File

advertisement

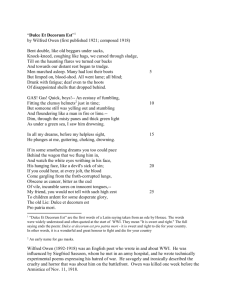

Dulce et Decorum Est 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock –kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs, And toward our distant rest began to trudge. Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots, But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind: Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots Of gas-shells dropping softly behind. 9 10 11 12 13 14 Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! --- An ecstasy of fumbling, Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time, But someone still was yelling out and stumbling And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime. --Dim through the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. 15 16 In all my dreams before my helpless sight He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning. 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace Behind the wagon we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin, If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, --My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori. Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) 1. Vocabulary: Important or Unknown words Beggars: poor, ragged people who seek help from others Knock –kneed: a gait characterized by striking the knees together Hags: old, ugly, decrepit women Haunting: evoking strong emotion, especially a sense of sadness, that persists for a long time Trudge: to walk with slow, heavy, weary steps -shod: past tense of shoe lame: hobbled, restrained, injured ecstasy: a feeling or activity characterized by extreme intensity stumbling: to trip when walking or running flound’ring: to make clumsy uncontrolled movement while trying to regain balance or move forward drowning: to die; or kill a person through suffocation by immersion in liquid, usually water. plunges: to move, rush, dive, or be thrown suddenly downward or forward; guttering: choking: to stop breathing, or breathe with great difficulty, because of a blockage or restriction of the throat smother: to deprive somebody or something of air, or to be deprived of air; to kill somebody or something, or to die by suffocation flung: (past tense of fling) to throw something or somebody fast using a lot of force writhe(ing): to make violent twisting and rolling movements with the body, especially as a result of sever pain; to move in a twisting, squirming way. sin: an act, or thought, or behavior that goes against law or teachings of a particular religion, especially when the person who commits it is aware of this. corrupt(ed): extremely immoral or depraved; contaminated or tainted by something else. cud: partly digested food that cows and other ruminants return to the mouth, after it has passed into the first stomach, to chew again as an aid to digestion vile: 1. causing disgust or abhorrence 2. very evil or shameful 3. extremely unpleasant to experience 4. of little or no worth (archaic) 5. so despicable or undesirable as to be degrading sore: a painful open skin infection or wound innocent: pure and uncorrupted by evil , sin, or experience of the world zest: to make an experience more enjoyable by adding excitement or interest to it. ardent: feeling or showing great enthusiasm or eagerness desperate: so drastic or reckless as to be suitable only for a last resort glory: something that brings or confers admiration, praise, honor, or fame. lie: a false statement made deliberately; false impression created deliberately (definitions taken from Encarta World English Dictionary) 2) Does the poet use imagery? Is there one dominant image? Yes. Owen places the reader on the battlefield at night where a gas attack kills a fellow soldier. Does the author use multiple images? Yes. Owen starts with a column of men returning from the front utterly exhausted. He follows this with soldiers scurrying to protect themselves from the gas. The last two images show a man convulsing in the throws of chemical death, and the narrator’s march behind the wagon where his comrade lies dead, and visible. Owen also alludes to a symbolic sickness: “Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues” where the youth of his time have had their voices destroyed with the advent of war. How do the images relate to each other? (thematically /visually/chronologically) These three images connect in all three ways. Firstly, the poem works as a Narrative Poem: it tells a chronological story of men under attack. Secondly, they connect visually because each shows a battlefield event. Lastly, the images thematically depict awful tragedy, as well as the haunting effects of gruesome death on the psyche where the narrator describes his ongoing nightmare in which he sees his comrade “plunge[s] at me, guttering, choking, drowning.” Do the images appeal to one sense more than another? The images appeal visually with such words and phrases as: bent double beggars limping, coughing hags haunting flares blood-shod feet men “drunk” with fatigue a man “drowning” in a “green sea” of gas the choking friend in his dreams his dead comrade with the “white eyes writhing” and the ‘hanging face” “innocent tongues” filled by “incurable” “vile” “sores”. Sound Imagery also punctuates this poem with such words as: “coughing…cursed… hoots of gas-shells dropping softly…Gas! GAS! Quick boys! (dialogue)…guttering…choking…gargling.” Each of these auditory images enhances the battlefield and nightmare images with the horrific sounds of weapons exploding and the human carnage that follows. 3) What other poetic devices does the author employ? Simile? Owen uses similes in many of his images. He compares the soldiers to “old hags…bent double…under sacks”, and as “hags…(who)trudge knock-kneed (and) coughing like hags.” When the gas arrives and one man succumbs, Owen describes his ghastly death from the perspective of a man who peers through the “misty panes” of an undersea helmet and “thick green light, as under a green sea” where he helplessly watches the man “drowning” in his own fluids accumulating in his lungs. Once his comrade succumbs, Owen compares the poor wretch’s face to that of a “devil’s sick of sin.” Metaphor? Owen, in his final lines, has the narrator tell the audience that “the old Lie: Dulce et decorum est/ pro patria mori” is a “vile, incurable sore on (the) innocent tongues” of young men who run off to war. Personification: None Sound Imagery (onomatopoeia / assonance / consonance / alliteration etc..) Owen only describes the sounds the men would hear, and does not use onomatopoeia to present them. There does not appear any deliberate at rhyme and meter nor sound imagery of assonance/ consonance or alliteration in repeated, predictable ways. Owen does, however, use consonance to good effect when the narrator tell us about “backs…toward…distant…rest…trudge”; “all…went lame, all blind“…clumsy helmets”; “misty panes”; “just…time”; “his face”; Irony of setting / action / or word? The last two lines, “The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est/Pro patria mori form the basis for the irony in the poem: the entire setting is a dreadful, muddy, ghastly escarpment of walking dead. How could