Pulsatile Lavage for Pressure ulcer management in spinal cord Injury

advertisement

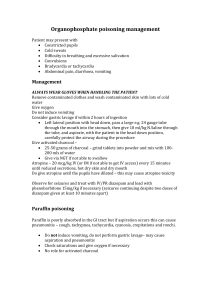

Feature TE Pulsatile Lavage for Pressure Ulcer Management in Spinal Cord Injury: A Retrospective Clinical Safety Review A Kath M. Bogie, DPhil; and Chester H. Ho, MD Abstract PL IC Pressure ulcers are major complications of reduced mobility and/or sensation. Pulsatile lavage therapy delivers localized hydrotherapy directly to the wound utilizing a pulsatile pressurized stream of normal saline. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical safety of pulsatile lavage therapy, provided daily at the bedside, in routine management of Stage III and Stage IV pressure ulcers. Charts from 28 male patients with Stage III and Stage IV pressure ulcers and spinal cord injury (SCI) or spinal cord disorders (SCD) were retrospectively reviewed for documentation of adverse events/safety concerns. Mean therapy duration was 46 days (SD 37 days, range 6–152 days). Treatment was interrupted for 6 days in one patient due to minor wound bleeding. No other adverse events, including backsplash injuries, were documented. The results of this chart review suggest pulsatile lavage therapy can be administered at the patient’s bedside without adverse events if appropriate protocols are followed. Additional research to confirm the efficacy and effectiveness of this treatment modality in a broader subject population is warranted. U Keywords: pressure ulcer, hydrotherapy, pelvic, clinical safety, spinal cord injury Index: Ostomy Wound Management 2013;59(3):35–38 D Potential Conflicts of Interest: none disclosed P D O N O T ressure ulcers (PUs) remain a major medical complication for many individuals with reduced mobility and/ or sensation. Treatment costs for an individual PU can vary greatly depending on factors such as prolonged hospitalization and surgery. A 2010 cost-analysis1 of 12 Canadian community dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) found an average monthly cost of $4,745 (the total cost per PU was not defined). A 2010 retrospective chart review2 of inpatient (N = 19) costs associated with the care of Stage IV PUs found average costs to be more than $120,000 per ulcer. PUs are the main cause for readmission in the SCI and SCI disorders (SCI/D) population,3 leading to reduced independence and decreased quality of life. In the general field of rehabilitation, it is well established that the development of a PU will increase both medical costs and length of stay.4 Timely and effective treatment of PUs is a central requirement for suc- cessful care outcomes, and many different treatment options are available. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP)/European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) Clinical Guidelines5 indicate only two specialized treatment modalities can be recommended to enhance wound healing, one of which is hydrotherapy. Hydrotherapy was previously implemented as whirlpool therapy and has been found to be effective in a case-controlled study design,6 where the control group (n = 18) received conservative treatment alone (maximization of pressure relief and twice-daily wet-to-wet dressing with normal saline) and the intervention group (n = 24) received conservative treatment plus whirlpool therapy for 20 minutes daily. Wound dimension measurement indicated that wounds in the intervention group improved significantly faster than those in the control group. However, whirlpool has become less popular due to its labor- and time-intensive Dr. Bogie is a Senior Research Scientist and Assistant Professor, Advanced Platform Technology Center, a VA Research Center of Excellence, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center; and Assistant Professor, Departments of Orthopedics and Biomedical Engineering, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH. Dr. Ho is an Associate Professor and Head of the Division, Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Foothills Hospital, Calgary, Alberta, Canada; and at the time of manuscript preparation, Chief, SCI/D Service at the Spinal Cord Injury Unit, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Please address correspondence to: Kath M. Bogie, DPhil, Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, APT Center of Excellence, 151 vAW/APTLSCDVAMC, 10701 East Boulevard, Cleveland, OH; email: kmb3@case.edu. www.o-wm.com march 2013 ostomy wound management® 35 Feature Ostomy Wound Management 2013;59(3):35–38 IC A TE Key Points • Historically, the use of hydrotherapy through whirlpool treatments was recommended for the management of a variety of chronic wounds, including pressure ulcers. • Because cross-contamination is an important concern, hydrotherapy methods have been replaced by the use of single-patient equipment to administer pulsatile lavage. • Clinical studies documenting the outcomes of this treatment modality in pressure ulcers are limited; safety concerns remain. • Researchers did not find evidence of serious adverse reactions in the charts