Applying Real-World BPM in an SAP Environment

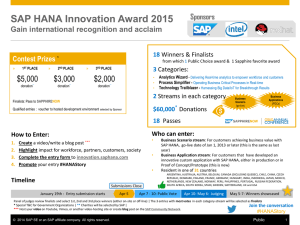

advertisement