Haystacks

Sales

Michael Vernon Guerrero Mendiola

2003

Shared under Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Philippines license.

Some Rights Reserved.

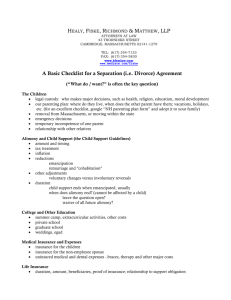

Table of Contents

Acap vs. CA [GR 118114, 7 December 1995] …......... 1

Adalin vs. CA [GR 120191, 10 October 1997] …......... 3

Addison vs. Felix [GR 12342, 3 August 1918] …......... 6

Adelfa Properties vs. CA [GR 111238, 25 January 1995] …......... 9

Agricultural and Home Extension Development Group vs. CA [GR 92310, 3 September 1992] …......... 15

Almendra vs. IAC [GR 75111, 21 November 1991] …......... 17

Ang Yu Asuncion, et.al, vs. CA [GR 109125, 2 December 1994] …......... 20

Angeles vs. Calasanz [GR L-42283, 18 March 1985] …......... 24

Azcona vs. Reyes [GR 39590, 6 February 1934] …......... 27

Aznar vs. Yapdiangco [GR L-18536, 31 March 1965] …......... 29

Babasa vs. CA [GR 124045, 21 May 1998] …......... 31

Bagnas vs. CA [GR 38498, 10 August 1989] …......... 34

Balatbat vs. CA [GR 109410, 28 August 1996] …......... 37

Calimlim-Canullas vs. Fortun [GR 57499, 22 June 1984] …......... 40

Carbonell vs. CA [GR L-29972, 26 January 1976] …......... 42

Carumba vs. CA [GR L-27587, 18 February 1970] …......... 49

Celestino Co vs. Collector of Internal Revenue [GR L-8506, 31 August 1956] …......... 50

Cheng vs. Genato [GR 129760, 29 December 1998] …......... 52

CIR vs. Engineering Equipment and Supply [GR L-27044, 30 June 1975] …......... 58

Coronel vs. CA [GR 103577, 7 October 1996] …......... 62

Coronel vs. Ona [GR 10280, 7 February 1916] …......... 68

Cruz vs. Cabana [GR 56232, 22 June 1984] …......... 71

Cruz vs. Filipinas Investment [GR L-24772, 27 May 1968] …......... 73

Cuyugan vs. Santos …......... [unavailable]

Dagupan Trading vs. Macam [GR L-18497, 31 May 1965] …......... 76

Dalion vs. CA [GR 78903, 28 February 1990] …......... 77

Daguilan vs. IAC [GR L-69970, 28 November 1988] …......... 79

De la Cavada vs. Diaz [GR L-11668, 1 April 1918] …......... 82

Delta Motors Sales vs. Niu Kim Duan [GR 61043, 2 September 1992] …......... 86

Dignos vs. Lumungsod [GR L-59266, 29 February 1988] …......... 87

Dizon vs. CA, 302 SCRA 288 …......... [unavailable]

Doromal vs. CA [GR L-36083, 5 September 1975] …......... 90

Dy vs. CA [GR 92989, 8 July 1991] …......... 93

EDCA Publishing vs. Santos [GR 80298, 26 April 1990] …......... 96

Elisco Tool Manufacturing vs. CA, 308 SCRA 731 (1999) …......... [unavailable]

Engineering and Machinery Corp. vs. CA [GR 52267, 24 January 1996] …......... 99

Equatorial Realty vs. Mayfair Theater [GR 106063, 21 November 1996] …......... 102

Intestate Estate of Emilio Camon; Ereneta vs. Bezore [GR L-29746, 26 November 1973] …......... 109

Heirs of Escanlar, et.al, vs. CA [GR 119777, 23 October 1997] …......... 110

Espiritu vs. Valerio [GR L-18018, 26 December 1963] …......... 116

Estoque vs. Pajimula [GR L-24419, 15 July 1968] …......... 117

Filinvest Credit vs. CA [GR 82508, 29 September 1989] …......... 118

Filipinas Investment vs. Ridad [GR L-27645, 28 November 1969] …......... 121

First Philippine International Bank vs. CA, 252 SCRA (1996) …......... [unavailable]

Froilan vs. Pan-Oriental Shipping Co., 12 SCRA 276 (1964) …......... [unavailable]

Fule vs. CA [GR 112212, 2 March 1998] …......... 124

Gaite vs. Fonacier [GR L-11827, 31 July 1961] …......... 128

Goldenrod Inc, vs. CA [GR 126812, 24 November 1998] …......... 131

Guiang vs. CA [GR 125172, 26 June 1998] …......... 133

J, Schuback & Sons vs. CA [GR 105387, 11 November 1993] …......... 135

Spouses Ladanga vs. CA [GR L-55999, 24 August 1984] …......... 137

Legarda Hermanos vs. Saldana [GR L-26578, 28 January 1974] …......... 138

Levy Hermanos vs. Gervacio [GR 46306, 27 October 1939] …......... 140

Lim vs. CA, 263 SCRA 569 (1996) …......... [unavailable]

Limketkai Sons Milling vs. CA [GR 118509, 1 December 1995] …......... 141

Loyola vs. CA [GR 115734, 23 February 2000] …......... 147

Luzon Brokerage vs. Maritime, 86 SCRA 305 (1978) …......... [unavailable]

Macondray vs. Eustaquio [GR 43683, 16 July 1937] …......... 150

Manila Racing Club vs. Manila Jockey Club [GR L-46533, 28 October 1939] …......... 154

Mapalo vs. Mapalo [GR L-21489 and L-21628, 19 May 1966] …......... 155

Mate vs. CA [G.R, Nos, 120724-25, 21 May 1998] …......... 158

Mclaughin vs. CA, 144 SCRA 693 (1986) …......... [unavailable]

Medina vs. Collector of Internal Revenue [GR L-15113, 28 January 1961] …......... 160

Melliza vs. Iloilo City [GR L-24732, 30 April 1968] …......... 161

Mendoza vs. Kalaw [GR 16420, 12 October 1921] …......... 163

Mindanao Academy vs. Yap [GR L-17681, 26 February 1965] …......... 165

Montilla vs. CA [GR L-47968, 9 May 1988] …......... 168

National Grains Authority vs. IAC [GR 74470, 8 March 1989] …......... 170

Navera vs. CA [GR L-56838, 26 April 1990] …......... 171

Nietes vs. CA, 46 SCRA 654 …......... [unavailable]

Noel vs. CA [GR 59550, 11 January 1995] …......... 176

Spouses Nonato vs. IAC [GR L-67181, 22 November 1985] …......... 179

Nool vs. CA [GR 116635, 24 July 1997] …......... 180

Northern Motors vs. Sapinoso [GR L-28074, 29 May 1970] …......... 184

Odyssey Park Inc, vs. CA, 280 SCRA 253 (1997) …......... [unavailable]

Ong vs. CA [GR 97347, 6 July 1999] …......... 186

Ong vs. Ong [GR L-67888, 8 October 1985] …......... 189

Pangilinan vs. CA, 279 SCRA 590 (1997) …......... [unavailable]

Pasagui vs. Villablanca [GR L-21998, 10 November 1975] …......... 190

Paulmitan vs. CA [GR 61584, 25 November 1992] …......... 191

Philippine Trust Company vs. PNB [GR 16483, 7 December 1921] …......... 194

Philippine Trust Co. vs. Roldan [GR L-8477, 31 May 1956] …......... 198

Pichel vs. Alonzo [GR L-36902, 30 January 1982] …......... 199

PNB vs. CA, 262 SCRA 464 (1995) …......... [unavailable]

Power Commercial and Industrial Corp. vs. CA [GR 119745, 20 June 1997] …......... 203

Puyat & Sons vs. Arco Amusement [GR 47538, 20 June 1941] …......... 206

Quijada vs. CA [GR 126444, 4 December 1998] …......... 208

Quimson vs. Rosete [GR L-2397, 9 August 1950] …......... 211

Quiroga vs. Parsons Hardware [GR 11491, 23 August 1918] …......... 213

Radiowealth Finance vs. Palileo [GR 83432, 20 May 1991] …......... 215

Republic vs. Philippine Development Corp. [GR L-10141, 31 January 1958] …......... 216

