57. Enter the Badvocate: A Unique Consumer

advertisement

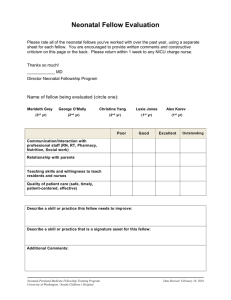

57. Enter the Badvocate: A Unique Consumer Role Emerging Within Social Media Complaint and Recovery Episodes Todd J. Bacile, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Marketing Joseph A. Butt, S.J., College of Business Loyola University New Orleans New Orleans, LA, U.S.A. tjbacile@loyno.edu Alexis Allen, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Marketing Gatton College of Business and Economics University of Kentucky Lexington, KY, U.S.A. alexis.allen@uky.edu Charles F. Hofacker, Ph.D. Professor of Marketing College of Business Florida State University Tallahassee, FL, U.S.A. chofack@cob.fsu.edu 1 Abstract This research identifies the “badvocate” as a new consumer role in which a consumer brand advocate engages in dysfunctional behavior during service encounters on brands’ social media pages. Whereas past research primarily views firm – consumer service channels from a dyadic perspective in which only two parties are present, the current research considers the expanding impact of social media channels, where multiple consumers may be present and participate during complaint and service recovery episodes. The netnographic method is utilized to analyze over 1,400 consumer message threads from firms’ Facebook walls. The analysis leads the authors to develop five propositions relating to the impact of the badvocate when piercing the traditional service dyad. The findings and resulting propositions support the importance for practitioners to recognize this new consumer role, and suggest avenues of future research for academics. Traditional offline customer service encounters involve a dyad including a customer seeking assistance and a service provider (Solomon et al. 1985). However, social media are altering the composition of the dyad. Firms’ social media pages are emerging as viable customer service channels (Gallaugher and Ransbotham 2010), which introduce the possibility for multiple consumers to actively participate during online service encounters and service recovery attempts. This may be acceptable to firms if fellow consumers who interject within the service dyad behave functionally and appropriately. However, appropriate behavior is not a given when considering that some consumers in offline interactions do not behave in a positive manner (Grove and Fisk 1997). Moreover, different consumer roles illustrate that not all customers are considered equally desirable (Bitner, Booms, and Tetreault 1990). The most basic consumer role performance is a customer purchasing and consuming a product (Solomon et al. 1985). From a firm’s perspective a more attractive role is one in which a consumer repeatedly buys a product to become a loyal customer (Oliver 1999). An additional role is a customer who transcends loyalty to become a brand advocate (Bendapudi and Berry 1997). The brand advocate role includes the performance of positive extra-role behavior, such as assisting others, customer recruitment, and positive word-of-mouth referrals. At the other end of the proverbial spectrum are consumers who perform negative, unexpected roles (Bitner, Booms, and Mohr 1994) to the point of becoming dysfunctional consumers by acting in a rude, uncivil, or disruptive manner (Harris and Reynolds 2003). Interestingly, research examines different consumer roles as distinct from one another with little overlap. For example, no 2 research examines a loyal customer or a brand advocate who, at times, will also act out as a dysfunctional consumer. However, there is anecdotal evidence of loyal consumers using social media to act out in a dysfunctional manner (e.g., Luckerson 2013). Therefore, research has no answer as to propositions, theories, antecedents, or consequences of a loyal consumer advocate simultaneously acting in a dysfunctional manner and how such a consumer’s actions affect other consumers or a firm itself. The purpose of this study is to begin filling this gap by examining a unique consumer role -- part dysfunctional consumer and part brand advocate -- that is emerging during social media customer service encounters. An initial exploration is made to illuminate this type of consumer’s activity and how such behavior affects fellow consumers who witness or participate in these communication exchanges within social media. The researchers label this new type of consumer as a badvocate and present five research propositions as to how this new role affects consumers and firms, specifically in online service encounters and service recovery episodes which unfold on brand-owned social media channels. The overarching research question guiding this investigation is: what challenges do badvocates introduce during service recovery opportunities via social media? The particular scope is when badvocates target fellow consumers on a firm’s social media page during service encounters. Due to the emergent nature of this new role along with a dearth of relevant literature, a netnographic study (Kozinets 2002) is conducted to understand the phenomenon under investigation and to initiate theory generation on the subject. The pursuit to understand the phenomenon more thoroughly and anchor it with theory should provide both practitioners and theorists with implications and areas of further research in the domains of managing service encounters via social media, complaint handling and service recovery, and the challenges associated with a new consumer role that encompasses both dysfunctional consumers and brand advocates. The remainder of this paper begins with an overview of research areas that are converging in regard to the phenomenon under study. Concepts relating to customer service encounters are briefly covered, followed by a review of dysfunctional consumers, loyal consumers, and brand advocates. The literature review is followed by the research methodology, which provides results linking the theoretical domain of 3 complaint handling and service recovery. The product of the results allows for the introduction of research propositions. The article concludes with implications and areas of future research. Literature Review Service Encounters and Service Recovery A service encounter is the interaction a consumer has with a firm’s customer service personnel and ranges from consumers purchasing a service product, seeking general assistance, or voicing complaints (Bitner, Booms, and Tetreault 1990). Traditional customer service encounters involve a dyad consisting of an assistance-seeking consumer and firm’s service representative (Solomon et al. 1985). When service encounters move beyond simply providing assistance, such as answering routine questions, a heightened state of action may be required of a firm. Consumers voice complaints after a negative experience with a product, service, or interactions with a firm. In this manner a complaint is a service request taken by a consumer to address a dissatisfying outcome or failure by a firm (Day and Landon 1977). The following actions taken by a firm in an attempt to resolve an issue attributed to a previous failure are known as a service recovery (Grönroos 1988), with a firm’s complaint handling strategy acting as a key factor determining the success of a recovery (Bitner 1990). An effective recovery resolves an initial complaint, while also bolstering customer loyalty, satisfaction, word-of-mouth referrals, and the customer-firm bond (Hart, Heskett, and Sasser 1990; Smith, Bolton, and Wagner 1999). Consumers assess the quality of a firm’s service recovery effort using three dimensions of perceived justice (Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran 1998). These fairness dimensions are drawn from organizational justice research, which assesses the fairness within a workplace (Bies and Moag 1986). Interactional justice refers to how fair a consumer’s perception is of the treatment or communication by customer service personnel, such as the degree of respectful, prompt, or polite interactions (Blodgett, Hill, and Tax 1997). Procedural justice refers to how fair a consumer’s perception is of the policies and procedures, decision making, and conflict resolution authority used by personnel during a service recovery 4 (Thibaut and Walker 1975). Moreover, procedural justice includes the fairness of the complaint handling process (Blodgett, Granbois, and Walters 1993). Distributive justice refers to how fair a consumer’s perception is of the outcome of a service encounter (Gelbrich and Roschk 2011). It is the subjective benefit a consumer receives from a firm to make up for a failure, and includes economic compensation or psychological compensation such as a sincere apology (Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran 1998). Dysfunctional Consumers, Loyal Consumers, and Brand Advocates In an effort to present an emergent consumer role posing new challenges to marketers during service encounters, a review of the literature presents several unique types of consumers. At the core of each type is a person who behaves or acts in one of several possible consumer roles (Bettencourt 1997; Bitner et al. 1997; Solomon et al. 1985). Panel A in Table 1 represents a typology of various consumers. ---------------------------------------------------INSERT TABLE 1 – PANEL A - ABOUT HERE ---------------------------------------------------A dysfunctional consumer is someone who behaves inappropriately in a way that disrupts otherwise functional encounters for fellow consumers and/or employees of a firm (Harris and Reynolds 2003). The dysfunctional consumer label is synonymous with related labels in the literature, such as problem customers (Bitner, Booms, and Mohr 1994), unfair customers (Berry and Seiders 2008), and jaycustomers (Lovelock 1994). Types of dysfunctional behavior include verbal abuse, rudeness, disrespectful language, intimidation, threatening behavior, violation of rules, or theft (Fisk et al. 2010). The consequences of dysfunctional behavior affect consumers, employees, and the firm itself. Consumers who fall victim to or merely witness such behavior experience dissatisfaction with a firm (Grove and Fisk 1997; Reynolds and Harris 2009), lower customer loyalty (Harris and Reynolds 2003), and several other negative behavioral and psychological effects (Fisk et al. 2010). Frontline employees also experience negative physical effects, cognitions, emotions, and behaviors (Rupp and Spencer 2006). 5 The underlying theoretical driver by which people distinguish between acceptable and dysfunctional behavior resides within sociological deviance theory. Deviance is socially recognized problem behavior that is a source of concern or an undesirable act based upon norms within a social environment (Osgood et al. 1988). Closely associated with deviance are social norms, which are commonly held beliefs about how an individual should act within a social environment such as a community, organization, or group setting (Kahneman and Miller 1986). Deviant behavior occurs when the threshold of unwritten social norms are violated in a given setting. Minor deviant acts of incivility such as rude and impolite language (Andersson and Pearson 1999) are popular and damaging to individuals and companies (Cortina et al. 2001). A victim (i.e., the target of incivility) or a bystander (i.e., witnesses of incivility) can each be affected negatively (Phillips and Smith 2003). Merely being a bystander who witnesses incivility produces feelings of anger, fear, unease, and distrust (Phillips and Smith 2004). In addition, incivility from peers may cause targets and bystanders to hold an institution or entity liable for failing to maintain expected social norms (Caza and Cortina 2007). A contrast to a dysfunctional consumer is a loyal consumer. Consumers can exhibit attitudinal loyalty (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001) and/or behavioral loyalty (e.g., re-purchasing; Oliver 1999). In combination types of loyalty reside in a sequential chain moving from cognitive loyalty to affective loyalty to conative loyalty to action (i.e. purchasing) loyalty (Harris and Goode 2004). Marketers seek to attain loyal customers due to the associations that loyalty constructs have with other positive constructs, such as perceived value, satisfaction, and customer lifetime value (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001). To move beyond a loyal customer is one who, in addition to making repeated purchases, will perform positive extra-role behaviors which benefit a firm (Bettencourt 1997). The current study adopts the consumer label of brand advocate (Smith and Wheeler 2002) to represent a heightened state of loyalty with the addition of positive extra-role behavior performed by a loyal consumer. Positioning brand advocates in this perspective tabs the advocates as extremely active loyalists who are committed and passionate about a 6 brand (Gruen and Ferguson 1994). Brand advocates are suggested to be a step above a loyal customer, which is why brands seek to “manage the development of relationships with customers which evolve from their satisfaction to loyalty and then to advocacy,” (Chen and Vargo 2008, p. 124). Such consumer advocates may offer extra-role behaviors such as positive word-of-mouth, customer recruitment, function as partial employees to assist others, and may even go so far as to defend a brand when it comes under attack by others (Bendapudi and Berry 1997; Rosenbaum and Massiah 2007). Even though brand advocates are an extremely attractive type of consumer there is limited research, conceptualizations, and theories devoted to advocates. Most references are fleeting in the loyalty-related literature streams in the form of brief mentions of advocates and advocacy as positive outcomes or secondary byproducts of other focal concepts (e.g. Bendapudi and Berry 1997; Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Harris and Goode 2004). Regardless of researchers’ inattention to focusing on brand advocates, there is little debate that a loyal consumer who performs positive extra-role behaviors is a desirable asset to a firm. Panel B in Table 1 depicts several consumer types along a continuum of desirability from a firm’s perspective. Dysfunctional consumers produce lower or negative value by causing a firm to experience a reduction in the loyalty of fellow consumers and other negative effects. The next three customer types are based upon purchase frequency, with the notion that repeated purchases produce more economic and relationship value. Finally, brand advocates add to the attractiveness of loyal customers with the addition of positive extra-role behavior. A dilemma never before recognized within marketing is if the two consumer types at the polar ends of Panel B within Table 1’s continuum were to merge into a unique type of consumer who interjects during a complaint and recovery encounter. The present paper contends that such a role is surfacing online, which is consistent with the position that new interactive technologies create the emergence of new consumer roles (Deighton and Kornfeld 2009). The following study attempts to uncover and understand the ramifications of this new role. 7 ---------------------------------------------------INSERT TABLE 1 – PANEL B - ABOUT HERE ---------------------------------------------------Methodology