The Figure in the Landscape: Capote and Infamous SOURCE

AUTHOR:

TITLE:

Phyllis Frus

The Figure in the Landscape: Capote and Infamous

SOURCE: Journal of Popular Film and Television 36 no2 52-60 Summ 2008

I was driving around the Great Plains looking at different things and I went to the Clutter house in Holcomb,

Kansas. It was kind of spooky walking around out there until I thought of Truman Capote out there on the plains, doing his reporting on their murder. This tiny figure in this landscape. And this big book he was carrying around. And I couldn't help thinking -- you know, if he had written that in as well -- himself, small, running round -- who knows, his entire book might've been different. - - Ian Frazier, quoted. in Hilton Als's Village Voice review of Great Plains

In Cold Blood is a nonfiction account, narrated in the style of a novel, of the killings of four members of the Clutter family in a farmhouse in Kansas in 1959; the hunt for the killers; and the two murderers' capture, trial, and after many appeals, eventual death by hanging. The story that Ian Frazier was hoping for -- of the writer tracking down the materials -

- does not appear in the nonfiction novel, nor in the 1967 film adaptation directed by Richard Brooks. But audiences finally got to see the "tiny figure" in a horizontal landscape in two slice-of-life biopics, Bennett Miller's Capote (2005) and Douglas

McGrath's Infamous (2006). Both films dramatize how Truman Capote, a novelist and New Yorker writer, saw the New

York Times account of the crime; went to Holcomb with his childhood friend Nelle Harper Lee; befriended Alvin Dewey, the

Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI) detective in charge of the manhunt; interviewed the accused killers and corresponded with them for years; and mined the relationship and the research to produce what he called a new form, the nonfiction novel (Plimpton 197).

In both biopics, the backstory of In Cold Blood comes to the fore: Capote's five-year involvement in events and his intimate relationship with the killers, Dick Hickock and Perry Smith -- particularly Smith, with whom he shared a similar unhappy childhood and artistic bent. Both movies show the writer not only running around in the alien landscape of Middle

America (though Capote was filmed around Winnipeg, Canada, and Texas stands in for Kansas in Infamous), but struggling to wring "the truth" from the materials. Rather than telling the full life story of the famous writer, both films dramatize a segment, covering both a historical event -- Capote researching and writing the book that made true-crime novels a wildly popular genre and him one of the best-known writers of the 1960s -- and the process by which Capote turned reporting into narrative art, which he apparently believed required hiding his role, rather than inserting himself into the narrative.

The two slice-of-life biopics not only cover the same period in Capote's life, treat the same events, and portray the same primary characters,(FN1) but they also share the same basic interpretation: Something happened during those six years that affected Capote profoundly, sending him on a downward trajectory that ended in his death at age fifty-nine. Two title cards at the close of Capote report that In Cold Blood made Capote "the most famous writer in America" but that "[h]e

never finished another book," Near the end of Infamous, Harper Lee (Sandra Bullock) tells an unseen interviewer, "There were three deaths on the gallows that night," and editor Bennett Cerf (Peter Bogdanovich) asserts that In Cold Blood

"made [Capote] and it ruined him."

Although there have been paired biopics before, sometimes referred to as "duelling" biopics (Anderson and Lupo

98), the appearance of two films about the research and writing of a forty-year-old book within a year of each other seems an uncommon coincidence. Perhaps both filmmakers recognized the debate surrounding Capote's transmutation of journalistic fact into literature as the precursor to today's debates about the possibility of constructing truthful representations. They may have assumed that in an age of infomercials, docudramas, mock documentaries, and reality television shows, audiences would be interested in the process by which Capote wrote the bestselling book of the 1960s, a true-crime novel he sold to the public as something brand new, and was instantly catapulted from regional novelist to tabloid and talk show celebrity.

Whatever impulse led to these overlapping films, we should take advantage of their synchronicity to compare them as interpretations of the writer -- the missing figure from In Cold Blood. We can also use them to develop a more sophisticated criticism of biopics -- and all history-based films -- that entails going beyond the usual practice of noting the liberties they take with the facts. Although biopics and other history films purport to tell "what really happened" and promise "the real story behind the headlines," they are better figured as adaptations of texts than as transcriptions of the historical record. We must go beyond adaptation theory, however. The challenge is to discuss biographical films, even documentary biopics, with reference to other texts, not to some presumed reality they have adapted or copied. The parallels with criticism of adaptations of classical texts are clear: In general, the "original" (in biopics, the subject's life as actually lived, or 'what actually happened') takes precedence over the "copy."(FN2)