Ridad vs. Filipinas Investment [GR L-39806, 27 January 1983] …......... 219

Rillo vs. CA [GR 125347, 19 June 1997] …......... 221

Romero vs. CA [GR 103577, 7 October 1996] …......... 223

Roque vs. Lapuz, 96 SCRA 741 (1980) …......... [unavailable]

Rubias vs. Batiller [GR L-35702, 29 May 1973] …......... 226

Sanchez vs. Rigos [GR L-25494, 14 June 1972] …......... 229

Siy Cong Bieng and Co. vs. Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp. [GR 34655, 5 March 1932] …......... 232

Soriano, et al. vs. Bautista, et al. [GR L-15752, 29 December 1962] …......... 234

Sta. Ana vs. Hernandez [GR L-16394, 17 December 1966] …......... 236

Suria vs. IAC, 151 SCRA 661(1987) …......... [unavailable]

Tagatac vs. Jimenez, 53 OG 3792 (1957) …......... [unavailable]

Tajanlangit vs. Southern Motors [GR L-10789, 28 May 1957] …......... 239

Tanedo vs. CA [GR 104482, 22 January 1996] …......... 241

Torres vs. CA [GR 134559, 9 December 1999] …......... 243

Toyota Shaw vs. CA [GR 116650, 23 May 1995] …......... 246

Universal Food Corp. vs. CA, 33 SCRA 1 (1970) …......... [unavailable]

Uy vs. CA [GR 120465, 9 September 1999] …......... 249

Vallarta vs. CA [GR L-40195, 29 May 1987] …......... 253

Vasquez vs. CA [GR 83759, 12 July 1991] …......... 256

Vda, De Gordon vs. CA [GR L-37831, 23 November 1981] …......... 258

Vda, De Jomoc vs. CA [GR 92871, 2 August 1991] …......... 260

Vda, De Quiambao vs. Manila Motor Company [GR L-17384, 31 October 1961] …......... 262

Velasco vs. CA [GR L-31018, 29 June 1973] …......... 264

Villaflor vs. CA [GR 95694, 9 October 1997] …......... 268

Villamor vs. CA [GR 97332, 10 October 1991] …......... 274

Villonco Realty vs. Bormaheco Inc, [GR L-26872, 25 July 1975] …......... 277

Yao Ka Sin Trading vs. CA, 209 SCRA 763 …......... [unavailable]

Yu Tek vs. Gonzales [GR 9935, 1 February 1915] …......... 283

Yuviengco vs. Dacuycuy, 104 SCRA 668 (1981) …......... [unavailable]

Zayas vs. Luneta Motor Company [GR L-30583, 23 October 1982] …......... 285

This collection contains one hundred three (103)

out of one hundred twenty one (121) assigned cases

summarized in this format by

Michael Vernon M. Guerrero (as a sophomore law student)

during the First Semester, school year 2003-2004

in the Sales class

under Atty. Amado Paolo Dimayuga

at the Arellano University School of Law (AUSL).

Compiled as PDF, July 2011.

Berne Guerrero entered AUSL in June 2002

and eventually graduated from AUSL in 2006.

He passed the Philippine bar examinations immediately after (April 2007).

www.berneguerrero.com

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

[1]

Acap v. CA [G.R. No. 118114. December 7, 1995.]

First Division, Padilla (J): 4 concurring

Facts: The title to Lot 1130 of the Cadastral Survey of Hinigaran, Negros Occidental was evidenced by OCT

R-12179. The lot has an area of 13,720 sq. m. The title was issued and is registered in the name of spouses

Santiago Vasquez and Lorenza Oruma. After both spouses died, their only son Felixberto inherited the lot. In

1975, Felixberto executed a duly notarized document entitled “Declaration of Heirship and Deed of Absolute

Sale” in favor of Cosme Pido. Since 1960, Teodoro Acap had been the tenant of a portion of the said land,

covering an area of 9,500 sq. m. When ownership was transferred in 1975 by Felixberto to Cosme Pido, Acap

continued to be the registered tenant thereof and religiously paid his leasehold rentals to Pido and thereafter,

upon Pido’s death, to his widow Laurenciana. The controversy began when Pido died interstate and on 27

November 1981, his surviving heirs executed a notarized document denominated as “Declaration of Heirship

and Waiver of Rights of Lot 1130 Hinigaran Cadastre,” wherein they declared to have adjudicated upon

themselves the parcel of land in equal share, and that they waive, quitclaim all right, interests and

participation over the parcel of land in favor of Edy de los Reyes. The document was signed by all of Pido’s

heirs. Edy de los Reyes did not sign said document. It will be noted that at the time of Cosme Pido’s death,

title to the property continued to be registered in the name of the Vasquez spouses. Upon obtaining the

Declaration of Heirship with Waiver of Rights in his favor, de los Reyes filed the same with the Registry of

Deeds as part of a notice of an adverse claim against the original certificate of title.

Thereafter, delos Reyes sought for Acap to personally inform him that he had become the new owner of the

land and that the lease rentals thereon should be paid to him. Delos Reyes alleged that he and Acap entered

into an oral lease agreement wherein Acap agreed to pay 10 cavans of palay per annum as lease rental. In

1982, Acap allegedly complied with said obligation. In 1983, however, Acap refused to pay any further lease

rentals on the land, prompting delos Reyes to seek the assistance of the then Ministry of Agrarian Reform

(MAR) in Hinigaran, Negros Occidental. The MAR invited Acap, who sent his wife, to a conference

scheduled on 13 October 1983. The wife stated that the she and her husband did not recognize delos Reyes’s

claim of ownership over the land. On 28 April 1988, after the lapse of four (4) years, delos Reys field a

complaint for recovery of possession and damages against Acap, alleging that as his leasehold tenant, Acap

refused and failed to pay the agreed annual rental of 10 cavans of palay despite repeated demands. On 20

August 1991, the lower court rendered a decision in favor of delos Reyes, ordering the forfeiture of Acap’s

preferred right of a Certificae of Land Transfer under PD 27 and his farmholdings, the return of the farmland

in Acap’s possession to delos Reyes, and Acap to pay P5,000.00 as attorney’s fees, the sum of P1,000.00 as

expenses of litigation and the amount of P10,000.00 as actual damages.

Aggrieved, petitioner appealed to the Court of Appeals. Subsequently, the CA affirmed the lower court’s

decision, holding that de los Reyes had acquired ownership of Lot No. 1130 of the Cadastral Survey of

Hinigaran, Negros Occidental based on a document entitled “Declaration of Heirship and Waiver of Rights”,

and ordering the dispossession of Acap as leasehold tenant of the land for failure to pay rentals. Hence, the

petition for review on certiorari.

The Supreme Court granted the petition, set aside the decision of the RTC Negros Occidental, dismissed the

complaint for recovery of possession and damages against Acap for failure to properly state a cause of action,

without prejudice to private respondent taking the proper legal steps to establish the legal mode by which he

claims to have acquired ownership of the land in question.

1.

Asserted right or claim to ownership not sufficient per se to give rise to ownership over the res

An asserted right or claim to ownership or a real right over a thing arising from a juridical act,

however justified, is not per se sufficient to give rise to ownership over the res. That right or title must be

Sales, 2003 ( 1 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

completed by fulfilling certain conditions imposed by law. Hence, ownership and real rights are acquired only

pursuant to a legal mode or process. While title is the juridical justification, mode is the actual process of

acquisition transfer of ownership over a thing in question.

2.

Classes of modes of acquiring ownership

Under Article 712 of the Civil Code, the modes of acquiring ownership are generally classified into

two (2) classes, namely, the original mode (i.e, through occupation, acquisitive prescription, law or

intellectual creation) and the derivative mode (i.e., through succession mortis causa or tradition as a result of

certain contracts, such as sale, barter, donation, assignment or mutuum).

3.

Contract of Sale; “Declaration of Heirship and Waiver of Rights” an extrajudicial settlement

between heirs under Rule 74 of the Rules of Court

In a Contract of Sale, one of the contracting parties obligates himself to transfer the ownership of and

to deliver a determinate thing, and the other party to pay a price certain in money or its equivalent. On the

other hand, a declaration of heirship and waiver of rights operates as a public instrument when filed with the

Registry of Deeds whereby the intestate heirs adjudicate and divide the estate left by the decedent among

themselves as they see fit. It is in effect an extrajudicial settlement between the heirs under Rule 74 of the

Rules of Court. In the present case, the trial court erred in equating the nature and effect of the Declaration of

Heirship and Waiver of Rights the same with a contract (deed) of sale.

