 3 Observations certainly an underestimate as a result of the reduced reactivity of many patients during a period of years and the likelihood that some stings were by insects to which the individuals were not allergic at the time. Our own observation of a 6 1% risk in untreated patients is the highest of many such observations and, although the observation is significant statistically, comparison with the minimal estimate of 22% for dropouts may exaggerate the difference between these two groups. Furthermore, it is well recognized that patients may react to some stings and not on other occasions, which makes it uncertain whether those who do not react to a challenge sting can be considered safe in the future. The current data are not sufficient in this area for any conclusions. We conclude that, although most had no systemic reaction, the 22% reaction rate in patients who stop venom therapy was not significantly different from most estimates of reactivity in untreated patients and represents a significantly increased risk of serious systemic reactions over patients who continue treatment. The skin test data in Table V provide some insight into the natural history of the disease. Results are presented only for venoms to which the patients were sensitive and immunized. There was a significant decline in sensitivity in 63% of the patients. This decline occurred in almost all honeybee-sensitive patients and was more common with yellow hornet venom than with white-faced hornet venom or YJV. These results are consistent with the cross-reactivity of the vespid venoms in which yellow hornet usually demonstrates the least activity of the three and might therefore be expected to be the first to decline or disappear. In fact, the disappearance of skin test reactivity followed the same tendency to be greater for yellow hornet than for YJV or white-hornet venoms. The disappearance of HBV, sensitivity was significantly more frequent than for YJV (p = 0.005) or white-faced hornet venom (p = 0.015). Honeybee sensitivity diminished and disappeared as commonly in patients with isolated honeybee sensitivity as in those with combined HBV and vespid venom sensitivities, suggesting that the rapid loss of honeybee sensitivity is not simply caused by the low-level cross-reactivity that has been recently described between HBV and YJV.16,” Most importantly, these results demonstrate that many patients would be mistaken to believe that their allergic sensitivity has disappeared while receiving VIT. We should note that the observed decline in skin test sensitivity may be unrelated to VIT and has been observed in untreated patients such as those with large local reactions. ‘* It is unlikely that these changes are due to batch-to-batch differences in venom potency, since no such differences have been observed in com- in patients who stop venom immunotherapy 441 parisons of various lots by skin test or RAST inhibition. The studies of venom-specific IgG antibody levels were quite revealing. The patients who were available for follow-up testing were quite typical of VIT patients in that they had the same mean and range of antivenom IgG levels before the cessation of VIT.3. 4 Once treatment was stopped, the IgG levels declined markedly in virtually all patients. The mean IgG level at the time of reassessment was quite typical of untreated sting-allergic patients.3. I4 These results indicate that any clinical benefit derived from the humoral immune response to VIT is rapidly lost when treatment is stopped. The rate of decline of IgG antibodies cannot be determined from these data, since all of the study patients were reevaluated more than 18 months after stopping treatment, by which time the mean IgG antibody level had already fallen to the level of untreated patients (Fig. 3). As suggested by the dashed lines in Fig. 3, it is not possible to determine whether the fall in IgG occurred rapidly within the first 6 months after treatment stopped, as has been observed in the 6 months after an insect sting in untreated patients,“,’ or whether it declined more gradually between 0 and 24 months. In any case, it is clear that many patients are mistaken if they believe that their immunity will persist when they stop treatment. The skin test and antibody results are also important because they may have some bearing on the observed systemic reaction rate. Among the 15 patients who had been stung and were available for retesting, five patients had skin tests that had decreased to negative or borderline positive. None of these five patients had systemic or large local reactions after VIT was stopped. The systemic reaction rate in dropouts with persistent sensitivity might therefore be much higher than the observed 22% rate, since venom sensitivity becomes borderline or negative in a large proportion. Venom-specific IgG antibody levels are also important in this regard. We have previously reported,“ and continue to observe, that patients receiving VIT in whom the IgG level is >4 pg/ml have a very low risk of systemic reaction to challenge stings (l%), whereas patients with IgG levels <3 pg/ml have a significantly higher risk of reaction of approximately 15%. Examination of Fig. 2 illustrates that despite the marked decrease of IgG levels after cessation of VIT, eight