One way to counteract cinema's "reality" effect and the perceived secondari-ness of the cinematic presentation is to make viewers aware of the artifice of the text, such as by reading for its reflexivity. Because neither of these biopics foregrounds its own process of production -- only that of In Cold Blood -- both are dominated by the codes of realism, rather than reflexivity, or at best are a combination of reflexivity and realism. Of the two films, only Infamous calls significant attention to its form by framing the six-year period that Capote worked on the project with staged interviews with seven of his intimates and friends, most of whom are characters in the diegesis. When these characters step out of their role in the action to interpret Capote's life for an offscreen interviewer, the effect may be one of artifice and thus reflexivity, but because of details the viewer learns about Capote's life before and after the years of In Cold Blood's focus, this framing device contributes to the illusion created by other conventions of the biopic: psychological depth, coherent characterization, plausible motivation, and so forth. To realize how few reflexive characteristics Infamous has, one has only to consider a biopic filmed with many Brechtian alienation effects, Tim Robbins's Cradle Will. Rock (1999). In this group biopic/backstage musical of the Depression-era arts world (featuring Marc Blitzstein, composer of the eponymous musical; Orson Welles, John Houseman, and Nellie Flanagan from the theater; and Diego Rivera and Nelson Rockefeller clashing over the Rockefeller Center murals), the acting is more stylized and self-referential than in most films of its

genre.(FN3)

Capote and Infamous offer the opportunity to change the basis of the conversation from one of object (What is the film saying? Is it telling the truth'?) to one of method (How does this film present the story, compared with how other texts tell it?). In other words, they move the emphasis from what the film says to how viewers apprehend the version presented for interpretation. And because narratives of all kinds -- filmic, oral, print -- are ephemeral, interpretation is crucial; a dominant interpretation in effect determines a narrative's meaning. This cannot be overemphasized in the case of nonfiction narratives, because they are the primary source of many people's historical knowledge. As the editors of

Retrovisions: Reinventing the Past in Film and Fiction point out, "[T]he understanding of the past by non-historians f...] is predetermined by its representation in film and fiction. [...] [W]e might say that history is the invention of creative artists as much as an objective record of true events" (Cartmell, Hunter, and Whelehan 1).

One way to counter the tendency to take the credibility of texts at face value is to demonstrate a different way of watching them. We cannot simply call for films that put in the foreground the process by which they were made, such as

American Splendor (2003) and two documentary biopics, Burden of Dreams (1982) and Hearts of Darkness (1991). As critics, we are not in the business of restricting the types of texts available, but of elucidating productive approaches to all texts. Because there can be no single interpretation that stands authoritatively above all others, a means of comprehending the strategy and judging the effectiveness of any given reality-derived text is to use intertextual approaches. The primary ways I approach these two Capote biopics through an intertextual lens are to note the genres they invoke or resemble, to consider the relationship between intertextuality and the textualization of history, to analyze the effect of their sources on their form, and to speculate about the intertexts readers bring to their apprehension of the biopics.

An overall advantage of using intertextual strategies is to keep the interpretive focus on the relations between texts, rather than between the texts and Capote's biography. Under this framework, rather than comparing the two biopics to determine which is more revelatory of the real-life Capote, viewers and critics might compare them as provisional interpretations competing for the viewer's assent. This implies analyzing features such as the radically different Capote personae created by Philip Seymour Hoffman (Academy Award winner for Capote) and Toby Jones (Infamous). Overall, the effect of the filming strategies of Capote is to view the writer as the protagonist of a classical tragedy, with Capote as the tragic figure who illustrates the psychological conception of the essential self: monomaniacal, obsessive, and unable to empathize with others.

Infamous demonstrates the role-playing self who relates to others according to the situation and context. This

Capote also manipulates his subjects, but because he has no essential self, he has no ground to reference and is therefore not likely to view his lies as lies. He adapts easily to situations and can accommodate various moral viewpoints without seeing the inconsistency in doing so. His primary mode is adaptive, whereas Hoffman's Capote can only continue the course he has started. Further, in this second biopic, Capote's portrait is painted by actor Toby Jones as a "flouncing, fluttery, gossipy, ridiculous" figure (LaSalle), akin to the Wolfgang "Wolfie" Mozart played by Tom Hulce in Milos Forman's

Amadeus (1984). One effect of this portrayal is to make us wonder how this flighty poseur could have written the clear and lucid prose of the series that sold out the New Yorker for four issues and became one of the biggest publishing phenomena of the 1960s (just as we wondered how the vulgar Wolfgang could write such ethereal music). Another is to present us with further options for interpreting the relationship between the writer and his subjects. If Capote is always playing a role, which one is it at a given time? Which are his genuine feelings, and which does he put on in order to get what he needs from the killers? As critics noted, Capote takes an objective attitude toward its subject similar to that which its eponymous protagonist exhibits toward his subjects, the killers he paints in such masterful yet detached prose.

Infamous takes a less dispassionate, more subjective attitude toward what it presents as a more vulnerable protagonist.

