The Vulnerability of Love - First Presbyterian Church

advertisement

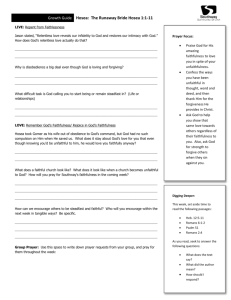

“The Vulnerability of Love” By Rev. Joseph J. Clifford, D. Min. Text: Hosea 11:1‐9 First Presbyterian Church of Dallas November 15, 2015 “There is but one only living and true God, who is infinite in being and perfection, a most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts, or passions.” So begins Chapter 2 of the Westminster Confession, written in the 1640’s by English puritans and Presbyterians—our forefathers in faith. I remember reading that in seminary and wondering how the Westminster Divines came to the conclusion that God is without passion. Every phrase of the Westminster Confession has a Biblical text to prove its truth—we Presbyterians invented proof‐texting. To justify the statement that God is without passion, the Westminster Divines cited Acts 14:11, when Paul says to the Lyceans who mistake him for Zeus, “Sirs, why do ye say these things? We also are men of like passions with you.” Since human beings have passion, apparently the Westminster Divines concluded God is without passion. Hosea would have disagreed with them. Hosea was a prophet in the Northern kingdom in the 8th century BCE, contemporary to Amos. His ministry was during the last chaotic decades of the Northern kingdom, when Israel lived in conflict with Judah and under constant threat of Assyrian invasion. Such chaos created a game of thrones – four kings were assassinated in the last 25 years before the Northern kingdom was conquered by the Assyrian empire. Suffice to say it was a time of great vulnerability for Israel. In their vulnerability they reached out to false gods, to Baal and the idols of their culture, to political alliances with countries like Egypt to assure their future. Here’s how Hosea puts it in chapter 4: Hear the word of the Lord, O people of Israel; for the Lord has an indictment against the inhabitants of the land. There is no faithfulness or loyalty, and no knowledge of God in the land. Swearing, lying, and murder, and stealing and adultery break out; bloodshed follows bloodshed. …My people consult a piece of wood, and their divining rod gives them oracles. ..They sacrifice on the tops of the mountains, and make offerings upon the hills…Like a stubborn heifer, Israel is stubborn; can the Lord now feed them like a lamb in a broad pasture? Ephraim is joined to idols— let him alone. More than any other prophet, Hosea reveals how this idolatry breaks God’s heart. The God of Hosea is filled with deep passion. No passage within Hosea reflects this reality more than Hosea 11. Walter Brueggemann names this passage as, "among the most remarkable oracles in the entire prophetic literature." H. D. Beeby, writes that in Hosea 11, “we penetrate deeper into the heart and mind of God than anywhere in the Old Testament."1 And what do we find in the heart of God, and on the lips of Hosea? Love. In fact, Biblical scholar Bruce Birch says that 1 Cited by J. Clinton McCann in his article for www.WorkingPreacher.org. Can be found here: http://www.workingpreacher.org/preaching.aspx?commentary_id=643&show_mobile=true 1 this text is the first one to base God’s relationships to the people on love.2 Together let us listen for God’s word to us from the words of Hosea 11: Hosea 11:1‐9 11When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son. 2The more I called them, the more they went from me; they kept sacrificing to the Baals, and offering incense to idols. 3Yet it was I who taught Ephraim to walk, I took them up in my arms; but they did not know that I healed them. 4I led them with cords of human kindness, with bands of love. I was to them like those who lift infants to their cheeks. I bent down to them and fed them. 5They shall return to the land of Egypt, and Assyria shall be their king, because they have refused to return to me. 6The sword rages in their cities, it consumes their oracle‐priests, and devours because of their schemes. 7My people are bent on turning away from me. To the Most High they call, but he does not raise them up at all. 8 How can I give you up, Ephraim? How can I hand you over, O Israel? How can I make you like Admah? How can I treat you like Zeboiim? My heart recoils within me; my compassion grows warm and tender. 