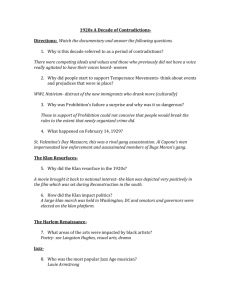

Sequence of events on Nov. 3, 1979

advertisement