Capote and Infamous epitomize the textuality of history, the fact that information about this slice of Capote's life is available only through texts: narratives, documents, and oral stories. The textualization of history is by now well accepted; we commonly read that history does not give us direct access to facts, that the ideology and strategies of historians determine what gets noticed and how it is described. Also, writers -- witnesses, memoirists, compilers, and journalists -- make connections that are after the fact assumed to be embedded in the events themselves, when they are embedded only in narratives about them, Connections are made, not found. In the case of nonfictional adaptations, the plurality of sources is more obvious, because most historical and biographical sources are examples of synthetic history, made of a web of sources that include alternative interpretations of the factual record and rebuttals of competing explanations.

These twin biopics are adaptations of multiple biographical accounts -- of texts, that is, not of history itself. Their sources are forms of biographical narrative, which are in turn composed of multiple narratives, anecdotes, accounts, versions, and interpretations, as well as Capote's writings: letters, fiction, and In Cold Blood itself. Capote's nonfiction novel was the biographer's primary source (Clarke 581). Although both biopics credit a single source, these are not originals; one benefit of an inter-textual model is that it does away with the original adaptation binary. Instead, as Deborah

Cartmell notes, "we read adaptations for their generation of a plurality of meanings" (qtd. in Leitch 167), reversing the dyad so that the adaptation is "caught up in the ongoing whirl of intertextual reference and transformation" (Stain 66).

As R. Barton Palmer noted in a study of film noir as an intertextual adaptation, this method of analysis emphasizes the process by which texts are constructed, as opposed to focusing on their conventionality or the expressivity of their materials -- techniques arising from literary criticism (258). By studying the precursor texts both films cite, allude to, or borrow from, we can account for more of their different interpretations of this period of the writer's life and the divergent portraits they produce.

SOURCE BIOGRAPHIES

Each biopic credits a particular biographical work: Capote adapts a massive book with the same title by Gerald

Clarke, and Infamous takes incidents and dialogue from George Plimpton's compilation of interviews entitled Truman

Capote. What's more, the writers and directors (Dan Futterman wrote Capote, while Douglas McGrath wrote and directed

Infamous) adapt not only the themes and interpretations, but the methodology and style of their primary sources. Capote

draws primarily from four chapters of Clarke's authorized biography, which is told in standard third-person narration and is based on interviews with Capote over the last ten years of his life. The film, like the section of the biography it adapts, is tightly structured: A goal-oriented protagonist depicted in psychological depth acts consistently, and the narrative is logically causal and character driven (Bord-well, Staiger, and Thompson 13-14). Thus Capote is more similar to In Cold

Blood both nonfiction novel and film, than it is an idiosyncratic, self-conscious film that depicts the process of creation in all its confusing detail.

After an opening scene relating the discovery of the murders at the isolated Clutter farmhouse, which establishes an objective view of the murder scene, Capote stays with its protagonist, presenting his perspective on events and rarely showing him from another's point of view.(FN4) The biopic ends with the hangings and does not show the effects of the runaway success of In Cold Blood. The cinematic narration is edited seamlessly, although unlike classical Hollywood cinema, it is filmed in long takes with a nearly static camera. The effect is to stage an air of inevitability: The men must be executed so that the writer can finally complete the book he has spent years toiling on. When a court delays the execution,

Capote describes it as a "harrowing" experience, and he tells Lee (at the party for the premiere of the film adaptation of her novel, To Kill a Mockingbird). "It's torture what they're doing to me." Time seems to slow as Capote drinks heavily and becomes nearly catatonic as he waits for the men to exhaust their appeals,

Futterman and Miller focus on Capote's single-minded pursuit of the story for his own ends. We do not see much vulnerability in his character or empathy for the killers, only manipulation of them -- particularly of Perry Smith. Paralyzed with inaction, Capote is finally unable to answer their letters asking for help in finding a lawyer for another appeal, even after flying to Kansas for the hangings. The writer becomes a kind of monster -- an ironic trope, considering that Capote has urged Smith to open up to him about the night of the Clutter murders so that the book Capote is writing might save

Smith from being perceived as a monster. He has offered Smith the salvation of narrativized remorse as a character in a book. Where does Capote's own salvation lie?(FN5)

The filmmakers of Capote present a unified view of the author's character (and thus a unitary view of self) and focus on his obsessive pursuit of the story for nearly six years of his life. They tacitly accept the writer's claim that In Cold

Blood changed everything, simply by transforming reportage into literary art, while remaining "immaculately factual"

(Plimpton 198), but they also imply that Capote's seduction and betrayal of the two killers ruined his life.(FN6)

Infamous also transposes into film some of the apparatus of its source, George Plimpton's oral biography Truman

Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career (1997). The biography consists mostly of interviews conducted for the book with the questioner edited out. It includes a few published interviews with Capote, excerpts from his letters, and excerpts from Dear Genius, the memoir of his long-time companion,

Jack Dunphy. Rather than printing the interviews as stand-alone pieces, Plimpton breaks them up and distributes the fragments throughout the book, interspersing them with Capote's and Dunphy's writings. The result is a patchwork of sources, mostly oral, that the reader has to assemble into a portrait. The materials are ordered roughly chronologically, and the effect of reading the unassimilated interviews is akin to overhearing gossip; like gossip, the fragmented accounts

reveal Capote's impact on others, rather than offering a coherent whole self. Although a subject's entire life as revealed in a standard biography appears real, because the form is so familiar, the coherence is a construction, an artifact. By putting together the fragments of a life, rather than offering a seamless portrait, Plimpton gives us something less artificial. We know others in bits and pieces, not as a narrativized life, and so this composite is more accurate to our perception of others (and of ourselves). The portrait of a standard "life and times" biography presents merely a convincing illusion of a whole person.

