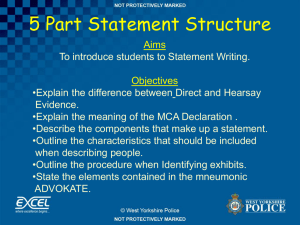

hearsay in civil and criminal cases

advertisement