of 28 patients who underwent pulsatile lavage therapy for their Stage III and Stage IV pressure ulcers. • Additional safety studies, as well as evidence to support the efficacy and effectiveness of this treatment modality, are warranted. PL mode of delivery combined with an unacceptable potential for complications, as reported in two infection control studies.7,8 A case study9 reported bilateral amputations in a paraplegic patient due to hydrotherapy burns. Pulsatile lavage therapy delivers localized hydrotherapy directly to the wound area utilizing a pulsatile pressurized stream of normal saline. The treatment is delivered through a single-patient use device with a disposable tip. This technique has been used for many years for intra-operative joint cleansing in the field of orthopedic surgery.10 A trained nurse can administer pulsatile lavage. The use of pulsatile lavage has been less widespread in the field of wound care and mostly focused on the debridement of necrotic wounds. In a double-blind study11 conducted among 28 persons with SCI/D, the effects of pulsatile lavage were assessed in clinically clean ulcers that did not require debridement. In this study, persons with SCD and a Stage III or Stage IV pelvic PU were randomized to a treatment (n = 14) and a control group (n = 14) of dressing changes and maintenance of a moist wound environment. Wound dimensions decreased more rapidly in the pulsatile lavage group, leading to statistically significant differences in healing rate between the treatment and control groups for wound length and width (P <0.0001) and depth and volume (P <0.001). Even though the clinical impression of therapy recipients was that pulsatile lavage was a safe treatment modality, to date, a literature review has shown no published systematic review of the clinical safety aspects of this treatment modality. No adverse effects were seen in the previous study11; however, a study12 of clinical practice at the Johns Hopkins Hospital described an outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDR-Ab) associated with pulsatile lavage wound treatment during inpatient hospitalization. An outbreak, case-control investigation of seven patients identified as infected or colonized with MDR-Ab were compared to 28 controls without MDR-Ab infection. It was suggested that extensive environmental contamination occurred during pulsatile lavage, which led to transmission of a multi-resistant strain of Acinetobacter from patient to patient. In addition to systemic infection or sepsis, patientcentered adverse event parameters that could occur due to the biophysical nature of pulsatile lavage therapy should be examined in order to determine clinical safety. Thus, in addition to de novo wound infection as a result of the therapy and presence of sepsis, potential adverse events that could occur due to pulsatile lavage therapy include pain and bleeding. Pulsatile lavage therapy is delivered directly to the wound area with concurrent suction to remove the contaminated lavage fluid. The concurrent application of suction, albeit at a relatively low level, has the potential to cause pain and/or bleeding. Autonomic dysreflexia is a potentially serious outcome in persons with SCI/D with a neurologic level of injury at or above T6, secondary to unopposed sympathetic output of D O N O T D U the autonomic nervous system when a noxious stimulus is detected by the sensory system. It could lead to hypertensive crisis, which could then result in myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident.13,14 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical safety of pulsatile lavage therapy in routine management of Stage III and Stage IV PUs. 36 ostomy wound management® March 2013 Methods A retrospective chart review was conducted of individuals with SCI/D who had pelvic region PUs treated by pulsatile lavage at the authors’ facility over the same time frame as persons studied concurrently in a blinded clinical study.11 During the 3-week study, pulsatile lavage was administered daily in the patient’s room, with the patient in his/her own bed, for 10 to 20 minutes by trained nursing staff using the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Stryker Interpulse system (Stryker Instruments, Kalamazoo MI). This system consists of a battery-powered pump device that produces the water spray effect for the lavage. Pulsatile lavage therapy is delivered directly over the PU at a distance of 0.5–2 inches from the wound bed. The pump device provides a water spray pressure of 11 lb per square inch (psi) — ie, within the recommended low pressure range of 4–15 psi.5 A 1-L bag of sterile normal saline was used as the source of the water spray, and the pump device was attached to it during the lavage. The water spray was delivered through a detachable fan shower spray. Concurrently, water suction was provided at the tip of the fan spray. The shape of the fan spray and the concurrent water suction ensured that contaminated lavage fluid was immediately removed from the wound area