Like a Marriage with a Monkey - University of Pittsburgh Press

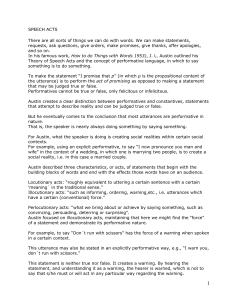

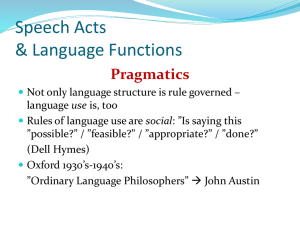

advertisement