of the 31 patients still had IgG levels >4 pg/ml at the time of reassessment and might therefore have some residual clinical protection as a result of the persistence of blocking antibodies. In fact, Fig. 2 also illustrates that most of the patients who were not stung had IgG levels <3 pg/ml. Once again, the systemic reaction rate might have been distinctly higher if all 442 Golden et al. the subjects had been stung. It therefore appearsthat the 22% reaction rate in the dropouts is a minimal estimate cauSedby the loss of sensitivity and/or residuaI I@ antibody levels in at least 25% of these patients. The results of this retrospective survey lead to several conclusions. The risk of systemic sting reactions in patients who stop VIT is significantly greater than in those who fctllow the recommendedmaintenance treatment schedule. Severe or life-threatening reactions may occur after therapy is stopped. Venom skin test sensitivity declines in most patientsbut disappears completely in only 5% of patients retestedafter 3 to 6 years. Venom-specific IgG antibody levels fall to pretreatment 1eveIsin most patients who stop WT. This pilot study indicates the need for further investigations to answer several remaining questions. The patients in this survey had received maintenanceVIT for an average of 14 months. Since we cannot extrapolate our conclusions to patients who have received prolonged VIT, it would be of interest to study patients who stop treatment after many years. Prospective study of such patients would permit the description of the decay rate of venom-specific IgG antibodies when treatment is stoppedand would permit the evaluation of systemicreaction rates in subgroups of patients on the basis of skin test sensitivity and venom-specificantibody levels at the time of the posttreatment sting. The current article does indicate that we should continue to recommendthat VIT be continued for as long as the sensitivity persists. 1. Golden DBK, Lichtenstein LM: Insect sting allergy. In Smith LH, editor: Cecil textbook of medicine, ed 16. Philadelphia, 1982, WB Saunders Co, p 1805 2. Dvorin DD, Georgitis JW, Reisman RE: Natural history of insect sting anaphylaxis: evaluation of untreated and incompletely treated patients. J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOI. 73:1X8. 1984 (abst) 3. Golden DBK, Kagey-Sobotka A, Hamilton RG. et al: Human immune response to Hymenoptera venoms. J ALLERGY CLIN IMMIJNOL.71:140, 1983 (abst) J. ALLERGYCLIN. IMMUNOL. MARCH1986 4. Golden DBK, Meyers DA, Valentine MD, et al: Clinical reevance of the venom-specific immunoglobulin G antibody level during immunotherapy. J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOL 69:489, 1982 5. Graft DF, Schuberth KC, Kagey-Sobotka A, Kwiterovich KA, Lichtenstein LM, Valentine MD: Immunologic effects of prolonged venom immunotherapy in children. J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOL 71:140, 1983 (abst) 6. Graft DF, Schuberth KC, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al: The dcvelopment of negative skin tests in children treated with venom immunotherapy. J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOI. 73:6I, 1984 7. Light WC, Reisman RE, Shimizu M, Abesman CE: Clinical application of measurements of serum levels of bee venomspecific IgE and IgG. J ALLERGYCLIN I~~u~01.59:247, 1977 8. Norman PS: Skin testing. In Rose NR, Friedman H, editors: Manual of clinical immunology, ed 2. Washington, D. C., 1980. American Society of Microbiology. p 791 9. Hamilton RG, Adkinson NF Jr: Quantitation of antigen-specific immunoglobulin G in human serum. II. Comparison of radioimmunoprecipitation and solid-phase radioimmunoassay techniques for measurement of immunoglobulin G specific for a complex allergen mixture (yellow jacket venom). J ALLERGY CI.IN IMMUNOL 67: 14, 198 I 10. Hunt KJ, Valentine MD, Sobotka AK, et al: A controlled trial of immunotherapy in insect hypersensitivity. N Engl J Med 299:157, 1978 11. Settipane GA, Chafee FH: Natural history of allergy to Hymenoptera. Clin Allergy 9:385, 1979 12. Parker JL, Santrach PJ, Dahlbeg JE, et al: Evaluation of Hymenoptera-sting sensitivity with deliberate sting challenges: inadequacy of present diagnostic methods. J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOI.69:2~, 1982 13. Blaauw PJ, van den Brock MJTB, Smithuis LOMJ: The insect-sting challenge as a ultimate indication for venom immunotherapy. Folia Ailergol Immunol Clinica 30: 141, 1983 14. Golden DBK, Langlois J, Valentine MD, et al: Treatment faiiures with whole body extract therapy of insect sting allergy. JAMA 246:2460, 1981 15. Schuberth KC, Graft DF, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al: Do all children with insect allergy need venom therapy? J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOL 71:140, 1983 (abst) 16. Hoffman DR, Wood CL: Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XI. Isolation of protein allergens from Vespulu maculijrons (yellowjacket) venom. J ALLERGYCLINIMMUNOL 74:93, 1984 17. Reisman RE, Muller UR, Wypych JE, et al: Studies of coexisting honeybee and vespid-venom sensitivities. J ALLERGY CLN IMMUNOL 73:246, 1984 18. Golden DBK, Johnson K, Addison BJ, et al: Evolution of Hymenoptcra venom allergy (HVA). J ALLERGYCLIN IMMUNOI. 73:189. 1984 (abst)