www.o-wm.com Pulsatile lavage safety Table 1. Pulsatile lavage treatment adverse event outcomes abstracted Measurement Y/N Development of systemic infection (sepsis) Y/N Pain Y/N Bleeding from the ulcer Y/N Presence of autonomic dysreflexia Y/N Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse event Y/N A Development of pressure ulcer infection TE Patient-centered Clinician safety Splash injury Y/N PL and collected in a disposable canister, preventing accidental splashing of the lavage fluid during the procedure. The system is single-patient use only, and a new lavage tip is used for each treatment. Clinical personnel wore protective garments and goggles while administering the treatment. Protective drapes were placed on the bed and around the wound area. Chart review procedure. The study protocol was deemed exempt by the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Review Board. In addition to patient demographic and PU information, both patient-centered and clinician safety variables were reviewed and abstracted. Charts were initially reviewed for documentation of all adverse events during the time frame during which pulsatile lavage treatment was administered; specifically, PU depth (stage), wound area, location, infection status, and presence/absence of necrotic tissue were abstracted. A secondary detailed chart review then was performed to determine if the adverse event had any association with delivery of pulsatile lavage treatment. For example, a report of autonomic dysreflexia during bowel care would initially be listed as an adverse event, but on secondary review it would be determined it was unrelated to lavage therapy. Patient-centered safety variables abstracted included development of PU-related infection, development of systemic infection (sepsis), pain, bleeding from the ulcer, and/or presence of autonomic dysreflexia using a yes/no notation (see Table 1). A clinical safety review was carried out of adverse events occurring related to the therapeutic intervention for both the treatment cohort and the clinicians providing pulsatile lavage therapy. The occurrence of adverse events reported by the administering clinical provider, specifically splash injury, was abstracted as a clinical safety variable. A Quality Improvement nurse familiar with this patient population and PU treatment completed the chart review. Data collection. Data were extracted from the medical chart in the computerized patient record system (CPRS) and stored in a de-identified Excel spreadsheet. IC Parameter Results The treatment cohort comprised 28 men, several of whom had multiple ulcers; a total of 38 Stage III and Stage IV pelvic region PUs were provided pulsatile lavage. Within this cohort, 28 individuals had one, nine had two, and one had three PUs, for which therapy was provided. Twelve patients were tetraplegic and 17 were level A status per American Spinal Cord Injury Impairment Status (AIS) — ie, no motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-S5 (see Table 2). The majority of PUs were in the sacral (47%) or ischial (45%) regions. Mean pulsatile lavage therapy duration was 46 days (SD 37 days, range 6–152 days). Treatment was temporarily discontinued in one patient due to mild bleeding from the wound and resumed 6 days later without any further problem. Treatment was discontinued in one patient due to rapid improvement in the wound size and in another due to a concurrent fever of unknown origin. No splash injury to any clinical care provider administering pulsatile lavage therapy was documented, and no other adverse events or treatment discontinuations were documented. D O N O T D U Discussion Although whirlpool therapy is effective,6 its limitations for PU care — especially the risk of cross-contamination — have made clinical usage obsolete. Pulsatile lavage utilizes a singlepatient system and was found to be well-accepted when used to treat Stage III and Stage IV PUs.11 Not only has the authors’ research previously shown that pulsatile lavage was clinically efficacious, but it has also demonstrated that given the appropriate infection control precautions as described in the current methodology, low-pressure pulsatile lavage is not associated with an increased rate of environmental contamination.15 The current study is first to report on the clinical safety of pulsatile lavage and did not identify any serious patient- or clinicial-related adverse events, such as splashing. Although environmental contamination was not evaluated in this retrospective chart review, it is important to note that a previous report of an outbreak among inpatients who received pulsatile lavage therapy in clinical practice at the Johns Hopkins Hospital was attributed by the authors mainly to two practices that negatively affected infection control12: the use of a common wound care treatment area for pulsatile lavage and use of the same suction canister for all the patients. A safe treatment protocol must incorporate infection control practices, including single-patient use systems. In addition, a new