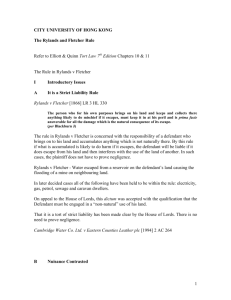

29 U. D

advertisement