In Infamous, McGrath dramatizes some of the interviews from Plimpton's compilation. He also stages interviews with friends who do not appear in the collection. Most notably, Lee interprets her friend's decline for the offscreen interviewer in several monologues. McGrath calls these mock interviews "testimonials." They resemble the so-called witnesses in Reds (1982), Warren Beatty's biopic of journalist John Reed: aging historical personages who were actual contemporaries of Reed and writer Louise Bryant, Although the testimonials in Infamous are given by the actors in the guise of their characters, they serve a similar function: to comment on and lend credence to the events of the diegesis.

They appear in the first fifteen and the last twenty minutes of the film, effectively framing the story. Rather than commenting on the action as it unfolds, as the witnesses in Reds do, the interviewees interpret events from a point after the dramatized period. In the last minutes of the film, Lee says, "Seeing what has happened to [Capote] since, 1 have come to feel that there were three deaths on the gallows that night." The present perfect tense implies that she is being interviewed while her friend is still alive, but perhaps after published excerpts from his work-in-progress, Answered

Prayers, cost him most of his society friends, who felt betrayed by his revealing their most intimate secrets in thinly disguised fiction.

Bringing back the major witnesses to speak about their friend's decline, apparent to all after In Cold Blood was not followed by any significant work (as editor Bennett Cerf tells the interviewer), extends the time frame by perhaps as much as a decade. Another result of this strategy is that the viewer gets hints of other causes of Capote's decline, including his growing alcoholism and pill taking. Viewers of Infamous thus are privy to more than the six-year period of the reporting and writing of In Cold Blood, which is quite unlike the effect of the single tide card of Capote that sums up the last twenty years of the writer's life and reinforces the interpretation as classical tragedy. In one of her answers to the invisible interlocutor near the end of Infamous, Lee recounts an episode about her friend during their shared childhood in Alabama that contributes another clue as to what may have led to his ambivalence toward his subjects. It is a poignant tale of adamant hope for his parents coming to see him in a grade-school pageant and his eventual disappointment, which might explain Capote's identification with Smith by filling in the sketch of a man haunted by parental absence.

Because the friends and acquaintances who are presumably being interviewed for Plimpton's biography are played by actors, the effect is akin to faux documentary and adds to the film's reflexivity. But even further, this strategy calls attention to the individual interviews in Plimpton's oral biography, which are anterior texts in two forms: They are models for the fictitious interviews invented for the film, but also tidbits of gossip, anecdotes, and theories of what made

Capote tick that make their way into the film as incidents or dialogue. Furthermore, McGrath borrowed the technique, but

not the actual testimony of Plimpton's book -- most of the people interviewed on screen are not interviewed in the book.

(The only interviewees who appear in both biography and film are socialite Diana Vreeland and writer Gore Vidal, although

Capote's partner, Dunphy, is represented in the book with excerpts from his memoir.) The fragmentation of Infamous, similar to that in Plimpton's oral biography, calls attention to the artifice of Infamous, with its many depicted sources and fragmented narratives represented in the testimonials.

In his "Note to the Reader," Plimpton warns that those interviewed sometimes contradict one another about a particular episode, and that unlike a standard life, an oral biography is edited, not narrated; therefore, there is no guide to

Capote's life in his compilation, no one to interpret events (ix). For example, Plimpton's book presents several different observers' theories about whether Capote was physically intimate with Smith, but the reader has to decide which one is true. But rather than depicting the relationship with ambiguity and leaving the interpretation up to the viewer, Infamous strongly suggests in several scenes (including one in which the two men passionately embrace) that Capote and Smith became lovers after Smith and Hickock were sentenced to hang.

To take another example, carefully reading Plimpton's volume shows that those involved disagree about who killed the Clutters -- whether Hickock killed the mother and daughter or Smith committed all four murders, as Capote asserts in the nonfiction novel.(FN7) In both biopics, Smith withholds what happened on the night of the murders -- what

Capote most desperately wants to know, as it will provide the climactic scenes for In Cold Blood. Smith finally confesses after much manipulation by the writer at similarly climactic points of both films (the scenes of Smith shooting all four victims is the single flashback in Capote, and it lasts only a minute). McGrath, writer and director of Infamous, settled on a different version based on KBI agent Alvin Dewey's statement that each man murdered two of the Clutters. Dewey says he never believed Capote's theory that Smith killed all four family members, because he knew that Smith had confessed under oath to only two murders when first apprehended (qtd. in Plimpton 174). Although Infamous depicts this alternative version of the murders in a series of flashbacks (nearly four minutes, intercut with shots of Smith explaining the complex interactions between Hickock and him that led him to start the killings), the filmmakers do not provide the reason the film attributes two murders to each man, rather than all of them to Smith. A less conventional film might have shown Dewey contradicting Capote's view or dramatized an exchange between Smith and Capote in which Smith insists that, contrary to his confession, he actually killed only two of the Clutters.