lavage tip is required for each treatment. Clinical personnel must wear personal protection equipment, including protective garments and goggles, during delivery of pulsatile lavage treatment, and the wound area must be draped. The results of this chart review suggest that pulsatile lavage therapy can be administered at the patient’s bedside without adverse events if appropriate protocols are followed. Additional research to confirm the safety and establish the efficacy and effectiveness of this treatment modality is warranted. www.o-wm.com march 2013 ostomy wound management® 37 Feature Table 2. Patient demographic characteristics Level of injury AIS status a a Mean 55 Tetraplegic 12 A 17 SD 10 B 3 Minimum 37 Maximum 74 Paraplegic 12 MS 4 C 3 D 0 Four individuals had a primary diagnosis of multiple sclerosis; AIS = American Spinal Cord Injury Impairment Status Sacral 18 Ischial 17 Stage (n) III 8 IV 30 Size (n)a <10 cm2 10 10 to <50 cm2 18 Pre-existing clinical wound Yes infection (n)a 7 No 31 Pre-existing wound tissue necrosis (n)a 13 No 25 5 3 50 to <100 cm2 7 >100 cm2 3 PL a Yes Trochanteric IC Location (n) A Table 3: Pressure ulcer characteristics N/A TE Age (years) Surface area References 1. Chan BC, Nanwa N, Mittmann N, Bryant D, Coyte PC, Houghton PE. The average cost of pressure ulcer management in a community dwelling spinal cord injury population. Int Wound J. 2012;doi: 10.1111/j.1742481X.2012.01002.x. PMID: 22715990. 2. Brem H, Maggi J, Nierman D, Rolnitzky L, Bell D, Rennert R, et al. High cost of Stage IV pressure ulcers. Am J Surg. 2010(4):473–477. 3. Chen D, Apple DF Jr, Hudson LM, Bode R. Medical complications during acute rehabilitation following spinal cord injury — current experience of the Model System. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(11):1397–1401. 4. Allman RM, Goode PS, Burst N, Bartolucci AA, Thomas DR. Pressure ulcers, hospital complications, and disease severity: impact on hospital costs and length of stay. Adv Wound Care. 1999;12(1):22–30. 5. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcer treatment recommendations. In: Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: clinical practice guideline. Washington (DC): National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2009. Available at: www,NPUAP. org. Accessed February 25, 2013. 6. Burke DT, Ho CH, Saucier MA, Stewart G. Effects of hydrotherapy on pressure ulcer healing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;77(5):394–398. 7. McMillan J, Hargiss C, Nourse A, Williams O. Procedure for decontamination of hydrotherapy equipment. Phys Ther. 1976;56(5):567–570. 8. Nelson RM, Reed JR, Kenton DM. Microbiological evaluation of decontamination procedures for hydrotherapy tanks. Phys Ther. 1972;52:919–924. 9. Hwang JC, Himel HN, Edlich RF. Bilateral amputations following hydrotherapy tank burns in a paraplegic patient. Burns. 1995;21(1):70–71. 10. Sobel JW, Goldberg VM. Pulsatile irrigation in orthopedics. Orthopedics. 1985;8(8):1019–1022. 11. Ho CH, Bensitel T, Wang X, Bogie KM. Pulsatile lavage for the enhancement of pressure ulcer healing: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2012;92(1):38–48. 12. Maragakis LL, Cosgrove SE, Song X, Kim D, Rosenbaum P, Ciesla N, et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii associated with pulsatile lavage wound treatment. JAMA. 2004;292(24):3006–3011. 13. Dolinak D, Balraj E. Autonomic dysflexia and sudden death in people with traumatic spinal cord injury. Am J Forensic Med Pathos. 2007;28(2):95–98. 14.Karlsson AK. Autonomic dysfunction in spinal cord injury: clinical presentation of symptoms and signs. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:1–8. 15. Ho CH, Johnson T, Miklacic J, Donskey CJ. Is the use of pulsatile lavage for pressure ulcer management associated with environmental contamination with Acinetobacter baumannii? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(10):1723–1726. D U Limitations The most important limitation of this study is the retrospective design, which introduces risks of charting omissions, errors, and clinician bias. In addition, the sample size was small and treatment duration varied. N O T Conclusion Aretrospectivechart review was conducted to evaluate the clinical safety of pulsatile lavage for the treatment of Stage III and Stage IV PUs in individuals with SCI/D in routine clinical management. An interruption in treatment was documented for one of 28 patients due to minor wound bleeding. No other adverse events, including autonomic dysreflexia and splash injury, were recorded. In this small study, pulsatile lavage provided a safe form of hydrotherapy for the treatment of Stage III and Stage IV pressure ulcers in persons with SCI/D. n D O Acknowledgments The authors acknowledge the VA for indirect support provided through access to VA resources. Identifiers were removed for blinding of reviewers. The authors are grateful to Robin Blake, RN, MSN, DNP, CNS, who carried out the retrospective chart review. 38 ostomy wound management® March 2013 www.o-wm.com