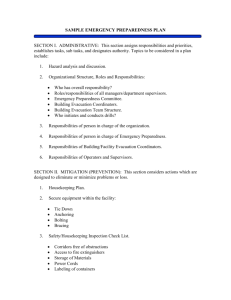

Good practice in emergency preparedness and response

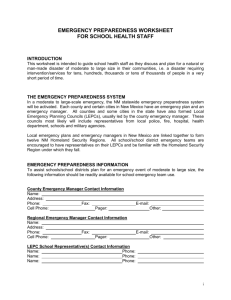

advertisement