By depicting Smith's version of the murders without questioning it -- in a sequence designed to gain the sympathy of the viewer, as it does of the writer listening to his account -- Infamous assembles a psychologically verisimilar narrative, a coherent version of events with motives ascribed and effects following their causes. The certainty produced by this conventional form explains why the differences between the biographical sources are much more pronounced than those between the biopics: Plimpton does not assimilate the various interviews into a master narrative, but the film based on

Plimpton's book certainly does. Infamous is not an experimental biopic in the fashion of François Girard's Thirty Two Short

Films about Glenn Gould (1993) or Oliver Stone's JFK (1993). In the former, Girard structures a portrait of the late

Canadian pianist-philosopher (he died in 1982 at age fifty) like a fictional documentary, albeit one in fragments (the short

films range from forty-five seconds to four minutes). The thirty-two vignettes or variations (after Bach's notoriously difficult

Goldberg Variations, which Gould recorded at an early age) include performances, interviews, and other biographical scraps that the reader must assemble to achieve a portrait. In JFK, Stone provides scenes proposing alternative explanations for events and signals the film's provisional conclusions with a variety of devices. He constantly calls attention to the film's fictionality through a range of techniques, such as alternating simulations with documentary footage.(FN8) McGrath's only formal innovation that breaks the plane of verisimilitude is the use of mock interviews.

Just as we can "read" a film (or any text) with emphasis on its reflexivity, intertextuality is a reading practice as well as a characteristic of texts. If we emphasize one primary source, as in the older adaptation model, we leave out not only other important intertexts, but what Bliss Cua Lim calls the "rejoinder" of the spectator (165). Spectators who have read In Cold Blood or seen the 1967 film adaptation or the 1996 four-hour television version starring Anthony Edwards and Eric Roberts as Hickock and Smith, who have watched documentary footage of Capote or are old enough to have seen him on television,(FN9) bring these texts to the films to produce an intertextual interpretation. Some viewers may have read Clarke's or Plimpton's biography or a print interview with Capote. Readers of The Muses Are Heard or other journalistic works, such as his profile of Brando in the New Yorker, have even more intertexts echoing in their minds and are likely to pick up allusions to these other works in the film. For example, in Infamous, Capote mentions his profile of

Brando to Smith to earn his confidence (he has learned that the accused killer has intellectual pretensions); later in the film, when Smith has learned the title of Capote's book, he accuses the journalist of double-timing the two men, just as he

"betrayed Brando." The spectator who has not read the New Yorker profile of Brando may seek it out, making it an antecedent text to Infamous only after the fact.

Both biopics imitate or allude to many visual texts: landscape photographs,(FN10) documentaries such as the

Maysles brothers' A Visit with Truman Capote (1966), and the author's appearances on television talk shows; other biopics and other genre conventions (the narrative are of Capote that rises toward revealing what happened in the Kansas farmhouse that night is similar to the suspense genre; Capote also has noir overtones). In Capote, Richard Avedon's photographs for the New Yorker are re-created with the actors in character. If the viewer of either film has not read its primary source or In Cold Blood, on which both films are partly based, the audience's dialogic response may have little to do with credited sources and much to do with intertexts, such as these visual ones, other true-crime novels or films, or representations of openly gay men in films and television.

As a gesture of intertextuality, the screenwriters have occasionally borrowed dialogue from each other's primary source. In Capote, the writer tells Lee about the strange identification he feels with the smaller and more artistic of the two killers. He claims that, in some way, he and Smith are the same person: "I feel like we grew up in the same house but

Perry Smith went out the back door and I went out the front." This dialogue beautifully transforms the way Marie Dewey

(the KBI agent's wife) reported a remark by Capote: "Truman said [...] in life you follow a path, and all of a sudden you come to a fork in the road, and either you take the left or you take the right, and he said in this case he felt he took the right and Perry the left" (qtd. in Plimpton 173). And McGrafh borrows a sentence from Clarke's biography for Lee's

testimonial about why she jumped at the chance to accompany Capote to Kansas to cover the effect of the crime on the local residents. Lee recalls that, because she was drawn to crime (her father was a lawyer, as is Atticus Finch in To Kill a

Mockingbird, which she had recently completed), she immediately wanted to go, explaining, "It was deep calling to deep"

(qtd. in Clarke 319).