4.

Sale of hereditary rights and waiver of hereditary rights distinguished

There is a marked difference between a sale of hereditary rights and a waiver of hereditary rights. The

first presumes the existence of a contract or deed of sale between the parties. The second is, technically

speaking, a mode of extinction of ownership where there is an abdication or intentional relinquishment of a

known right with knowledge of its existence and intention to relinquish it, in favor of other persons who are

co-heirs in the succession. In the present case, de los Reyes, being then a stranger to the succession of Cosme

Pido, cannot conclusively claim ownership over the subject lot on the sole basis of the waiver document

which neither recites the elements of either a sale, or a donation, or any other derivative mode of acquiring

ownership.

5.

sale

Summon of Ministry of Agrarian Reform does not conclude actuality of sale nor notice of such

The conclusion, made by the trial and appellate courts, that a “sale” transpired between Cosme Pido’s

heirs and de los Reyes and that Acap acquired actual knowledge of said sale when he was summoned by the

Ministry of Agrarian Reform to discuss de los Reyes’ claim over the lot in question, has no basis both in fact

and in law.

6.

A notice of adverse claim does not prove ownership over the lot; Adverse claim not sufficient to

cancel the certificate of tile and for another to be issued in his name

A notice of adverse claim, by its nature, does not however prove private respondent’s ownership over

the tenanted lot. “A notice of adverse claim is nothing but a notice of a claim adverse to the registered owner,

the validity of which is yet to be established in court at some future date, and is no better than a notice of lis

pendens which is a notice of a case already pending in court.” In the present case, while the existence of said

adverse claim was duly proven (thus being filed with the Registry of Deeds which contained the Declaration

of Heirship with Waiver of rights an was annotated at the back of the Original Certificate of Title to the land

in question), there is no evidence whatsoever that a deed of sale was executed between Cosme Pido’s heirs

and de los Reyes transferring the rights of the heirs to the land in favor of de los Reyes. De los Reyes’ right or

interest therefore in the tenanted lot remains an adverse claim which cannot by itself be sufficient to cancel

the OCT to the land and title to be issued in de los Reyes’ name.

7.

Transaction between heirs and de los Reyes binding between parties, but cannot affect right of

Sales, 2003 ( 2 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

Acap to tenanted land without corresponding proof thereof

While the transaction between Pido’s heirs and de los Reyes may be binding on both parties, the right

of Acap as a registered tenant to the land cannot be perfunctorily forfeited on a mere allegation of de los

Reyes’ ownership without the corresponding proof thereof. Acap had been a registered tenant in the subject

land since 1960 and religiously paid lease rentals thereon. In his mind, he continued to be the registered tenant

of Cosme Pido and his family (after Pido’s death), even if in 1982, de los Reyes allegedly informed Acap that

he had become the new owner of the land.

8.

No unjustified or deliberate refusal to pay the lease rentals to the landowner / agricultural

lessor

De los Reyes never registered the Declaration of Heirship with Waiver of Rights with the Registry of

Deeds or with the MAR, but instead, he filed a notice of adverse claim on the said lot to establish ownership

thereof (which cannot be done). It stands to reason, therefore, to hold that there was no unjustified or

deliberate refusal by Acap to pay the lease rentals or amortizations to the landowner/agricultural lessor which,

in this case, de los Reyes failed to established in his favor by clear and convincing evidence. This

notwithstanding the fact that initially, Acap may have, in good faith, assumed such statement of de los Reyes

to be true and may have in fact delivered 10 cavans of palay as annual rental for 1982 to latter. For in 1983, it

is clear that Acap had misgivings over de los Reyes’ claim of ownership over the said land because in the

October 1983 MAR conference, his wife Laurenciana categorically denied all of de los Reyes’ allegations. In

fact, Acap even secured a certificate from the MAR dated 9 May 1988 to the effect that he continued to be the

registered tenant of Cosme Pido and not of delos Reyes.

9.

Sanction of forfeiture of tenant’s preferred right and possession of farmholdings should not be

applied

The sanction of forfeiture of his preferred right to be issued a Certificate of Land Transfer under PD

27 and to the possession of his farmholdings should not be applied against Acap, since de los Reyes has not

established a cause of action for recovery of possession against Acap.

[2]

Adalin vs. CA [G.R. No. 120191. October 10, 1997.]

First Division, Hermosisima Jr. (J): 3 concurring, 1 took no part

Facts: In August 1987, Elena K. Palanca, in behalf of the Kado siblings, commissioned Ester Bautista to look

for buyers for their property fronting the Imperial Hotel in Cotabato City. Bautista logically offered said

property to the owners of the Imperial Hotel which may be expected to grab the offer and take advantage of

the proximity of the property to the hotel site. True enough, Faustino Yu, the President-General Manager of

Imperial Hotel, agreed to buy said property. Thus during that same month of August 1987, a conference was

held in Yu’s office at the Imperial Hotel. Present there were Yu, Loreto Adalin who was one of the tenants of

the 5-door, 1-storey building standing on the subject property, and Elena Palanca and Teofilo Kado in their

own behalf as sellers and in behalf of the other tenants of said building. During the conference, Yu and Lim

categorically asked Palanca whether the other tenants were interested to buy the property, but Palanca also

categorically answered that the other tenants were not interested to buy the same. Consequently, they agreed

to meet at the house of Palanca on 2 September 1987 to finalize the sale. On said date, Loreto Adalin; Yu and

Lim and their legal counsel; Palanca and Kado and their legal counsel; and one other tenant, Magno Adalin,

met at Palanca’s house. Magno Adalin was there in his own behalf as tenant of two of the five doors of the

one-storey building standing on the subject property and in behalf of the tenants of the two other doors,

namely. Carlos Calingasan and Demetrio Adaya. Again, Yu and Lim asked Palanca and Magno Adalin

whether the other tenants were interested to buy the subject property, and Magno Adalin unequivocally

answered that he and the other tenants were not so interested mainly because they could not afford it.

However, Magno Adalin asserted that he and the other tenants were each entitled to a disturbance fee of

Sales, 2003 ( 3 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

P50,000.00 as consideration for their vacating the subject property. During said meeting, Palanca and Kado,

as sellers, and Loreto Adalin and Yu and Lim, as buyers, agreed that the latter will pay P300,000 as

downpayment for the property and that as soon as the former secures the eviction of the tenants, they will be

paid the balance of P2,300,000. Pursuant to the above terms and conditions, a Deed of Conditional Sale was

drafted by the counsel of Yu and Lim. On 8 September 1987, at Yu’s Imperial Hotel office, Palanca and

Eduarda Vargas, representing the sellers, and Loreto Adalin and Yu and Lim signed the Deed of Conditional

Sale. They also agreed to defer the registration of the deed until after the sellers have secured the eviction of

the tenants from the subject property. The tenants, however, refused to vacate the subject property.

Being under obligation to secure the eviction of the tenants, in accordance with the terms and conditions of

the Deed of Conditional Sale, Elena Palanca filed with the Barangay Captain a letter complaint for unlawful

detainer against the said tenants. Two days after Palanca filed an ejectment case before the Barangay Captain

against the tenants of the subject property, Magno Adalin, Demetrio Adaya and Carlos Calingasan wrote

letters to Palanca informing the Kado siblings that they have decided to purchase the doors that they were

leasing for the purchase price of P600,000 per door. Almost instantly, Palanca, in behalf of the Kado siblings,

accepted the offer of the said tenants and returned the downpayments of Yu and Lim. Of course, the latter

refused to accept the reimbursements.

Yu and Lim filed a complaint witht the Barangay Captain for Breach of Contract against Elena Palanca.

During the conference, Yu and Lim, if only to accommodate Magno Adalin and settle the case amicably,

agreed to buy only 1 door each so that the latter could purchase the two doors he was occupying. However,

Magno Adalin adamantly refused, claiming that he was already the owner of the 2 doors. When Lim asked

Magno Adalin to show the Deed of Sale for the two doors, the latter insouciantly walked out. There being no

settlement forged, on 16 May 1988, the Barangay Captain issued the Certification to File Action.

