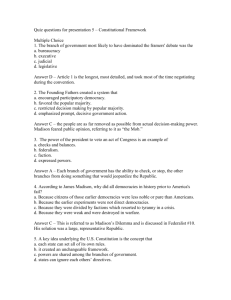

supplement to chapter 27 §6

advertisement