Infamous suggests other ways Capote might have written In Cold Blood, such as by acknowledging his role in events -- as Frazier says, "himself, small, running round" (qtd. in A1s 59). When Capote is establishing his bona fides as a writer to Smith, he mentions his novel Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), in addition to his profile of Brando. In this early conversation, Capote also describes The Muses Are Heard (1956), in which he told the story of a troupe of African

American opera singers performing Gershwin's Porgy and Bess in Moscow, by saying, "It treats real people with the emotional and psychological detail of a novel." In this way, Capote admits to Smith that he turns his subjects into characters, trimming them to fit his literary conception, by writing what they should have said or done.(FN11)

Another significant effect of using intertextuality as a reading strategy is to encourage audiences -- viewers, reviewers, and critics alike -- to trace referents to other texts, rather than to history. The coincidence of the two biopics is especially useful in allowing audiences to compare the biographical "truth" they depict, which includes how Capote transformed his interviews into dramatic narrative form. It is not simply that one film depicts the writing process and the other does not, for we see some of Capote's process of writing in both films. In Infamous we see Capote writing in longhand on yellow legal pads, the page blank except for the words "Answered Prayers," revealing the writer's block with which he struggled after completing In Cold Blood. In contrast, Capote mystifies the creative process: The writer returns from interviewing the people of Holcomb or the killers, sits at his typewriter, and produces box after box of notes and manuscript. Most other references to the work-in-progress are Capote's claims to journalists and friends about what he hopes to achieve in this new form, and New Yorker editor William Shawn's feedback after he reads drafts of early sections of In Cold Blood: "I think it's going to change how people write."

Infamous reveals more of the process of fictionalizing -- that is, the methods by which the writer converts his reporter's notes to artful narrative. For example, the film dramatizes Capote's process of rehearsing multiple versions of his sources' accounts for his nonfiction novel, such as by improving dialogue. One sequence of brief shots comes after

Smith finally relates his story of the murders, including confessing the details of killing Herb Clutter, the first of the family to die that night. He apparently gave Capote a version of one of the most notorious sentences of In Cold Blood: "I thought he was a very nice gentleman. I thought so right up to the moment I cut his throat" (275). But we do not hear this in the extended flashback sequence intercut with shots of Smith telling the story to Capote; instead, the author auditions three variants of the remark with different friends in three very brief shots, followed by a shot of the three versions of the sentence written longhand on a yellow pad, with a check mark by the one Capote will use in the novel.(FN12)

Another indicator of Capote's fictional methods in Infamous comes early in the film in an argument between Lee and Capote over the latter's description of his work as a "nonfiction novel," When the two are separately writing up their notes after a day of interviewing Holcomb residents, Lee says, "A work cannot be both 'nonfiction' and a novel." Capote

points out that Mockingbird is based on her life, but she invented certain details. "Yes," she replies, "it's a novel." To her, nonfiction means re-creating, not creating. While this scene serves as a sign of process in the movie, it does not represent the self-accounting form Frazier and others were looking for. Both Lee's and Capote's positions rest on the older paradigm of objectivity, which asserts, "This is the way it was." Like Capote, the film Infamous shares the worldview of In Cold

Blood: In a 1965 New York Times Book Review interview, Capote told Plimpton that he decided what the truth was and always went toward that, undercutting or qualifying versions he did not agree with by how he chose to tell it (Plimpton 203-

04). Although this approach is depicted in the film, Infamous does not represent a new paradigm in its cinematic techniques. Nevertheless, it is easier to read as a construction, as a single interpretation, than is Capote; this is due in large part to the multivalent, polyphonic source text, but also to the texts that echo within it.

Infamous clearly borrows one famous shot from Brooks's In Cold Blood. In the black-and-white film adaptation of

Capote's book, just before Smith is summoned to the warehouse where he will be executed, he stands next to a window with rain falling steadily outside, reminiscing to the chaplain about the last time he disappointed his abusive father. During the two-minute scene (it is intercut with flashbacks of the story Smith is narrating), the rain tailing down the window throws shadows on Smith's face in the shape of tears. The projected tears produce the effect of pathos, which one would expect in such a doomed man, but his voice is fiat, his face unexpressive. Because these contradict the emotion, the shot expresses Smith's deep ambivalence toward his father, whom, he tells the chaplain, he both loved and hated.

Near the end of Infamous, a briefer shot, this time of Capote, echoes that long-held shot Capote is in Kansas for the execution but cannot bring himself to go to the gallows. He stands in front of an identical window with rain outside coming down hard. The raindrops are not reflected on his face, but the angle is the same. In the scene, we detect

Capote's ambivalence about the impending fate of "the boys." He tells Bennett Cerf, the editor who accompanied him to

Kansas, that he cannot help them anymore (he does not really want to, since he cannot finish his book until they hang).

He adds that he hopes Smith will apologize, in order to appear more sympathetic in the book. (Smith, frightened into inarticulateness by the sight of the noose and trap door, disappoints Capote by going to his death saying only, "Adios, amigo." But Capote simply revises the story in the telling -- both to his friends back in New York and in his book.)