On 5 May 1988, Yu and Lim filed their complaint for ‘Specific Performance’ against the Palanca, et. al. and

Adalin in the RTC. On 14 June 1988, Yu and Lim caused the annotation of a “Notice of Lis Pendens” at the

dorsal portion of TCT 12963. On 25 October 1988, Calingasan, Adalin, et.al. filed a ‘Motion for Intervention

as Plaintiffs-Intervenors’ appending thereto a copy of the ‘Deed of Sale of Registered Land’ signed by

Palanca, et.al. On 27 October 1988, Calingasan et.al. filed the “Deed of Sale of Registered Land” with the

Register of Deeds on the basis of which TCT 24791 over the property was issued under their names. On the

same day, Calingasan, et.al. filed in the Court a quo a “Motion To Admit Complaint-In-Intervention”.

Attached to the Complaint-In-Intervention was the “Deed of Sale of Registered Land.” Yu and Lim were

shocked to learn that Palanca, et. al. had signed the said deed. As a counter-move, Yu and Lim filed a motion

for leave to amend Complaint and, on 11November1988, filed their Amended Complaint impleading

Calingasan, et. al. as additional Defendants. Palanca, et.al. suffered a rebuff when, on 10 January 1989, the

RTC General Santos City issued an Order dismissing the Petition of Calingasan, et. al. for consignation. In the

meantime, on 30 November 1989, Loreto Adalin died and was substituted, per order of the Court a quo, on 5

January 1990, by his heirs, namely, Anita, Anelita, Loreto, Jr., Teresita, Wilfredo, Lilibeth, Nelson, Helen and

Jocel, all surnamed Adalin. After trial, the Court a quo rendered judgment in favor of Calingasan, Adalin,

et.al. The Court order Palanca, et.al. in solidum to pay moral damages of P500,000.00, P100,000.00

exemplary damages each to both Yu and Lim and P50,000.00 as and for attorney’s fees. They were ordered to

return the P200,000.00 initial payment received by them with legal interest from date of receipt thereof up to

3 November 1987.

Yu and Lim wasted no time in appealing from the decision of the trial court. They were vindicated when the

Court of Appeals rendered its decision in their favor. Accordingly, the Court of Appeals rendered another

judgment in the case and ordered that the “Deed of Conditional Sale” was declared valid; that the “Deeds of

Sale of Registered Land” and TCT 24791 were hereby declared null and void; that Calingasan, et.al. except

the heirs of Loreto Adalin were ordered to vacate the property within 30 days from the finality of the

Decision; that Palanca, et.al were ordered to execute, in favor of Yu and Lim, a “Deed of Absolute Sale”

Sales, 2003 ( 4 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

covering 4 doors of the property (which includes the area of the property on which said four doors were

constructed) except the door purchased by Loreto Adalin, free of any liens or encumbrances; that Yu amd Lim

were ordered to remit to Palanca, et.al. the balance of the purchase price of the 4 doors in the amount of

P1,880,000; that Palanca, et.al. were ordered to refund to Calingasan, et.al. the amount of P840,000 which

they paid for the property under the “Deed of Conditional Sale of Registered Land” without interest

considering that they also acted in bad faith; that Magno Adalin was ordered to pay the amount of P3,000 a

month, and each of other tenants, except Loreto Adalin, the amount of P1,500 to Yu and Lim, from November

1987, up to the time the property was vacated and delivered to the latter, as reasonable compensation for the

occupancy of the property, with interest thereon at the rate of 6% per annum; and that Palanca, et.al. were

ordered to pay, jointly and severally, to Yu and Lim, individually, the amount of P100,000.00 by way of moral

damages, P20,000.00 by way of exemplary damages and P20,000.00 by way of attorney’s fees. Hence, the

petition for review.

The Supreme Court dismissed the petition; with costs against Calingasan, Adalin, et.al.

1.

Grounds merely splits aspects of the issue, i.e. the true nature of transaction entered by Yu and

Lim with the Kado siblings

The grounds relied upon by Calingasan, Adalin, et.al. are essentially a splitting of the various aspects

of the one pivotal issue that holds the key to the resolution of this controversy: the true nature of the sale

transaction entered into by the Kado siblings with Faustino Yu and Antonio Lim. The Courts task amounts to

a declaration of what kind of contract had been entered into by said parties and of what their respective rights

and obligations are thereunder.

2.

Deed of Conditional Sale; Obligation of the seller to eject the tenants and the obligation of the

buyer to pay the balance of the purchase price; Choice as to whom to sell is determined

Palanca, in behalf of the Kado siblings who had already committed to sell the property to Yu and Lim

and Loreto Adalin, understood her obligation to eject the tenants on the subject property. Having gone to the

extent of filing an ejectment case before the Barangay Captain, Palanca clearly showed an intelligent

appreciation of the nature of the transaction that she had entered into: that she, in behalf of the Kado siblings,

had already sold the subject property to Yu and Lim and Loreto Adalin, and that only the payment of the

balance of the purchase price was subject to the condition that she would successfully secure the eviction of

their tenants. In the sense that the payment of the balance of the purchase price was subject to a condition, the

sale transaction was not yet completed, and both sellers and buyers have their respective obligations yet to be

fulfilled: the former, the ejectment of their tenants; and the latter, the payment of the balance of the purchase

price. In this sense, the Deed of Conditional Sale may be an accurate denomination of the transaction. But the

sale was conditional only inasmuch as there remained yet to be fulfilled, the obligation of the sellers to eject

their tenants and the obligation of the buyers to pay the balance of the purchase price. The choice of who to

sell the property to, however, had already been made by the sellers and is thus no longer subject to any

condition nor open to any change. In that sense, therefore, the sale made by Palanca to Yu, Lim, and Adalin

was definitive and absolute.

3.

No acts of parties justifies radical change of Palanca’s posture; No legal basis for the acceptance

of tenant’s offer to buy

Nothing in the acts of the sellers and buyers before, during or after the said transaction justifies the

radical change of posture of Palanca who, in order to provide a legal basis for her later acceptance of the

tenants’ offer to buy the same property, in effect claimed that the sale, being conditional, was dependent on

the sellers not changing their minds about selling the property to Yu and Lim. The tenants, for their part,

defended Palanca’s subsequent dealing with them by asserting their option rights under Palanca’s letter of 2

September 1987 and harking on the non-fulfillment of the condition that their ejectment be secured first.

4.

No legal rationalizing can sanction Palanca’s arbitrary breach of contract

Sales, 2003 ( 5 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

The Court cannot countenance the double dealing perpetrated by Palanca in behalf of the Kado

siblings. No amount of legal rationalizing can sanction the arbitrary breach of contract that Palanca committed

in accepting the offer of Magno Adalin, Adaya and Calingasan to purchase a property already earlier sold to

Yu and Lim.

5.

Alleged 30-day option for tenant to purchase void for lack of consideration

The 30-day option to purchase the subject property allegedly given to the tenants as contained in the 2

September 1987 letter of Palanca, is not valid for utter lack of consideration.

6.

Palanca and tenants estopped

Yu and Lim twice asked Palanca and the tenants concerned as to whether or not the latter were

interested to buy the subject property, and twice, too, the answer given was that the said tenants were not

interested to buy the subject property because they could not afford it. Clearly, said tenants and Palanca, who

represented the former in the initial negotiations with Yu and Lim, are estopped from denying their earlier

statement to the effect that the said tenants Magno Adalin, Adaya and Calingasan had no intention of buying

the four doors that they were leasing from the Kado siblings.

7.

Subsequent sale clearly made in bad faith

The subsequent sale of the subject property by Palanca to the tenants, smacks of gross bad faith,

considering that Palanca and the said tenants were in full awareness of the August and September negotiations

between Bautista and Palanca, on the one hand, and Loreto Adalin, Faustino Yu and Antonio Lim, on the

other, for the sale of the one-storey building. It cannot be denied, thus, that Palanca and the said tenants

entered into the subsequent or second sale notwithstanding their full knowledge of the subsistence of the

earlier sale over the same property to Yu and Lim.

8.

Prior registration cannot erase gross bad faith characterizing second sale

Though the second sale to the said tenants was registered, such prior registration cannot erase the

gross bad faith that characterized such second sale, and consequently, there is no legal basis to rule that such

second sale prevails over the first sale of the said property to Yu and Lim.

9.