Research Design and Method Due to the lack of understanding and absence of literature for badvocates, a design focusing on theory generation by exploring and developing the focal concept was selected over immediate causal research (Strauss and Corbin 1998). A qualitative method in the form of a netnographic study seemed ideal due to the online nature of social media. Netnography is ethnography on the Internet, which is a newer form of the qualitative research approach to adapt to the study of emerging cultures and communities taking place through computer-mediated communications (Kozinets 1998, 1999, 2002). A strong point of netnography is its unobtrusiveness while still being able to discern valuable information (Kozinets 2002). The netnographic method uses information that is publicly viewable on the Internet to identify and understand online activities. The observations arise from a natural setting not fabricated by the researcher. This method is unique, as pointed out by Kozinets (2002, p.62), “[n]etnography provides marketing researchers with a window into naturally occurring behaviors, such as searches for information by and communal word of mouth between consumers. Because it is both naturalistic and unobtrusive - a unique combination not found in any other marketing research method - netnography allows continuing access to informants in a particular online social situation.” Using netnography to investigate this phenomenon enables the researchers to examine actual consumer communication exchanges, rather than using fictitious hypothetical scenarios. To date this method has been used successfully in several research studies (e.g. Brown, Kozinets, and Sherry 2003; Kozinets 2002; Kozinets and Handelman 2004; Pan and Zhang 2011). Design and Data Collection Two brands’ Facebook pages provided the data used to answer the overarching research question. One each of the largest hotel chains and retailer chains based on gross U.S. sales were selected. Both 8 brands’ Facebook pages met Kozinets’ (1999) requirements for suitable online communities: they were relevant groups for the research question, a high number of messages were posted, a high number of discrete message posters were present, the information shared was detailed and rich, and the interactions were relevant to the research question. A continuous 30-day block of Facebook wall posts (i.e. message threads on a brand’s Facebook page) created by consumers and responded to by fellow consumers or the brand were collected at two different time periods: one 30-day block in 2012 and one 30-day block in 2013 for each firm. Posts from both years were used to assess if some of the consumer message posters were present across multiple years in an effort to identify some loyal customers of a firm. All of the messages were reviewed numerous times to code various elements. Thus, the data within this examination was solely based upon textual observations, which is a necessary aspect of netnography in comparison with ethnography (Kozinets 2002). Repetitive themes and categories were recorded separately by two researchers. Discrepancies were discussed and ultimately agreed upon. Research Findings The focus of this study was on the challenges related to a new role emerging within the context of online customer service channels. Consistent with this context, the analysis revealed the popularity of brands’ social media pages as a service channel. Table 2 includes a list of the various types of message threads authored by consumers on the brands’ social media pages. Across both firms a total of 822 out of 1,434 (57%) of the message threads were categorized as a “service” request, which illustrated consumers’ expectations of customer service via social media. Within these service threads two distinct types were identified. First, 54% of the service threads were categorized as a “complaint and recovery opportunity”. These threads featured a consumer discussing a poor experience with a product, a service, personnel, or some other dissatisfying aspect related to a firm. Second, 46% of the service threads were categorized as a “general question / support”. These service-related requests included general questions; and did not include dissatisfying comments associated with complaints. Table 2 contains a full list of the non-service categories 9 as well. With the research question seeking to understand how other consumers interject during a complaint and recovery opportunity, the researchers focused on the 441 complaint-related message threads. ---------------------------------------------------INSERT TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE ---------------------------------------------------The Emergence of the Badvocate The results of the analysis showed the two primary parties within the traditional service dyad joined by several others in these social communication exchanges. Approximately 50% of complaint and recovery opportunity message threads involved a person other than the original complainant or a firm’s service representative responding to an initial complaint (58% for the retailer and 34% for the hotel). In effect, the service dyad was commonly penetrated by other consumers within service recovery opportunities via social media. Those who interjected during the complaint and recovery process were broadly labeled as “fellow consumers”. When examining the details of their message posts the following types of fellow consumers were identified: “actively sided with the complainant”; “actively sided with the brand”; and “actively posted miscellaneous comments”. Fellow consumers who sided with the complainant posted responses conveying sympathy for the service failure, wished the complainant luck with resolving the issue, or agreed with the subject of the complaint after experiencing a similar issue sometime in the past. In contrast, fellow consumers who actively sided with the brand took it upon his or herself to say why a complainant or some other uncontrollable factor was the cause of the dissatisfying event. Moreover, fellow consumers who actively sided with the brand tended to shift the cause of a failure away from the brand and either toward the complainant or toward some other cause that was beyond the firm’s control. In their view a service failure did not occur. Fellow consumers who actively sided with the brand used comments and details in their communications to suggest that they were a repeat customer who possessed a large amount of knowledge of the firm’s products, services, operational processes, or other characteristics of the company. Several of these fellow consumers also posted often in several threads. It was apparent that this type of fellow consumer possessed knowledge akin to a loyal customer; and elected to repeatedly 10 perform extra-role behavior by attempting to assist a brand by defending it. These types of responses were not surprising if these fellow consumers are recognized as brand advocates. Such advocates have been known to operate as partial employees by attending to the concerns of other consumers; and have been known to defend their beloved brand when perceiving it to be under attack by others. The analysis revealed another phenomenon regarding fellow consumers who sided with the brand: several of their responses included rude language, sarcasm to belittle, accusations of lying, or insults toward a complainant. Moreover, a theme that emerged was “uncivil responses” from some fellow consumers who actively sided with the brand. Table 3 contains some examples. When logically assessing the situation of a complainant seeking assistance from the firm to address a failure, such uncivil responses from fellow consumers