We might call this shot in Infamous a "matching" intertextual shot, for it alludes to a previous one that many viewers will recognize, and also echoes the ambivalence of the earlier one.(FN13) In Capote, too, there may be a thematic equivalent of this same scene from In Cold Blood. It occurs at the climactic point of Smith's detailed account of events at the Clutters' in November 1959. As Smith reminisces about how he disappointed his father (he tells a similar story in the precursor shot of In Cold Blood), a tear runs down his face just before the one-minute flashback to the murders. As is consistent with Capote's, focus on the writer, rather than his subjects, Smith does not describe in detail his relationship to his parents. He simply says, "There must be something wrong with us that we could do that."

CONCLUSION

One important criterion to use in evaluating a biopic is the sign of its making, the filmmakers' relation to their

materials. When actual events, people, movements, and processes are depicted in cinema, viewers need signs of the process of production, or the story of the producer's relation to materials, to be able to question the illusion so painstakingly created. Viewers should be reminded they are watching a movie, that although it has a reported or historical basis, it is fiction. In the case of these biopics, the way is paved because of their reflexive plots staging the process of gathering information and producing a book. It is just a step to see that the writer's life is also a construction, for we are privy to the process of gathering information just as biographers, including the screenplay writers, learned plausible accounts of sequences of events and developed interpretations of the life of Truman Capote. Going beyond reflexivity to the conception of intertextuality (lately used to increasing advantage by adaptation studies) aids immeasurably in reading even the standard biopic to locate the texts that resonate within it, enabling the analysis of their effects, one of which is making viewers aware of the artifice of all texts and of their own participatory role in constructing them.

Even the spectator with little experience of Truman Capote, the crime that he narrated and spun to celebrity heaven, or the world of the New Yorker is likely to have read To Kill a Mockingbird, or to have seen the 1962 film version, to recognize still photographs of the Plains states, and to know what a Faustian bargain is. Because intertextuality is not always intentional, it is impossible to say what certain scenes from a biopic stimulate in a given person. As Lim points out, if an actor or action evokes resemblances, imitations, echoes, or allusions to texts in her conscious or unconscious mind, it may be because the familiar figure or the theme cited or echoed "is not a singular point of meaning but a variegated prism through which other discourses are refracted" (165). If spectators and reviewers are convinced of the desirability of this method, we would be on the way to avoiding the essentialism entailed in the more common practice of evaluating biopics -- and history-based films in general -- based on their accuracy or authenticity.

ADDED MATERIAL

Phyllis Frus teaches in the film studies program at Hawai'i Pacific University. She is working on a guide to the many genres of reality film, tentatively titled True Stories on Screen: A Viewer's Guide in Fact-Based Film.

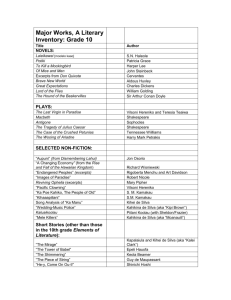

Truman Capote (Toby Jones) in Douglas McGrath's Infamous. Photo courtesy of Photofest.

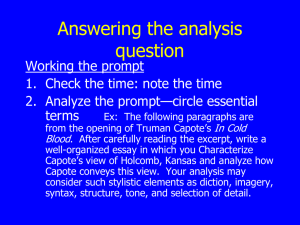

Truman Capote (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and Nelle Harper Lee (Catherine Keener) survey the stark Kansas landscape in

Bennett Miller's Capote. Photo courtesy of Photofest.

FOOTNOTES

1. When the biopics alter a character, they choose the same one; Rather than introduce his Random House editor Joe

Fox, the historical character who accompanied Capote to Kansas for the executions in April 1965, both decide that the confidant and adviser figure shown throughout should also travel to Kansas to hold the valuable writer's hand. In Capote, the confidant is William Shawn, the famously austere editor of the New Yorker, in Infamous, it is senior Random House editor Bennett Cerf.

2. The critical literature on adaptation is filled with expressions of impatience over the persistence of the source-adaptation

model. See Leitch for an overview of the problem. See Rosenstone for the equivalent treatment of history film, even by historians who "use written works of history to critique visual history as if that written history were itself something solid and unproblematic" (49).

3. Robbins seems to pay tribute to Brecht's politics by directing the actors in deliberately broad fashion to evoke a

Brechtian aesthetic.

4. One exception is a moment at a party in New York when Capote's partner, Jack Dunphy, and Nelle Harper Lee eavesdrop on Capote, who is regaling listeners with an anecdote about the hard-bitten convicts he has just interviewed. "It looks like the beginning of a love affair," says Dunphy. "Yes," retorts Lee, "Truman in love with Tinman" (Capote).