9I will not execute my fierce anger; I will not again destroy Ephraim; for I am God and no mortal, the Holy One in your midst, and I will not come in wrath. “I led them with cords of human kindness, with bands of love …lifting them to my cheek like a baby. …How can I give you up? How can I hand you over?” What passion; what pathos. How could anyone come to the conclusion God is without passion after reading Hosea 11? Imagine how radical it was for a prophet speaking over 2,700 years ago about this passionate love of God for God’s people. There’s was a world where the gods were capricious at best, terribly destructive at worst. The gods of Canaanite fertility religions, the gods of the Assyrians and the Egyptians, they treated human beings like pawns in a game for their own delight, but Hosea declares the one true God to be more like a broken hearted lover in the early chapters, or a frustrated parent in today’s passage. Israel is like a recalcitrant teenager. God is like the raging parent shouting, “I brought you into this world, I can take you out.” And yet God cannot let Ephraim go. I’ve shared with you before a story from United Methodist Bishop Will Willimon.3 At a church fellowship gathering one night, Willimon saw a woman he knew and posed the courteous not‐really‐looking for an answer question, “How are you doing?” She replied, “Not so well. The past six months have been a living hell.” He was hooked, so he asked, “What’s happening?” “Well,” she said, “our 2 Birch, Bruce. Westminster Bible Companion: Hosea, Joel, and Amos. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1997,) p. 99. 3 William Willimon. “How Jesus Saves,” from the lectures delivered at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary’s Mid Winter lecture entitled, “Jesus Saves. Delivered February 4, 2008. 2 eighteen year old son disappeared six months ago, we haven’t known where he was. He just left in a rage. He’s 18, what are we going to do? “The other night, my husband and I were eating dinner when we heard a banging on the front door. There was a lot of yelling and cursing, so I had a feeling who it was. I went and opened the door, and he burst in yelling some obscenity at me, storming through the kitchen and into his bedroom where he slammed the door shut. I heard the lock click. ‘Want some supper?’ I said. ‘Blank off,’ he yelled back. “My husband poured a drink and went into the family room to watch TV. That’s what he does. I don’t know what came over me. I went into the garage and found my husband’s hammer. It was one of those big hammers, a really big hammer—a sledge hammer. I went to our son’s room and said, ‘Let me in.’ He yelled some more obscenities back at me. So I took that hammer, and swung it at the door. One hit split the door in two. I broke through what was left of the door to see my son standing in the middle of the room, terrified. I caught him up under the chin and pushed him back against the wall and said, ‘I went through labor because of you … and I’m not going to let you go.” Willimon ended the lecture, “I think God’s like that.” Hosea would agree. Such love is a radical proposal, because the moment God chooses to love, God becomes vulnerable, vulnerable to rejection. That’s exactly what has happened to God in Hosea. God has been rejected and God is heart broken. Human beings know the pain of heartbreak. Dr. Brene Brown is a research professor at the University of Houston. She became famous because of her Ted Talk entitled, “The Power of Vulnerability.”4 With over 22 million views, it’s one of the five most watched Ted Talks in history. Her research began by looking into the nature of connection. She discovered human beings are made for connection. It is why we exist. Brown says, “It’s what gives purpose and meaning to our lives…(T)he ability to feel connected is why we’re here…neurobiologically that’s how we’re wired.”5 Perhaps that’s because we’re made in the image of God? Some might say, “we’re made for each other.” As she began her research on connection, particularly on love, she discovered, “when you ask people about love, they tell you about heartbreak. When you ask people about belonging, they’ll tell you their most excruciating experiences of begin excluded. When you ask people about connection, the stories they tell (sic) are about disconnection.” She determined that the thing that led people to name their disconnections and exclusions and heartbreak was shame— fear of disconnection. As I listened to her Ted Talk, I thought about all the shame of Hosea, about his marriage to an unfaithful wife in the beginning of the book, about the shame of a jilted lover, the