seemed to violate commonly accepted social norms. These types of responses seemed unnecessary and out of place during a recovery attempt. In this manner, uncivil fellow consumers exhibited characteristics associated with dysfunctional consumers. To state this in an alternative way, the analysis identified brand advocates who were simultaneously acting as dysfunctional consumers. ---------------------------------------------------INSERT TABLE 3 ABOUT HERE ---------------------------------------------------The analysis of these uncivil responses revealed the following two criteria. First, the fellow consumer was in support of or defended the firm. Second, the fellow consumer’s comments contained uncivil language, rude comments, or accusations of lying directed toward the complainant. Marketing literature suggests that consumers who exhibit only the first criteria are labeled as brand advocates who are supporting or defending their favored brand. The literature also suggests that consumers who exhibit only the second criteria are labeled as dysfunctional consumers who are acting in a problematic way that disrupts a functional service encounter. However, there is nothing in marketing research that discusses a consumer who possesses both criteria one and two: a brand advocate who behaves badly. Yet, 117 (27%) of the complaint and recovery opportunity threads (30% for the retailer and 19% for the hotel) included a consumer who possessed the two criteria as evident in several of their responses. In addition, this type of 11 consumer existed in the data across both firms, which were in different industries. Hence, a unique type of consumer emerged, which combined some characteristics of a dysfunctional consumer (e.g. treating other consumers rudely while disrupting the functional recovery process) along with some characteristics of a brand advocate (e.g. supporting the brand, stating positive things about the brand, and defending the brand against a perceived naysayer). The present study labels this consumer as a badvocate. P1: a badvocate is a unique type of consumer, which blends characteristics of a dysfunctional consumer with characteristics of a brand advocate; and this type of consumer is emerging within service encounters online via social media channels. The anonymity of the Internet (i.e. online users maintaining some degree of anonymity in a virtual environment) affords people the opportunity to act differently compared to an in-person encounter (Christopherson 2007). Anonymity can create a deindividuated state in some people (Zimbardo 1969), whereby a person is more willing to violate social norms. Anonymity theory (Pedersen 1997) applied to the remote connectivity of the Internet posits that consumers become more brazen and opinionated under the protection of a remote encounter with others. Even when a person’s identity is not 100% anonymous, the disconnected lack of a face-to-face in-person encounter serves as a protective barrier (Sun et al. 2006). Anonymity theory, when combined with consumers voicing complaints on a brand’s social media page that is active with brand advocates, helps explain the emergence of the badvocate interjecting within service recovery opportunities via social media. This emergence of the badvocate introduces challenges and complications associated with the assessment of perceived justice. Badvocates Influence Interactional and Procedural Justice The analysis revealed that none of the 117 complaint threads which contained a badvocate’s comments were responded to by a firm in a way that attempted to recognize, address, or apologize for the uncivil responses. Moreover, when a firm responded to a complainant it acted as if it was oblivious to all other responses from fellow consumers. The firm responded as if the service dyad was still intact by only addressing comments from a complainant. By only addressing the original complaint and not addressing 12 rude comments and insults, we posit that a firm’s communication interactions and the overall complaint handling process are perceived as unfair, which impacts interactional and procedural justice, respectively. In a traditional offline service environment a firm is expected to manage the conduct of dysfunctional activities carried out by consumers (Fullerton and Punj 1996). Failing to address such actions may cause consumers exposed to the dysfunction to attribute a portion of the blame to a firm (Huang 2008). The inappropriate actions of a fellow consumer result in a failure itself, which is referred to as othercustomer failure and happens, “when any action by another customer has a negative impact on one’s service experience," (Huang 2008, p. 522). When a firm fails to apologize or recognize badvocate responses in these social media service exchanges, a complainant is likely to view the lack of communication by customer service as unfair, in part due to, “customer expectations regarding interpersonal treatment in the face of a failure are considerably higher than they are in standard service encounter situations,” (Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran 1998, p. 72). Under the domains of fairness theory (Folger and Cropanzano 2001) and attribution theory (Kelley and Michela 1980) customers are likely to assign blame toward a firm for such unfair treatment. We posit that when a firm allows fellow consumers to respond with norm violating responses, a firm’s failure to address the uncivil communications within its social media service environment is likely to be viewed by complainants as unfair interpersonal treatment. This will weaken a complainant’s perceived interactional justice associated with a firm. The lack of interaction by the firm to address a badvocate may also weaken procedural justice perceptions. Procedural justice refers to procedures and conflict resolution used by a firm (Thibaut and Walker 1975). A broader view of procedural justice is the perceived fairness of the complaint handling process (Blodgett, Granbois, and Walters 1993), which not only includes the timeliness of a firm’s response to a complaint, but also the “policies, procedures, and structures a company has in place to provide a smooth complaint handling process,” (Gelbrich and Roschk 2011, p. 26). A firm’s inability to control its complaint handling process by failing to address rude badvocate comments or apologize to a complainant for uncivil comments during a recovery effort creates a questionable complaint handling process. The 13 presence of badvocate comments without intervention or recognition by a firm during a social media complaining and recovery opportunity may signal the lack of a firm being able to fairly manage its recovery process. In the present context we posit that a firm failing to address or recognize rude and uncivil comments made to a complainant creates a procedurally unfair complaint handling process. The analysis also revealed another unique aspect associated with justice perceptions. Traditional service recovery research examines the perception of a complainant, while not focusing on other consumers’ perceptions. In the past this logically made sense because traditional complaint and recovery efforts typically occurred within a service dyad, meaning all other parties were not exposed to a complaint’s or recovery’s details. With the current evidence that many service recovery attempts no longer unfold within a dyad via social media, research must expand its view as to who assesses justice perceptions. Moreover, the consumer types exposed to a complaint, recovery efforts, and other communications include the three aforementioned types of fellow consumers. A fourth type of fellow consumer can be