Reinventing Humanitarian Intervention: Two Cheers for

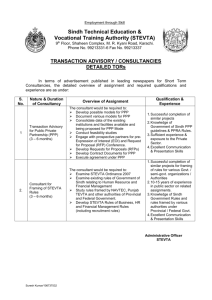

advertisement