Refusal of tenants from vacating property not a valid justification to renege on obligation to sell

Palanca, et.al. cannot invoke the refusal of the tenants to vacate the property and the latter’s decision

to themselves purchase the property as a valid justification to renege on and turn their backs against their

obligation to deliver or cause the eviction of the tenants from and deliver physical possession o the property to

Yu and Lim. It would be the zenith of inequity for Palanca, et. al. to invoke the occupation by the tenants, as

of the property, as a justification to ignore their obligation to have the tenants evicted from the property and

for them to give P50,000.00 disturbance fee for each of the tenants and a justification for the latter to hold on

to the possession of the property.

10.

Second sale cannot be preferred even if the prior conditional sale was not consummated

Assuming, gratia arguendi, for the nonce, that there had been no consummation of the “Deed of

Conditional Sale” by reason of the non-delivery to Yu and Lim of the property, it does not thereby mean that

the “Deed of Sale of Registered Land” executed by Palanca, et.al and the tenants should be given preference.

[3]

Addison vs. Felix [G.R. No. 12342. August 3, 1918.]

En Banc, Fisher (J): 5 concurring

Facts: By a public instrument dated 11 June 1914, A. A. Addison sold to Marciana Felix, with the consent of

her husband, Balbino Tioco, 4 parcels of land. Felix paid, at the time of the execution of the deed, the sum of

Sales, 2003 ( 6 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

P3,000 on account of the purchase price, and bound herself to pay the remainder in installments, the first of

P2,000 on 15 July 1914, the second of P5,000 30 days after the issuance to her of a certificate of title under

the Land Registration Act, and further, within 10 years from the date of such title, P10 for each coconut tree in

bearing and P5 for each such tree not in bearing, that might be growing on said 4 parcels of land on the date

of the issuance of title to her, with the condition that the total price should not exceed P85,000. It was further

stipulated that the purchaser was to deliver to the vendor 25% of the value of the products that she might

obtain from the 4 parcels from the moment she takes possession of them until the Torrens certificate of title be

issued in her favor. It was also covenanted that within 1 year from the date of the certificate of title in favor of

Marciana Felix, this latter may rescind the present contract of purchase and sale, in which case Felix shall be

obliged to return to Addison the net value of all the products of the 4 parcels sold, and shall be obliged to

return to her all the sums that was paid, together with interest at the rate of 10% per annum. After the

execution of the deed of sale, at the request of Felix. Addison went to Lucena, accompanied by the former’s

representative, for the purpose of designating and delivering the lands sold. He was able to designate only 2 of

the 4 parcels, and more than 2/3s of these were found to be in the possession of one Juan Villafuerte, who

claimed to be the owner of the parts so occupied by him. Addison admitted that Felix would have to bring suit

to obtain possession of the land. In June 1914, Felix filed an application with the Land Court for the

registration in her name of 4 parcels of land described in the deed of sale executed in her favor, to obtain from

the Land Court a writ of injunction against the occupants, and for the purpose of the issuance of this writ. The

proceedings in the matter of this application were subsequently dismissed, for failure to present the required

plans within the period of the time allowed for the purpose.

In January 1915, Addison filed suit in the CFI Manila to compel Felix to make payment of the first

installment of P2,000, demandable on 15 July 1914, and of the interest in arrears, at the stipulated rate of 8%

per annum. Felix and Tioco answered the complaint and alleged by way of special defense that Addison had

absolutely failed to deliver the lands that were the subject matter of the sale, notwithstanding the demands

made upon him for this purpose. She therefore asked that she be absolved from the complaint, and that, after a

declaration of the rescission of the contract of the purchase and sale of said lands, Addison be ordered to

refund the P3,000 that had been paid to him on account, together with the interest agreed upon, and to pay an

indemnity for the losses and damages which the defendant alleged she had suffered through Addison’s

nonfulfilment of the contract. The trial court rendered judgment in favor of Felix, holding the contract of sale

to be rescinded and ordering the return the P3,000 paid on account of the price, together with interest thereon

at the rate of 10% per annum. From this judgment Addison appealed.

The Supreme Court held that the contract of purchase and sale entered into by and between the Parties on 11

June 1914 is rescinded, and ordered Addison to make restitution of the sum of P3,000 received by him on

account of the price of the sale, together with interest thereon at the legal rate of 6% per annum from the date

of the filing of the complaint until payment, with the costs of both instances against Addison.

1.

sold

Cross Complaint not founded on conventional rescission but on the failure to deliver the land

The Cross complaint is not founded on the hypothesis of the conventional rescission relied upon by

the court, but on the failure to deliver the land sold. The right to rescind the contract by virtue of the special

agreement not only did not exist from the moment of the execution of the contract up to one year after the

registration of the land, but does not accrue until the land is registered. The wording of the clause

substantiates the contention. The one year’s deliberation granted to the purchaser was to be counted “from the

date of the certificate of title . . ..” Therefore the right to elect to rescind the contract was subject to a

condition, namely, the issuance of the title. The record shows that up to the present time that condition has not

been fulfilled; consequently Felix cannot be heard to invoke a right which depends on the existence of that

condition.

2.

“Fulfillment of condition impossible for reason imputable to party” not presented

Sales, 2003 ( 7 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

If in-the cross-complaint it had been alleged that the fulfillment of the condition was impossible for

reasons imputable to Addison, and if this allegation had been proven, perhaps the condition would have been

considered as fulfilled (arts. 1117, 1118, and 1119, Civ. Code). This issue, however, was not presented in

Felix’s answer.

3.

Tradition / Delivery by the vendor of the thing sold

The Code imposes upon the vendor the obligation to deliver the thing sold. The thing is considered to

be delivered when it is placed “in the hands and possession of the vendee.” (Civ. Code, art. 1462.) It is true

that the same article declares that the execution of a public instrument is equivalent to the delivery of the

thing which is the object of the contract, but, in order that this symbolic delivery may produce the effect of

tradition, it is necessary that the vendor shall have had such control over the thing sold that, at the moment of

the sale, its material delivery could have been made. It is not enough to confer upon the purchaser the

ownership and the right of possession. The thing sold must be placed in his control. When there is no

impediment whatever to prevent the thing sold passing into the tenancy of the purchaser by the sole will of

the vendor, symbolic delivery through the execution of a public instrument is sufficient. But if,

notwithstanding the execution of the instrument, the purchaser cannot have the enjoyment and material

tenancy of the thing and make use of it himself or through another in his name, because such tenancy and

enjoyment are opposed by the interposition of another will, then fiction yields to reality — the delivery has

not been effected.

4.

Delivery, according to Dalloz

The word ‘delivery’ expresses a complex idea, the abandonment of the thing by the person who

makes the delivery and the taking control of it by the person to whom the delivery is made (Dalloz;Gen. Rep.,

vol. 43, p. 174 in his commentaries on article 1604 of the French Civil Code).

5.

Execution of a public instrument, when sufficient

The execution of a public instrument is sufficient for the purposes of the abandonment made by the

vendor, but it is not always sufficient to permit of the apprehension of the thing by the purchaser.

6.

Fictitious tradition not necessarily implies real tradition of the thing sold

When the sale is made through the means of a public instrument, the execution of this latter is

equivalent to the delivery of the thing sold: which does not and cannot mean that this fictitious tradition

necessarily implies the real tradition of the thing sold, for it is incontrovertible that, while its ownership still

pertains to the vendor (and with greater reason if it does not), a third person may be in possession of the same

thing; wherefore, though, as a general rule, he who purchases by means of a public instrument should be

deemed to be the possessor in fact, yet this presumption gives way before proof to the contrary (Supreme

court of Spain, decision of November 10, 1903, [Civ. Rep., vol. 96, p. 560] interpreting article 1462 of the

Civil Code).

7.

Rescission of sale and return of price due to non-delivery of thing sold

In the present case, the mere execution of the instrument was not a fulfillment of the vendor’s

obligation to deliver the thing sold, and that from such nonfulfillment arises the purchaser’s right to demand,

as she has demanded, the rescission of the sale and the return of the price. (Civ. Code, arts. 1506 and 1124.)

8.

No agreement for vendee to take steps to obtain material possession of thing sold

If the sale had been made under the express agreement of imposing upon the purchaser the obligation

to take the necessary steps to obtain the material possession of the thing sold, and it were proven that she

knew that the thing was in the possession of a third person claiming to have property rights therein, such

agreement would be perfectly valid. But there is nothing in the instrument which would indicate, even

implicitly, that such was the agreement.

Sales, 2003 ( 8 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

8.