added to this list: passive fellow consumers. This type includes all consumers who read and digest the communications during complaint and recovery efforts, yet do not actively post comments. Passive fellow consumers likely represent the largest group exposed to the details. In combination with the other fellow consumers, a single complainant’s justice perceptions pale in comparison to the sheer number of fellow consumers. In summary, all of the types of fellow consumers -- in addition to a complainant -- are likely to assess interactional and procedural justice perceptions associated with a firm’s social media recovery efforts. P2: a badvocate who participates in social media service encounters decreases A) a complainant’s and B) fellow consumers’ perceived interactional justice associated with a firm. P3: a badvocate who participates in social media service encounters decreases A) a complainant’s and B) fellow consumers’ perceived procedural justice associated with a firm. Peer Interactional Justice The traditional scope of interactional justice assesses the fairness of the treatment and communications between a complainant and a firm’s service representative. In the service recovery context, “interactional justice refers to the complainant’s level of satisfaction/dissatisfaction with the manner in 14 which the retailer [emphasis added] handled the complaint,” (Blodgett and Tax 1993, p. 101). Similarly, in the organizational justice context, interactional fairness is assessed between employees to account for, “fairness concerns raised about the propriety of the decision maker’s behavior [emphasis added] during the enactment of procedures,” (Bies and Shapiro 1987, p. 201). Moreover, interactional justice assesses the decision maker’s interactions in service recoveries or organizational issues of fairness, respectively. An important aspect of social media complaints compared to traditional complaints is the active participation of fellow consumers in what had previously been a two-party offline service encounter (i.e., a complainant and firm’s representative). The inclusion of fellow consumers, especially badvocates who exhibit interactionally unjust treatment, creates multiple sources of communication. Under the perspective of multifoci justice (Cropanzano et al. 2001), it is necessary to consider the source of injustice when assessing the fairness of a situation. The multifoci approach posits that people exist within complex social networks that create a myriad of sources to assess fair behavior. If judging interactional justice in general, without specifying a particular party or source of an interaction, an important piece of understanding the overall justice perception is missing (Rupp et al. 2014). Interestingly, the importance of separating closely related, yet distinct constructs to gain an accurate understanding of perceived justice is the primary reason why interactional justice was found to be distinct from procedural justice (Folger and Cropanzano 1998). The distinction between closely related justice constructs is needed because, “they might implicate blame in different fashions and perhaps to different degrees,” (Folger and Cropanzano 1998, p. 37). We posit that the fairness assessment of consumer interactions, none of whom are a firm’s decision maker, introduces the need to recognize an added dimension of perceived justice. The authors introduce peer interactional justice to represent the fairness of the interactions, communications, and treatment of a consumer by fellow consumers during a service encounter. This definition captures the essence of the existing interactional justice construct, but with the “source” of the focal unit of analysis shifting from a service representative’s interactions to a fellow consumer’s interactions. 15 The position of a consumer acting as a source of justice perceptions in a service recovery context can draw support from an organizational context. Organizational research posits that an employee’s perception of interactional justice can use a poorly behaved consumer as the source of unfair treatment (Rupp and Spencer 2006). In the current context we argue that the assessment of a peer interactional justice construct to account for badvocates’ and other fellow consumers’ interactions with a complainant is necessary to gain a clearer understanding of the overall perceived justice in online service recoveries. Peer interactional justice is necessitated by fellow consumers participating in the conversations during social media service encounters, a phenomenon largely absent in offline dyadic encounters. P4: fellow consumers who participate in social media service encounters cause a distinct justice dimension to emerge. Peer interactional justice is the fairness of social interactions with fellow consumers as perceived by A) a complainant and B) fellow consumers. P5: a badvocate who participates in social media service encounters will negatively impact peer interactional justice. Peer interactional justice will decrease as perceived by A) a complainant and B) fellow consumers as a badvocate’s treatment and communications toward a complainant becomes more rude, uncivil, or unfair. Theoretical Implications Branded social media web pages now feature online service encounters where multiple consumers are participating. Among these active and participative consumers are brand advocates who, in some cases, are behaving badly when interjecting within complaint and recovery episodes via social media. This qualitative investigation produced insights to this paper’s research question: what challenges do badvocates introduce during service recovery opportunities via social media? The emergence of the badvocate role throws a theoretical monkey wrench into existing service recovery theory. The results support the view that existing service recovery philosophies must be expanded to account for the inclusion of fellow consumers, and especially badvocates, when assessing the fairness of complaint handling via firms’ social media pages. The dysfunctional component of the badvocate role provides a unique insight into a new challenge during service recoveries. No dysfunctional consumer research assesses the actions of these disruptive individuals during another consumer’s complaining and recovery episode. The lack of research may be due 16 to social norms dictating that another consumer seeking assistance for a problem should not be a target of rude or uncivil behavior. Yet, due to the anonymity of the Internet some fellow consumers are acting out in a dysfunctional manner in these service situations. To complicate matters further, the dysfunctional component of a badvocate is adjoined with the advocate component of defending or supporting the brand. The latter component contradicts dysfunctional consumer research, because now the problematic consumer is attempting to assist, support, or help the firm. Hence, one contribution of this research is the illustration of a challenging new role that offers some benefits and some detriments to firms. Another theoretical implication is that a complainant’s perceived interactional and procedural justice of a firm is no longer limited to the interactions with a firm’s service employee. This position adds a unique aspect when examining the traditional justice perception philosophy, in which, a complainant determines fairness based solely on the firm’s recovery efforts. It is possible that a complainant will attribute an unjust act by a fellow consumer to a firm under the domains of fairness theory (Folger and Cropanzano 2001) and attribution theory (Kelley and Michela 1980). Thus, fellow consumers, in particular a misbehaving badvocate, must