their end be glorious? How could drowning in your own fluids present a chivalrous way to end ones life? The bitter tone of, “The Old Lie:” enables the reader to hear Owen’s biting anger at the loss of his friends’ lives as well as his own innocence. Juxtaposition: none 4) How does the poem convey emotion or opinion to the reader? What mood does each image project? a. The images in the first eight lines convey a mood of desolation, resignation, and acceptance of death. The men cannot see, cannot feel, and march as dumb animals away from the slaughter, yet the gas finds them and kills them. b. The mood in the images found in lines nine through fourteen depict wild and thoughtless action. The men merely react to preserve their lives, without thinking, knowing instinctively that they will die a gruesome death if they do not act swiftly enough. Drowning through suffocation leaves the reader trapped, too, like the poor soldier who succumbs to the gas. c. Lines fifteen and sixteen take on the quality of the nightmare they are for the narrator- he is helpless before his dreams, as his subconscious torments him when he tries to sleep and put away the visions of his daily life. d. Lines seventeen through twenty four leave me with the sickened feeling of watching a once living friend twitch and gargle his way to an unpreventable death just feet ahead in a wagon fit for carrying beasts. Owen’s description of this man as both innocent and now dieing with the face of a devil only compound the frustration I feel when reading this. How does the mood from the images cohere? Do they? All of these images cohere to present the horror and misery of fighting and dying in an unknown place for reasons that do not matter to a young man whose life has left him in such a grisly way. Who narrates the poem and how? The narrator of the poem is a soldier who is walking in a column with the men when the attack occurs. He tells the poem in past tense and in a narrative way. At the third stanza, the tense shifts to present, thereby highlighting the ongoing nightmares the narrator still suffers. By the last stanza, the narrator speaks directly to the audience, when he uses the words, “If in some smothering dreams you too could pace…If you could hear …My friend, you would not tell…” The narrative structure starts, then with a telling of a story to a direct and pointed appeal to the reader that he cannot speak words of bravado with any authority until he has seen the horrors of war firsthand. 5) What is the author’s tone? What is the author’s point of view about the subject(s) of the poem? The author clearly pities the men he fights with when he describes them using animal imagery (blood-shod), their helpless state (“lame…blind…deaf). His description of the man’s death does not embody any of the conventions of chivalric valor: no charging the lines of the enemy screaming a bloodcurdling battle cry, no yells for Queen and country-just a young man who flounders as if on fire, which he is, internally. The last two lines of the poem hammer home Owen’s loss of innocence and his anger with the propaganda he has endured. His capitalization of the word “lie” only further states his case: the notion of dying for ones country has grown to an institutional level. Which images/figurative language/vocabulary inform your opinion: all of the ones listed above 6) What aspects of the author’s life inform the tone of this poem? What life events, readings, religious background, or political points of view have shaded how the author perceives ideas embedded in the poem? Owen had volunteered for the war and entered by 1917 after a prolonged training. He had supported the war while a civilian in England, publishing at least one poem that invoked the beauty of dying with ones comrades on the field of battle. Owen had training in the classics and had spent time as a tutor of English prior to his enlistment. As a young boy, he held a great religious fervor, and for some time had believed that he would enter the clergy. Both of these pursuits added to his work: he had strong grounding in the conventions of poetry and writing, and his sense of moral outrage grew from his personal belief in the greater good of mankind. He had written to his sister, “War was a hideous, unchristian business, and the churchmen who were trying to pretend otherwise were lying” (Hibberd 249). As a young schoolboy in England, one schooled in the classics, he had accepted without question the glory of “closing with the enemy” and testing one’s physical and moral courage in combat. Classical literature ran rife with swords and banners and gilt glistening. World War I proved muddy, ugly, and utterly senseless from a tactical point when Owen entered the war. th On the night of April 6 , 1917 while Owen’s Manchester regiment trudged back from the front, they “were overtaken by gas, the incident described in ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ when one man, too slow with his helmet, chokes to death” (Hibberd 235). As a result of his combat, Owen was diagnosed with “Shell Shock” and sent to Craig Lockharte for treatment. There, “Wilfred’s worst symptom was violent dreams. His earlier ‘phantasms’, visions of ‘bloodiness and stains of shadowy crimes’, came back in a wartime guise, infinitely more dreadful than before. Worst of all were the faces, among them those of the gassed man…like many of the other patients, Wilfred must often have woken screaming in the night” (Hibberd 246). Owen, like many of the men of his time, held a romantic view of warfare. The poetry that he crafted during his time in the asylum of Craig Lockharte, reflected the terror, horror, and endless slaughter where tens of thousands of men could lose their lives each day and lay rotting on the battlefield. Owen’s would find himself suffering from Shell Shock after lying in a shell crater for days with the body parts of his friend “Cockrobin.” At one point, after thirty-six hours of constant shelling, Owen considered allowing himself to slip into the collected water at the bottom and drown. He controlled that urge, but the death of “Cockrobin”, the constant shelling, and the witnessing of a friend shot while on duty (“The Sentry”) propelled Owen to reject warfare in general, and the Great War in particular. 7) Can the ideas expressed in this poem also find meaning in other contexts….. While not as severe as war, society has told us as youths that certain Truths exist. For instance, one belief forwarded remains the notion that when a person works hard enough, that very ethic will take care of all aspect of luck, race, religion, family background. Some in our society may find this Truth a Lie as they struggle with menial and meaningless work. Others Truths students have heard include the idea that college remains the key to success in our society. Those who have attended college, and have this perspective, may not always believe that the four or six or eight years spent studying have met the expectations of worth set by society. While these examples do not have the same mortality embedded in them that Owen’s perception of war, the notion of betrayal and bitterness, while confronting the reality of our existence, show some parallel.