Possession while land is being registered contemplated in contract

The obligation was incumbent upon Felix to apply for and obtain the registration of the land in the

new registry of property; but from this it cannot be concluded that she had to await the final decision of the

Court of Land Registration, in order to be able to enjoy the property sold. On the contrary, it was expressly

stipulated in the contract that the purchaser should deliver to the vendor 1/4 “of the products of the 4 parcels

from the moment when she takes possession of them until the Torrens certificate of title be issued in her

favor.” This obviously shows that it was not foreseen that the purchaser might be deprived of her possession

during the course of the registration proceedings, but that the transaction rested on the assumption that she

was to have, during said period, the material possession and enjoyment of the 4 parcels of land.

9.

Legal interest due as rescission is made by virtue of provisions of law

As the rescission is made by virtue of the provisions of law and not by contractual agreement, it is not

the conventional but the legal interest that is demandable.

[4]

Adelfa Properties vs. CA [G.R. No. 111238. January 25, 1995.]

Second Division, Regalado (J): 3 concurring

Facts: Rosario Jimenez-Castaneda, Salud Jimenez and their brothers, Jose and Dominador Jimenez, were the

registered co-owners of a parcel of land consisting of 17,710 sq. ms (TCT 309773) situated in Barrio Culasi,

Las Piñas, Metro Manila. On 28 July 1988, Jose and Dominador Jimenez sold their share consisting of 1/2 of

said parcel of land, specifically the eastern portion thereof, to Adelfa Properties pursuant to a “Kasulatan sa

Bilihan ng Lupa.” Subsequently, a “Confirmatory Extrajudicial Partition Agreement” was executed by the

Jimenezes, wherein the eastern portion of the subject lot, with an area of 8,855 sq. ms. was adjudicated to Jose

and Dominador Jimenez, while the western portion was allocated to Rosario and Salud Jimenez. Thereafter,

Adelfa Properties expressed interest in buying the western portion of the property from Rosario and Salud.

Accordingly, on 25 November 1989, an “Exclusive Option to Purchase” was executed between the parties,

with the condition that the selling price shall be P2,856,150, that the option money of P50,000 shall be

credited as partial payment upon the consummation of sale, that the balance is to be paid on or before 30

November 1989, and that in case of default by Adelfa Properties to pay the balance, the option is cancelled

and 50% of the option money shall be forfeited and the other 50% refunded upon the sale of the property to a

third party, and that all expenses including capital gains tax, cost of documentary stamps are for the account

of the vendors and the expenses for the registration of the deed of sale for the account of Adelfa properties.

Considering, however, that the owner’s copy of the certificate of title issued to Salud Jimenez had been lost, a

petition for the re-issuance of a new owner’s copy of said certificate of title was filed in court through Atty.

Bayani L. Bernardo. Eventually, a new owner’s copy of the certificate of title was issued but it remained in

the possession of Atty. Bernardo until he turned it over to Adelfa Properties, Inc.

Before Adelfa Properties could make payment, it received summons on 29 November 1989, together with a

copy of a complaint filed by the nephews and nieces of Rosario and Salud against the latter, Jose and

Dominador Jimenez, and Adelfa Properties in the RTC Makati (Civil Case 89-5541), for annulment of the

deed of sale in favor of Household Corporation and recovery of ownership of the property covered by TCT

309773. As a consequence, in a letter dated 29 November 1989, Adelfa Properties informed Rosario and

Salud that it would hold payment of the full purchase price and suggested that the latter settle the case with

their nephews and nieces, adding that “if possible, although 30 November 1989 is a holiday, we will be

waiting for you and said plaintiffs at our office up to 7:00 p.m.” Another letter of the same tenor and of even

date was sent by Adelfa Properties to Jose and Dominador Jimenez. Salud Jimenez refused to heed the

suggestion of Adelfa Properties and attributed the suspension of payment of the purchase price to “lack of

word of honor.” On 7 December 1989, Adelfa Properties caused to be annotated on the title of the lot its

option contract with Salud and Rosario, and its contract of sale with Jose and Dominador Jimenez, as Entry

Sales, 2003 ( 9 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

No. 1437-4 and entry No. 1438-4, respectively. On 14 December 1989, Rosario and Salud sent Francisca

Jimenez to see Atty. Bernardo, in his capacity as Adelfa Properties’ counsel, and to inform the latter that they

were cancelling the transaction. In turn, Atty. Bernardo offered to pay the purchase price provided that

P500,000.00 be deducted therefrom for the settlement of the civil case. This was rejected by Rosario and

Salud. On 22 December 1989, Atty. Bernardo wrote Rosario and Salud on the same matter but this time

reducing the amount from P500,000.00 to P300,000.00, and this was also rejected by the latter. On 23

February 1990, the RTC dismissed Civil Case 89-5541.

On 28 February 1990, Adelfa Properties caused to be annotated anew on TCT 309773 the exclusive option to

purchase as Entry 4442-4.On the same day, 28 February 1990, Rosario and Salud executed a Deed of

Conditional Sale in favor of Emylene Chua over the same parcel of land for P3,029,250.00, of which

P1,500,000.00 was paid to the former on said date, with the balance to be paid upon the transfer of title to the

specified 1/2 portion. On 16 April 1990, Atty. Bernardo wrote Rosario and Salud informing the latter that in

view of the dismissal of the case against them, Adelfa Properties was willing to pay the purchase price, and he

requested that the corresponding deed of absolute sale be executed. This was ignored by Rosario and Salud.

On 27 July 1990, Jimenez’ counsel sent a letter to Adelfa Properties enclosing therein a check for P25,000.00

representing the refund of 50% of the option money paid under the exclusive option to purchase. Rosario and

Salud then requested Adelfa Properties to return the owner’s duplicate copy of the certificate of title of Salud

Jimenez. Adelfa Properties failed to surrender the certificate of title.

Rosario and Salud Jimenez filed Civil Case 7532 in the RTC Pasay City (Branch 113) for annulment of

contract with damages, praying, among others, that the exclusive option to purchase be declared null and

void; that Adelfa Properties be ordered to return the owner’s duplicate certificate of title; and that the

annotation of the option contract on TCT 309773 be cancelled. Emylene Chua, the subsequent purchaser of

the lot, filed a complaint in intervention. On 5 September 1991, the trial court rendered judgment holding that

the agreement entered into by the parties was merely an option contract, and declaring that the suspension of

payment by Adelfa Properties constituted a counter-offer which, therefore, was tantamount to a rejection of

the option. It likewise ruled that Adelfa Properties could not validly suspend payment in favor of Rosario and

Salud on the ground that the vindicatory action filed by the latter’s kin did not involve the western portion of

the land covered by the contract between the parties, but the eastern portion thereof which was the subject of

the sale between Adelfa Properties and the brothers Jose and Dominador Jimenez. The trial court then directed

the cancellation of the exclusive option to purchase, declared the sale to intervenor Emylene Chua as valid

and binding, and ordered Adelfa Properties to pay damages and attorney’s fees to Rosario and Salud, with

costs.

On appeal, the Court of appeals affirmed in toto the decision of the court a quo (CA-GR 34767) and held that

the failure of petitioner to pay the purchase price within the period agreed upon was tantamount to an election

by petitioner not to buy the property; that the suspension of payment constituted an imposition of a condition

which was actually a counter-offer amounting to a rejection of the option; and that Article 1590 of the Civil

Code on suspension of payments applies only to a contract of sale or a contract to sell, but not to an option

contract which it opined was the nature of the document subject of the case at bar. Said appellate court

similarly upheld the validity of the deed of conditional sale executed by Rosario and Salud in favor of

intervenor Emylene Chua. Hence, the petition for review on certiorari.

The Supreme Court affirmed the assailed judgment of the Court of Appeals in CA-GR CV 34767, with

modificatory premises.

1.

Agreement between parties a contract to sell and not an option contract or a contract of sale

The alleged option contract is a contract to sell, rather than a contract of sale. The distinction between

the two is important for in contract of sale, the title passes to the vendee upon the delivery of the thing sold;

whereas in a contract to sell, by agreement the ownership is reserved in the vendor and is not to pass until the

Sales, 2003 ( 10 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

full payment of the price. In a contract of sale, the vendor has lost and cannot recover ownership until and

unless the contract is resolved or rescinded; whereas in a contract to sell, title is retained by the vendor until

the full payment of the price, such payment being a positive suspensive condition and failure of which is not a

breach but an event that prevents the obligation of the vendor to convey title from becoming effective. Thus, a

deed of sale is considered absolute in nature where there is neither a stipulation in the deed that title to the

property sold is reserved in the seller until the full payment of the price, nor one giving the vendor the right to

unilaterally resolve the contract the moment the buyer fails to pay within a fixed period.

