The globalization of the “anti-globalizers”: A transnational network

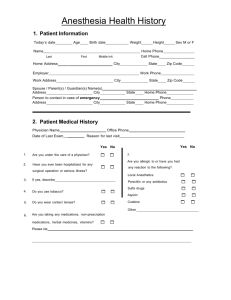

advertisement