be accounted for as potential service inhibitors during recovery efforts. In our results not a single of the badvocate posts was responded to or addressed by a firm in an effort to address uncivil language or apologize to a complainant. Moreover, badvocates were unmanaged, which calls into question the inattention of firms choosing to ignore such uncivil actions. An interesting theoretical comparison as to the potential injustice of ignoring badvocates is drawn from Bies and Shapiro’s (1987) analogy of a journal editor choosing to ignore a reviewer’s rude or sarcastic comments to an author. The author is likely to infer intentional injustice by the editor if said editor, when responding to the author, does not explain or fails to justify a reviewer’s rude or sarcastic comments (Bies and Shapiro 1987). Another theoretical implication is the possibility for a large number of fellow consumers to now assess justice of a service recovery attempt. This is a world of change that may cause marketers to reconsider the importance of the focal unit of analysis during recovery efforts. Dysfunctional consumers in 17 in-person service environments negatively affect fellow consumer bystanders who witness misbehaving acts (Reynolds and Harris 2009). These fellow consumers will attribute some blame toward the firm (Huang 2008). This suggests that fellow consumers who read uncivil comments from a badvocate during a complainant’s plea for help to a firm will form their own justice perceptions. With a single complainant and possibly hundreds or thousands of fellow consumers who are reading, watching, listening, or participating in these service exchanges, it calls into question which unit of analysis (a complainant or fellow consumers) is more important when considering the sheer number of fellow consumers versus a single complainant. Another theoretical implication is the suggestion of an additional perceived justice dimension. Peer interactional justice is a byproduct of the evolution of technology and social media making it possible for online service encounters to occur. This evolution creates a service environment with different role players compared to the traditional dyadic environment. The suggestion of a new justice perception is consistent with the emergence of new constructs to extant models when moving from offline service situations to online service situations (e.g., service quality versus e-service quality; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Malhotra 2005). Service recoveries taking place in view of a large and participatory audience of fellow consumers will no doubt create communication exchanges between consumers. There should be little concern over norm adhering consumer-to-consumer communications on a brand’s social media page. However, problems are likely to arise when consumer-to-consumer communications violate commonly accepted social norms, such as the exchanges from badvocates. The three traditional dimensions of perceived justice in a service context assess the noticeable aspects occurring in a complaint handling process (Smith, Bolton, and Wagner 1999). Interactional, procedural, and distributive justice account for a complainant voicing a complaint, the corresponding treatment from a firm, the conflict resolution and policies, and the resulting outcome, respectively. When moving to social media recovery episodes, the badvocate introduces an additional aspect in a complaint handling process that is noticeable: norm violating communications. As if rude or uncivil comments were not noticeable enough, complainants who experience a failure and seek assistance have heightened 18 expectations of fair interpersonal treatment (Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran 1998), which suggests a badvocate’s response will be an easily noticeable aspect during a recovery encounter. Therefore, in a similar effort of prior service recovery research, the inclusion of a new construct to help assess a noticeable act during a recovery is warranted. Peer interactional justice may offer insight into how consumers process different exchanges and how they assign blame, separately or jointly, to a badvocate or firm. Future research should determine the positive versus negative value of a badvocate. This role has a mixture of positive and negative actions which require a deeper understanding. The suggestion of peer interactional justice is a ripe area of future research, such as developing a new construct, followed by the assessment of the shared and unique variance with the existing three justice dimensions. The relative weight of this new dimension compared to the weights of existing justice dimensions on endogenous constructs associated with a recovery, such as satisfaction with the complaint handling effort, is worthy of investigation. Evaluating if peer interactional justice has a direct effect on other justice dimensions, a direct effect on other endogenous constructs, or plays the role of a mediator or moderator between existing justice dimensions and other endogenous constructs are exciting areas of further research. Finally, a belief in some circles is that distributive justice may be the most important justice dimension. Future research may challenge this position, as the changing composition of the service dyad via social media causes fellow consumers to more easily discern peer interactional, interactional, and procedural justice dimensions. References Andersson, Lynne M. and Christine M. Pearson (1999), "Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace," The Academy of Management Review, 24 (3), 452-471. Bendapudi, Neeli and Leonard L. Berry (1997), "Customers' motivations for maintaining relationships with service providers," Journal of Retailing, 73 (1), 15-37. Berry, Leonard L. and Kathleen Seiders (2008), "Serving unfair customers," Business Horizons, 51 (1), 29– 37. Bettencourt, Lance A. (1997), "Customer voluntary performance: customers as partners in service delivery," Journal of Retailing, 73 (3), 383-406. Bhattacharya, C. B. and Sankar Sen (2003), "Consumer-Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers' Relationships with Companies," Journal of Marketing, 67 (2), 76-88. 19 Bies, Robert J. and J.F. Moag (1986), “Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness,” in Research in negotiations in organizations, Vol. 1, R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, and M. H. Bazerman, eds. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 43–55. ----- and Debra L. Shapiro (1987), "Interactional Fairness Judgments: The Influence of Causal Accounts," Social Justice Research, 1, 199-218. Bitner, Mary Jo (1990), "Evaluating Service Encounters: The Effects of Physical Surroundings and Employee Responses," Journal of Marketing, 54 (2), 69-82. -----, William T. Faranda, Amy R. Hubbert, and Valarie A. Zeithaml (1997), "Customer contributions and roles in service delivery," International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8 (3), 193-205. -----, Bernard H. Booms, and Lois A. Mohr (1994), "Critical Service Encounters: The Employee's Viewpoint," Journal of Marketing, 58 (4), 95-106. -----, -----, and Mary Stanfield Tetreault (1990), "The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favorable and Unfavorable Incidents," Journal of Marketing, 54 (January), 71-84. Blodgett, Jeffrey G. and Stephen S. Tax (1993),"The Effects of Distributive and Interactional Justice on Complainants Repatronage Intentions and Negative Word of Mouth Intentions," Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior 6 (1), 100-110. -----, Donald H. Granbois, and Rockney G. Walters (1993), "The Effects of Perceived Justice on