2.

Intent not to transfer ownership need not be expressed

The parties never intended to transfer ownership to Adelfa Properties to completion of payment of the

purchase price, this is inferred by the fact that the exclusive option to purchase, although it provided for

automatic rescission of the contract and partial forfeiture of the amount already paid in case of default, does

not mention that Adelfa Properties is obliged to return possession or ownership of the property as a

consequence of non-payment. There is no stipulation anent reversion or reconveyance of the property in the

event that petitioner does not comply with its obligation. With the absence of such a stipulation, it may legally

be inferred that there was an implied agreement that ownership shall not pass to the purchaser until he had

fully paid the price. Article 1478 of the Civil Code does not require that such a stipulation be expressly made.

Consequently, an implied stipulation to that effect is considered valid and binding and enforceable between

the parties. A contract which contains this kind of stipulation is considered a contract to sell. Moreover, that

the parties really intended to execute a contract to sell is bolstered by the fact that the deed of absolute sale

would have been issued only upon the payment of the balance of the purchase price, as may be gleaned from

Adelfa Properties’ letter dated 16 April 1990 wherein it informed the vendors that it “is now ready and willing

to pay you simultaneously with the execution of the corresponding deed of absolute sale.”

3.

No actual or constructive delivery of property to indicate contract of sale; Circumstances

negate presumption of possession of title is to be understood as delivery

It has not been shown that there was delivery of the property, actual or constructive, made. The

exclusive option to purchase is not contained in a public instrument the execution of which would have been

considered equivalent to delivery. Neither did Adelfa Properties take actual, physical possession of the

property at any given time. It is true that after the reconstitution of the certificate of title, it remained in the

possession of Atty. Bayani L. Bernardo, Adelfa’s counsel. Normally, under the law, such possession by the

vendee is to be understood as a delivery. However, Rosario and Salud explained that there was really no

intention on their part to deliver the title to Adelfa Properties with the purpose of transferring ownership to it.

They claim that Atty. Bernardo had possession of the title only because he was their counsel in the petition for

reconstitution. The court found no reason not to believe said explanation, aside from the fact that such

contention was never refuted or contradicted by Adelfa Properties.

4.

Perfected contract to sell

The controverted document should legally be considered as a perfected contract to sell, and not

“strictly an option contract.”

5.

Contract interpreted to ascertain intent of parties; Title not controlling if text shows otherwise

The important task in contract interpretation is always the ascertainment of the intention of the

contracting parties and that task is to be discharged by looking to the words they used to project that intention

in their contract, all the words not just a particular word or two, and words in context not words standing

alone. Moreover, judging from the subsequent acts of the parties which will hereinafter be discussed, it is

undeniable that the intention of the parties was to enter into a contract to sell. In addition, the title of a

contract does not necessarily determine its true nature. Hence, the fact that the document under discussion is

entitled “Exclusive Option to Purchase” is not controlling where the text thereof shows that it is a contract to

sell.

Sales, 2003 ( 11 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

6.

Option defined

As used in the law on sales, an option is a continuing offer or contract by which the owner stipulates

with another that the latter shall have the right to buy the property at a fixed price within a certain time, or

under, or in compliance with, certain terms and conditions, or which gives to the owner of the property the

right to sell or demand a sale. It is also sometimes called an “unaccepted offer.” An option is not of itself a

purchase, but merely secures the privilege to buy. It is not a sale of property but a sale of the right to purchase.

It is simply a contract by which the owner of property agrees with another person that he shall have the right

to buy his property at a fixed price within a certain time. He does not sell his land; he does not then agree to

sell it; but he does sell something, that is, the right or privilege to buy at the election or option of the other

party. Its distinguishing characteristic is that it imposes no binding obligation on the person holding the

option, aside from the consideration for the offer. Until acceptance, it is not, properly speaking, a contract, and

does not vest, transfer, or agree to transfer, any title to, or any interest or right in the subject matter, but is

merely a contract by which the owner of property gives the optionee the right or privilege of accepting the

offer and buying the property on certain terms.

7.

Contract defined

A contract, like a contract to sell, involves a meeting of minds between two persons whereby one

binds himself, with respect to the other, to give something or to render some service. Contracts, in general, are

perfected by mere consent, which is manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing

and the cause which are to constitute the contract. The offer must be certain and the acceptance absolute.

8.

Distinction between an option and a contract of sale

The distinction between an “option” and a contract of sale is that an option is an unaccepted offer. It

states the terms and conditions on which the owner is willing to sell his land, if the holder elects to accept

them within the time limited. If the holder does so elect, he must give notice to the other party, and the

accepted offer thereupon becomes a valid and binding contract. If an acceptance is not made within the time

fixed, the owner is no longer bound by his offer, and the option is at an end. A contract of sale, on the other

hand, fixes definitely the relative rights and obligations of both parties at the time of its execution. The offer

and the acceptance are concurrent, since the minds of the contracting parties meet in the terms of the

agreement.

9.

Acceptance; formal or informal

Except where a formal acceptance is so required, although the acceptance must be affirmatively and

clearly made and must be evidenced by some acts or conduct communicated to the offeror, it may be made

either in a formal or an informal manner, and may be shown by acts, conduct, or words of the accepting party

that clearly manifest a present intention or determination to accept the offer to buy or sell. Thus, acceptance

may be shown by the acts, conduct, or words of a party recognizing the existence of the contract of sale. In

the present case, a perusal of the contract involved, as well as the oral and documentary evidence presented by

the parties, readily shows that there is indeed a concurrence of Adelfa’s offer to buy and the Jimenezes’

acceptance thereof.

10.

Contract clear, only performance of obligations required of parties

The offer to buy a specific piece of land was definite and certain, while the acceptance thereof was

absolute and without any condition or qualification. The agreement as to the object, the price of the property,

and the terms of payment was clear and well-defined. No other significance could be given to such acts that

than that they were meant to finalize and perfect the transaction. The parties even went beyond the basic

requirements of the law by stipulating that “all expenses including the corresponding capital gains tax, cost of

documentary stamps are for the account of the vendors, and expenses for the registration of the deed of sale in

the Registry of Deeds are for the account of Adelfa Properties, Inc.” Hence, there was nothing left to be done

except the performance of the respective obligations of the parties.

Sales, 2003 ( 12 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

11.

No counter-offer

The offer of Adelfa Properties to deduct P500,000.00, (later reduced to P300,000.00) from the

purchase price for the settlement of the civil case was not a counter-offer. There already existed a perfected

contract between the parties at the time the alleged counter-offer was made. Thus, any new offer by a party

becomes binding only when it is accepted by the other. In the case of the Jimenezes, they actually refused to

concur in said offer of petitioner, by reason of which the original terms of the contract continued to be

enforceable. At any rate, the same cannot be considered a counter-offer for the simple reason that Adelfa

Properties’ sole purpose was to settle the civil case in order that it could already comply with its obligation. In

fact, it was even indicative of a desire by Adelfa Properties to immediately comply therewith, except that it

was being prevented from doing so because of the filing of the civil case which, it believed in good faith,

rendered compliance improbable at that time. In addition, no inference can be drawn from that suggestion

given by Adelfa Properties that it was totally abandoning the original contract.

12.

Test to determine contract as a “contract of sale or purchase” or mere “option”

The test in determining whether a contract is a “contract of sale or purchase” or a mere “option” is

whether or not the agreement could be specifically enforced. There is no doubt that Adelfa’s obligation to pay

the purchase price is specific, definite and certain, and consequently binding and enforceable. Had the

Jimenezes chosen to enforce the contract, they could have specifically compelled Adelfa to pay the balance of

P2,806,150.00. This is distinctly made manifest in the contract itself as an integral stipulation, compliance

with which could legally and definitely be demanded from petitioner as a consequence.

13.