shame of a parent whose child runs wild. It leaves God vulnerable. It leaves God heart broken. In her research, Brown discovered a common trait of people who thrive in life and relationships is “courage.” She’s not talking about a macho sense of bravery. The Latin root of courage is 4 5 See: http://www.ted.com/talks/brene_brown_on_vulnerability Ibid., at the 3:08 mark. 3 “cor,” meaning “heart.” For Brown, to have courage means to have heart, to be “whole‐ hearted.” Such courage leads to a willingness to be vulnerable. In describing people with such courage, Brown says, “They were willing to invest in a relationship that may or may not work out…(they are willing) to breathe through waiting for the doctor to call after the mammorgram…they (are willing) to say, ‘I love you’ first.”6 According to Hosea, God is like that too. God is whole‐hearted. God is willing to say, “I love you” first, to be vulnerable to rejection and heartbreak. How do we respond? How do we respond to this vulnerability of God? How do we respond to the fact that we are vulnerable as human beings, vulnerable to rejection, to pain, to exclusion, to death? One way people respond is to become comfortably numb. As Brown points out, we are the most in‐debt, obese, addicted and medicated adult cohort in US History. We don’t want to deal with vulnerability, grief, fear, disappointment, so we have a couple of beers, or glasses of Chardonnay, or my personal favorite, a pepperoni pizza… and we try to become comfortably numb. The only problem is in the process we become numb to everything else—numb to joy, numb to gratitude, numb to happiness. And in our grief, we repeat the cycle over and over again. That’s one way to respond to vulnerability. It’s not a healthy way. Another is to make the uncertain of this world artificially certain. That’s what the ancient Israelites did. They turned to idolatry to find their certainty. Paul Tillich said this tendency of human beings to seek security in the material world was the root cause of idolatry. Brown declares, “Religion has gone from a belief in faith and mystery to certainty.” Indeed, when people become so certain about God, so certain about God’s will and God’s way, well they can justify anything in the name of their religion—even killing innocent people in a concert hall or a restaurant or a soccer game. Certainty is no antidote to our vulnerability. There’s another way to respond, another way to respond to the God who embraces the vulnerability of rejection by saying, “I love you” first. It’s to be willing to live with our own vulnerability. Brene Brown puts it this way, “To let ourselves be seen, deeply seen, vulnerably seen…to love with our whole hearts, even though there’s no guarantee.” I see this vulnerability in the painting on our bulletin this morning, Vincent Van Gogh’s “First Steps,” his interpretation of a painting originally created by the French artist, Millet. Van Gogh painted this when he was in an asylum in Saint Remy. I’ve always been amazed by the beauty of Van Gogh’s work, given how painful life was for him, how vulnerable he must have felt. Yet he created such beauty. 6 Ibid. 9:39 mark. 4 Looking at the parents, do you see their vulnerability? There’s the willingness of the mother to let her young child go, to risk letting go of that hand, letting her take that step, to risk failing, to risk watching her baby walk away. There’s the father, down on his knee reaching out in love, “Oh Ephraim, I taught you to walk…” According to Hosea, God is like that. And then there is the child. Is anything in this world more vulnerable than a baby learning to walk? And yet, what courage, what a willingness to risk, a willingness to fall, to fail, to take that uncertain step forward, and perhaps to discover freedom, to discover adventure, to discover joy that knows no bounds. If God can embrace such vulnerability as our parent, can we? Can we imagine the risk of loving one another in such a way? Can we imagine taking the risk to say, “I love you” first? Can we imagine risking reaching out to the other, knowing we may be wounded in the process? Can we imagine refusing to live in fear of the other in our own community or in the wider world? Can we imagine not letting the rage we feel toward those cowards who murdered so many innocent people on the streets of Paris define our response to the tragedy, nor to refugees seeking asylum, nor to people who are Muslim? If God can be that vulnerable, can we? 5