Complainants' Negative Word of Mouth Behavior and Repatronage Intentions," Journal of Retailing, 69 (4), 399-428. -----, Donna J. Hill, and Stephen S. Tax (1997), "The effects of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice on postcomplaint behavior," Journal of Retailing, 73 (2), 185-210. Brown, Stephen, Robert V. Kozinets, and John F. Sherry Jr. (2003), "Teaching Old Brands New Tricks: Retro Branding and the Revival of Brand Meaning," Journal of Marketing, 67 (3), 19-33. Caza, Brianna Barker and Lilia M. Cortina (2007), "From Insult to Injury: Explaining the Impact of Incivility," Basic and Applied Psychology, 29 (4), 335-350. Chaudhuri, Arjun and Morris B. Holbrook (2001), "The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty," Journal of Marketing, 65 (2), 81-93. Chen, Hong-Mei and Stephen L. Vargo (2008), "Towards an alternative logic for electronic customer relationship management," International Journal of Business Environment, 2 (2), 116-132. Christopherson, Kimberly M. (2007), "The positive and negative implications of anonymity in Internet social interactions: 'On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog'," Computers in Human Behavior, 23 (6), 3,038-3,056. Cortina, Lilia M., Vicki J. Magley, Jill Hunter Williams, and Regina Day Langhout (2001), "Incivility in the Workplace: Incidence and Impact," Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6 (1), 64-80. Cropanzano, Russell, Zinta S. Byrne, D. Ramona Bobocel, and Deborah E. Rupp (2001), "Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice," Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58 (2), 164-209. 20 Day, Ralph L. and E. Laird Landon (1977), "Towards a Theory of Consumer Complaining Behavior," in Consumer and Industrial Buying Behavior. Arch Woodside. Jagdish Sheth, and Peter Bennett, eds. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. Deighton, John and Leora Kornfeld (2009), “Interactivity’s Unanticipated Consequences from Marketers and Marketing,” Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23 (1), 4-10. Dick, Alan S. and Kunal Basu (1994), "Customer Loyalty: Toward an Integrated Conceptual Framework," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22 (Winter), 99-113. Dwyer, Robert F., Paul H. Schurr, and Sejo Oh (1987), "Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships," Journal of Marketing, 51 (2), 11-27. Fisk, Ray, Stephen Grove, Lloyd Harris, Dominique A. Keeffe, Kate Daunt, Rebekah Russell-Bennett, and Jochen Wirtz (2010), "Customers behaving badly : a state of the art review, research agenda and implications for practitioners," Journal of Services Marketing, 24 (6), 417-429. Folger, Robert and Russell Cropanzano (1998), Organizational justice and human resource management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ----- and ----- (2001), “Fairness Theory: Justice as Accountability,” in Advances in Organizational Justice, J. Greenberg and R. Cropanzano, eds. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1-55. Fullerton, R.A. and G. Punj (2004), "Repercussions of promoting an ideology of consumption: consumer misbehavior," Journal of Business Research, 57 (11), 1239-1249. Gallaugher, John and Sam Ransbotham (2010), "Social Media and Customer Dialog Management at Starbucks," MIS Quarterly Executive, 9 (4), 197-212. Gelbrich, Katja and Holger Roschk (2011), "A Meta-Analysis of Organizational Complaint Handling and Customer Responses," Journal of Service Research, 14 (1), 24-43. Grönroos, Christian (1988), "Service Quality: The Six Criteria of Good Perceived Service Quality," Review of Business, 9 (Winter), 10-13. Grove, Stephen J. and Raymond P. Fisk (1997), "The Impact of Other Customers on Service Experiences: A Critical Incident Examination of 'Getting Along,"' Journal of Retailing, 73 (1), 63-85. Gruen, Thomas and Jeffery M. Ferguson (1994), “Using Membership as a Marketing Tool: Issues and Applications,” in Relationship Marketing: Theory, Methods and Applications. Jagdish N. Sheth and Atul Parvatoyar, eds. Atlanta: Center for Relationship Marketing, Roberto C. Goizueta Business School, Emory University, 60–64. Harris, Lloyd C. and Mark M. Goode (2004), "The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: a study of online service dynamics," Journal of Retailing, 80 (2), 139-158. ----- and Kate L. Reynolds (2003), “The Consequences of Dysfunctional Customer Behavior,” Journal of Service Research, 6 (2), 144–61. 21 Hart, Christopher W.L., James L. Heskett, and W. Earl Sasser Jr. (1990), "The Profitable Art of Service Recovery," Harvard Business Review, 68 (July/August), 148-56. Huang, Wen-Hsien (2008), "The impact of other-customer failure on service satisfaction," International Journal of Service Industry Management, 19 (4), 521-536. Kahneman, Daniel and Dale T. Miller (1986), "Norm Theory: Comparing Reality to Its Alternatives," Psychological Review, 93 (2), 136-153. Kelley, Harold H. and John L. Michela (1980), "Attribution Theory and Research," Annual Review of Psychology, 31 (1), 457-501. Kozinets, Robert V. (1998), "On Netnography: Initial Reflections on Consumer Research Investigations of Cyberculture," in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 25. Joseph Alba and Wesley Hutchinson, eds. Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 366-71. ----- (1999), "E-Tribalized Marketing? The Strategic Implications of Virtual Communities of Consumption," European Management Journal, 17 (3), 252-64. ----- (2002), "The Field behind the Screen: Using Netnography for Marketing Research in Online Communities," Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (1), 61-72. ----- and Jay M. Handelman (2004), "Adversaries of Consumption: Consumer Movements, Activism, and Ideology," Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (3), 691-704. Lovelock, Christopher H. (1994), Product Plus: How Product and Service Equals Competitive Advantage. New York: McGraw-Hill. Luckerson, Victor (2013), “Man Spends More Than $1,000 to Call Out British Airways on Twitter,” accessed May 1, 2014 (available at http://business.time.com/2013/09/03/man-spends-more-than1000-to-call-out-british-airways-on-twitter). Macneil, Ian R. (1978), "Contracts: Adjustment of Long-Term Economic Relations Under Classical, Neoclassical and Relational Contract Law," Northwestern University Law Review, 72, 854-902. ----- (1980), The New Social Contract, An Inquiry into Modern Contractual Relations. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Oliver, Richard L. (1999), "Whence Consumer Loyalty?," Journal of Marketing, 63 (Special Issue), 33-44. Osgood, D. Wayne, Lloyd D. Johnston, Patrick M. O'Malley and Jerald G. Bachman (1988), "The Generality of Deviance in Late Adolescence and Early Adulthood," American Sociological Review, 53 (1), 81-93. Pan, Yue and Jason Q. Zhang (2011), "Born Unequal: A Study of the Helpfulness of User-Generated Product Reviews," Journal of Retailing, 87 (4), 598-612. Parasuraman, Ananthanarayanan, Valarie A. Zeithaml, and Arvind Malhotra (2005) "ES-QUAL a multipleitem scale for assessing electronic service quality," Journal of Service Research, 7 (3), 213-233. Pedersen, Darhl M. (1997), "Psychological Functions of Privacy," Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17 (1), 147-156. 