Option agreement

An agreement is only an “option” when no obligation rests on the party to make any payment except

such as may be agreed on between the parties as consideration to support the option until he has made up his

mind within the time specified. An option, and not a contract to purchase, is effected by an agreement to sell

real estate for payments to be made within specified time and providing for forfeiture of money paid upon

failure to make payment, where the purchaser does not agree to purchase, to make payment, or to bind

himself in any way other than the forfeiture of the payments made. This is not a case where no right is as yet

created nor an obligation declared, as where something further remains to be done before the buyer and seller

obligate themselves.

14.

Contract not an option contract; “Balance”

While there is jurisprudence to the effect that a contract which provides that the initial payment shall

be totally forfeited in case of default in payment is to be considered as an option contract, the contract

executed between the parties is an option contract, for the reason that the parties were already contemplating

the payment of the balance of the purchase price, and were not merely quoting an agreed value for the

property. The term “balance,” connotes a remainder or something remaining from the original total sum

already agreed upon.

15.

When earnest money given in a contract of sale

Whenever earnest money is given in a contract of sale, it shall be considered as part of the price and

as proof of the perfection of the contract. It constitutes an advance payment and must, therefore, be deducted

from the total price. Also, earnest money is given by the buyer to the seller to bind the bargain.

16.

Distinctions between earnest and option money

There are clear distinctions between

earnest money and option money, viz.: (a) earnest money is part of the purchase price, while option money is

the money given as a distinct consideration for an option contract; (b) earnest money is given only where

there is already a sale, while option money applies to a sale not yet perfected; and (c) when earnest money is

given, the buyer is bound to pay the balance, while when the would-be buyer gives option money, he is not

required to buy.

Sales, 2003 ( 13 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

17.

Article 1590, New Civil Code

Article 1590 of the Civil Code provides “Should the vendee be disturbed in the possession or

ownership of the thing acquired, or should he have reasonable grounds to fear such disturbance, by a

vindicatory action or a foreclosure of mortgage, he may suspend the payment of the price until the vendor has

caused the disturbance or danger to cease, unless the latter gives security for the return of the price in a proper

case, or it has been stipulated that, notwithstanding any such contingency, the vendee shall be bound to make

the payment. A mere act of trespass shall not authorize the suspension of the payment of the price.” As the

agreement between the parties was not an option contract but a perfected contract to sell; and therefore,

Article 1590 would properly apply.

18.

Adelfa Properties justified in suspending payment of balance by reason of vindicatory action

filed against it

In Civil Case 89-5541, it is easily discernible that, although the complaint prayed for the annulment

only of the contract of sale executed between Adelfa Properties and the Jimenez brothers, the same likewise

prayed for the recovery of therein Jimenez’ share in that parcel of land specifically covered by TCT 309773.

In other words, the Jimenezes were claiming to be co-owners of the entire parcel of land described in TCT

309773, and not only of a portion thereof nor did their claim pertain exclusively to the eastern half

adjudicated to the Jimenez brothers. Therefore, Adelfa Properties was justified in suspending payment of the

balance of the purchase price by reason of the aforesaid vindicatory action filed against it. The assurance

made by the Jimenezes that Adelfa Properties did not have to worry about the case because it was pure and

simple harassment is not the kind of guaranty contemplated under the exceptive clause in Article 1590

wherein the vendor is bound to make payment even with the existence of a vindicatory action if the vendee

should give a security for the return of the price.

19.

Jimenezes may no longer be compelled to sell and deliver subject property

Be that as it may, and the validity of the suspension of payment notwithstanding, the Jimenezes may

no longer be compelled to sell and deliver the subject property to Adelfa Properties for two reasons, that is,

Adelfa’s failure to duly effect the consignation of the purchase price after the disturbance had ceased; and,

secondarily, the fact that the contract to sell had been validly rescinded by the Jimenezes.

20.

Tender and consignation required in discharge of obligation (eg. Contract to sell); Different in

cases involving exercise of right or privilege

The mere sending of a letter by the vendee expressing the intention to pay, without the accompanying

payment, is not considered a valid tender of payment. Besides, a mere tender of payment is not sufficient to

compel the Jimenezes to deliver the property and execute the deed of absolute sale. It is consignation which is

essential in order to extinguish Adelfa Properties’ obligation to pay the balance of the purchase price. The rule

is different in case of an option contract or in legal redemption or in a sale with right to repurchase, wherein

consignation is not necessary because these cases involve an exercise of a right or privilege (to buy, redeem or

repurchase) rather than the discharge of an obligation, hence tender of payment would be sufficient to

preserve the right or privilege. This is because the provisions on consignation are not applicable when there is

no obligation to pay. A contract to sell involves the performance of an obligation, not merely the exercise of a

privilege or a right. Consequently, performance or payment may be effected not by tender of payment alone

but by both tender and consignation.

21.

Adelfa no longer had right to suspend payment after dismissal of civil case against it

Adelfa Properties no longer had the right to suspend payment after the disturbance ceased with the

dismissal of the civil case filed against it. Necessarily, therefore, its obligation to pay the balance again arose

and resumed after it received notice of such dismissal. Unfortunately, Adelfa failed to seasonably make

payment, as in fact it has failed to do so up to the present time, or even to deposit the money with the trial

court when this case was originally filed therein.

Sales, 2003 ( 14 )

Haystacks (Berne Guerrero)

22.

Rescission in a contract to sell

Article 1592 of the Civil Code which requires rescission either by judicial action or notarial act is not

applicable to a contract to sell. Furthermore, judicial action for rescission of a contract is not necessary where

the contract provides for automatic rescission in case of breach, as in the contract involved in the present

controversy. By Adelfa’s failure to comply with its obligation, the Jimenezes elected to resort to and did

announce the rescission of the contract through its letter to Adelfa dated 27 July 1990. That written notice of

rescission is deemed sufficient under the circumstances.

23.

Resolution of reciprocal contracts may be made extrajudicially, unless impugned in court

It was held in University of the Philippines vs. De los Angeles, etc. that the right to rescind is not

absolute, being ever subject to scrutiny and review by the proper court. However, this rule applies to a

situation where the extrajudicial rescission is contested by the defaulting party. In other words, resolution of

reciprocal contracts may be made extrajudicially unless successfully impugned in court. If the debtor impugns

the declaration, it shall be subject to judicial determination. Otherwise, if said party does not oppose it, the

extrajudicial rescission shall have legal effect. In the present case, although Adelfa Properties was duly

furnished and did receive a written notice of rescission which specified the grounds therefore, it failed to reply

thereto or protest against it. Its silence thereon suggests an admission of the veracity and validity of

Jimenezes’ claim.

24.

Adelfa estopped

Furthermore, the initiative of instituting suit was transferred from the rescinder to the defaulter by

virtue of the automatic rescission clause in the contract. But then, aside from the lackadaisical manner with

which Adelfa Properties treated the Jimenezes’ letter of cancellation, it utterly failed to seriously seek redress

from the court for the enforcement of its alleged rights under the contract. If the Jimenezes had not taken the

initiative of filing Civil Case 7532, evidently Adelfa had no intention to take any legal action to compel

specific performance from the former. By such cavalier disregard, it has been effectively estopped from

seeking the affirmative relief it desires but which it had theretofore disdained.

[5]

Agricultural and Home Extension Development Group vs. CA [G.R. No. 92310. September 3, 1992.]

First Division, Cruz (J): 3 concurring

Facts: On 29 March 1972, the spouses Andres Diaz and Josefa Mia sold to Bruno Gundran a 19-hectare

parcel of land in Las Piñas, Rizal, covered by TCT 287416. The owner’s duplicate copy of the title was turned

over to Gundran. However, he did not register the Deed of Absolute Sale because he said he was advised in

the Office of the Register of Deeds of Pasig of the existence of notices of lis pendens on the title. On 20

November 1972, Gundran and Agricultural and Home Development Group (AHDG) entered into a Joint

Venture Agreement for the improvement and subdivision of the land. This agreement was also not annotated

on the title. On 30 August 1976, the spouses Andres Diaz and Josefa Mia again entered into another contract

of sale of the same property with Librado Cabautan. On 3 September 1976, by virtue of an order of the CFI

Rizal, a new owner’s copy of the certificate of title was issued to the Diaz spouses, who had alleged the loss

of their copy. On that same date, the notices of lis pendens annotated on TCT 287416 were canceled and the

Deed of Sale in favor of Cabautan was recorded. A new TCT S-33850/T-172 was thereupon issued in his

name in lieu of the canceled TCT 287416.

On 14 March 1977, Gundran instituted an action for reconveyance before the CFI Pasay City * against