22 Phillips, Tim and Philip Smith (2003), "Everyday incivility: towards a benchmark," The Sociological Review, 51 (1), 85-108. ----- and ----- (2004), "Emotional and behavioural responses to everyday incivility," Journal of Sociology, 40 (4), 378-399. Reynolds, Kate L. and Lloyd C. Harris (2009), "Dysfunctional Customer Behavior Severity: An Empirical Examination," Journal of Retailing, 85 (3), 321-335. Rosenbaum, Mark S. and Carolyn A. Massiah (2007), "When customers receive support from other customers: exploring the influence of intercustomer social support on customer voluntary performance," Journal of Service Research, 9 (3), 257-270. Rupp, Deborah E. and Sharmin Spencer (2006), "When Customers Lash Out: The Effects of Customer Interactional Injustice on Emotional Labor and the Mediating Role of Discrete Emotions," Journal of Applied Psychology, 91 (4), 971-978. -----, Ruodan Shao, Kisha S. Jones, and Hui Liao (2014), "The utility of a multifoci approach to the study of organizational justice: A meta-analytic investigation into the consideration of normative rules, moral accountability, bandwidth-fidelity, and social exchange," Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123 (2), 159-185. Smith, Amy K., Ruth N. Bolton, and Janet Wagner (1999), "A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery," Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (3), 356-372. Smith, Shaun and Joe Wheeler (2002), Managing the Customer Experience: Turning Customers into Advocates. London: Pearson FT Press. Solomon, Michael R., Carol Surprenant, John A. Czepiel, and Evelyn G. Gutman (1985), "A Role Theory Perspective on Dyadic Interactions: The Service Encounter," Journal of Marketing, 49 (1), 99-111. Strauss, Anselm and Juliet Corbin (1998), Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Sun, Tao, Seounmi Youn, Guohua Wu, and Mana Kuntaraporn (2006), “Online word-of-mouth (or mouse): An exploration of its antecedents and consequences,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11 (4), article 11. Tax, Stephen S., Stephen W. Brown, and Murali Chandrashekaran (1998), "Customer Evaluations of Service Complaint Experiences: Implications for Relationship Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 62 (April), 60-76. Thibaut, John and Laurens Walker (1975), Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Zimbardo, Philip G. (1969), “The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order vs. deindividuation, impulse, and chaos,” in Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. 17), W. J. Arnold & D. Levine, eds. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 237–307. 23 Table 1 – A Typology of Consumers Panel A: Various Consumer Types Within Marketing Consumer Type Behavior/Role Performed Transitions to Type Relevant Literature Non-Customer or Customer Æ Dysfunctional behavior Æ Dysfunctional Consumer Fisk et al. 2010; Harris and Reynolds 2003; Reynolds and Harris 2009 Non-Customer Æ First-time purchase or infrequent purchases Æ Non-Loyal Customer Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Macneil 1978; 1980 Non-Loyal Customer Æ Repeated purchases Æ Loyal Customer Dick and Basu 1994; Harris and Goode 2004; Oliver 1999 Loyal Customer Æ Positive extra-role behavior Æ Brand Advocate Bendapudi and Berry 1997; Bettencourt 1997; Chen and Vargo 2008 Panel B: 1 The Desirability of Various Types of Consumers from a Firm’s Perspective Low Noncustomer Dysfunctional Consumer Non-Loyal Customer Loyal Customer Brand Advocate High Desirability from a Firm’s Perspective 1 The consumer typology in Panel B is not meant to be all-inclusive for every possible type of consumer. These consumer types best represent the focal concepts under investigation. Other types of consumers exist, such as satisfied consumers, co-producing consumers, and other types who perform different roles. The marketing literature is vast and involves many additional consumer variables and concepts that are considered beyond the scope of this research. 24 Table 2 – Type of Consumer Message Threads via Brands’ Social Media Pages Retailer Service Threads: Complaint and Recovery Opportunity General Question / Support 2012 267 (55%) 114 (24%) 153 (32%) 2013 367 (66%) 178 (32%) 189 (34%) 2-Year Total 634 (61%) 292 (28%) 342 (33%) Non-Service Threads: Compliments/Positive Content Toward Brand Sharing news / links Miscellaneous / other comments General questions toward other consumers 214 (45%) 175 (36%) 14 (3%) 15 (3%) 10 (2%) 185 (34%) 135 (25%) 35 (6%) 6 (1%) 9 (2%) 399 (39%) 310 (30%) 49 (5%) 21 (2%) 19 (2%) Retailer Total Message Threads 481 552 1,033 Service Threads: Complaint and Recovery Opportunity General Question / Support 2012 91 (38%) 71 (30%) 20 (8%) 2013 97 (60%) 78 (48%) 19 (12%) 2-Year Total 188 (47%) 149 (37%) 39 (10%) Non-Service Threads: Compliments/Positive Content Toward Brand Sharing news / links Miscellaneous / other comments General questions toward other consumers 148 (62%) 116 (49%) 2 (>1%) 29 (12%) 1 (>1%) 65 (40%) 34 (21%) 23 (14%) 7 (4%) 1 (>1%) 213 (53%) 150 (37%) 25 (6%) 36 (9%) 2 (>1%) Hotel Total Message Threads 239 162 401 Hotel 25 Table 3 – Four examples of complaints responded to with uncivil responses from fellow consumers who actively sided with the brand Complaint Thread One: Dora: “(Retailer’s name) apparently when there is a spill we just throw down whole rolls of paper towels and a yellow cone and just walk away… wow… [a picture of a large spill in the store’s aisle way was also posted] Retailer: “Dora, at which store was this?” Dora: “This is the store at (address given)… it was a good thing that I was paying attention to where I was walking otherwise there could have been a huge problem.” Frank: “Quit crying. You could have got your ass down on all fours and cleaned it up…” Dora: “Well I’m not an employee of the store and I’m 6.5 months pregnant…” Frank: “What a big baby” Complaint Thread Two: Rob: “How incredibly amazing that I just checked your website for room rates when things are back to normal in New York. And instead of the $515 you jerks charged me for a regular room on a Wednesday and Thursday. Somehow, a king suite for a Wednesday and Thursday is only $479 per night. Price gouging jerks. Hope you get bed bugs.” Hotel: “Rob, we’d like to speak with you to resolve any issues you have had. Please message us your contact information and we will have customer service reach out to you. Thank you.” Jan: “You people are so incredibly incompetent. 1. If you want to know the maximum amount a hotel can charge nightly BY LAW, look at the information sheet on the back of your entry door to the guest room. 2. Hotel rates are based on supply and demand. Obviously the demand was very high. The rate goes up… I would like to think (wishful thinking) you people are smart but I still can’t come to understand how you can act so stupid on social media.” Complaint Thread Three: Ed: “So tired of going to (Retailer’s name) to buy Diet Mountain Dew, only to find the shelf like this. Had the same problem with a brand of potato chips. Store staff always blames “the Pepsi driver” or “the Frito Lay driver”. It’s YOUR store. Take responsibility for keeping YOUR customers happy… [a picture of the empty store shelf was also posted] Retailer: Thank you for the feedback, Ed. At which store was this? We will share this with the vendor responsible for stocking this area.” Bill: “Ed, YOU are out of line. These items are controlled by Pepsi, if anything go complain on Pepsi’s facebook page. Don’t be an idiot.” Complaint Thread Four: Mel: “I’m completely disgusted by the lack of respect and poor customer service I experienced this past week with (retailer’s name). I purchased Sunny D that was on sale, gave it to my son, then discovered it expired in August… [a picture of the bottle’s UPC and the receipt was also posted] Sam: “the UPC on the Sunny D is the same on every bottle unless it’s a different flavor… so the UPC on a receipt does not prove anything… This would be hard to prove that it was on the shelf, and I myself don’t believe it… more like in someone’s pantry since the last sale… good try though.” 26