5. Victoria Segal explains the audience's feeling of being toyed with in this way: "[A]t times you feel Capote is merely helping the killers secure good lawyers so he can keep them alive to get his story, much like turkeys being fattened up for

Christmas; at others you are encouraged to believe that Capote is falling in love with Smith, that his friendship and grief are real" (48).

6. Roger Ebert sums up the message of the film that most reviewers repeated in some form: "As Capote gets to know [the killers], he's consumed by a story that would make him rich and famous, and destroy him. [...] In Cold Blood became a best-seller and inspired a movie, but Capote was emotionally devastated by the experience and it hastened his death."

David Edelstein writes that in the hands of Miller and Futterman, "the grim story of Truman Capote and his seminal nonfiction masterpiece becomes a tale of duplicity and self-loathing -- of the loss of a writer's soul and the beginning of the end of his artistry."

7. Capote did not think Hickock was capable of murder, and he interpreted Smith's killing of the Clutters as the symbol for everything missing in the young man's life (Plimpton 174, 203).

8. Stone told interviewer Mark Carnes, "The film is looking at itself, conscious of itself. It moves from black-and-white to color; the angles are offbeat. Somebody says one thing in an external moment, but then the movie cuts to an internal moment and you see another expression wholly opposite" (307). It should be noted that New Orleans district attorney Jim

Garrison, not President Kennedy, is the biographical subject of JFK. (Stone credits two sources, Garrison's On the Trail of the Assassins and Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, by Jim Marrs, as well as 'public sources.') Although the film about Kennedy's assassination is self-conscious and formally innovative, this slice of Garrison's life -- years spent attempting to bring those he believes to be the actual assassins to justice -- gets conventional biopic treatment.

9. Capote appeared regularly on talk shows hosted by Dick Cavett, Johnny Carson, and Merv Griffin.

10. Miller told an interviewer that photographs were the primary influence on Capote's style and that he adopted "a prose approach to filmmaking -- a very restrained, very austere tone that would sensitize [the viewer] to the subtlest aspects of the story." He explains that the long, still shots of the landscape that are like stills are meant to divide scenes like chapter divisions in a novel, as well as to serve as establishing shots (Bowen).

11. Muses anticipates a more self-accounting form of New Journalism, for the narrator refers to himself as participant as well as observer, and covers the process of mounting the production as well as Muscovians' reactions to the black

American performers. If made into a film with the journalist as the protagonist, Muses would be similar to Almost Famous

(2000).

12. In the DVD commentary, McGrath says he showed Capote experimenting with three ways to report Smith's account of his actions as a means of dramatizing his contention that the journalist made up all the dialogue in his nonfiction novel, especially since Capote brags about not having used a tape recorder (Infamous).

13. Another significant example in a biopic of a sequence of shots that refers back to an earlier film is Raging Bull (1980).

On the DVD commentary, Scorsese says he based one of the fight scenes shot for shot on the shower scene in Psycho. It may have been an homage, a common type of intertextuality, but the shock of that scene carries over to anyone who recognizes it; thus we should be grateful he did not imitate the sequence in one of the scenes in which boxer Jake

LaMotta batters his second wife, Vicki.

WORKS CITED

Als, Hilton. "My Lunch with Ian; Practicing Personable Journalism." Rev. of Great Plains, by Ian Frazier. Village Voice

20 June 1989: 59.

Anderson, Carolyn, and Jon Lupo. "Hollywood Lives: The State of the Biopic at the Turn of the Century." Genre and

Contemporary Hollywood Ed. Steve Neale. London: BFI, 2002. 91-104.

Bordwell, David, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson. "Story Causality and Motivation." The Classical Hollywood

Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to I960. New York; Columbia UP, 1985.

Bowen, Peter. "Casualties of Fame." Interview with Bennett Miller. Filmmaker 25 October 2005. 15 April 2008

< http://www.filmmakermagazine.com/fall2005/features/casuallies_of_f ame.php>.

Capote. Dir. Bennett Miller, Perf. Philip Seymour Hoffman and Catherine Keener. Screenplay by Dan Futterman. 2005.

DVD. Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, 2006,

Capote, Truman. Answered Prayers: The Unfinished Novel. New York: Random House, 1987.

Capote, Truman. "The Duke in His Domain." [Profile of Marlon Brando]. New Yorker 9 November 1957, 15 April 2008

< http://www.newyorker.com/archive/>.

Capote, Truman. In Cold Blond: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences. New York: Random

House, 1965.

Capote, Truman. The Muses Are Heard: An Account. New York: Random House, 1956.

Cames, Mark. "A Conversation Between Mark Cames and Oliver Stone." Past Imperfect: History According to the

Movies. Ed. Cames. New York: Henry Holt, 1996. 305-12.

Cartmell, Imelda, I. Q. Hunter, and I. Whelehan, eds. Retrovisions: Reinventing the Past in Film and Fiction. London:

Pluto Press, 2001.

Clarke, Gerald. Capote: A Biography. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Ebert, Roger. Rev. of Capote, dir. Bennett Miller. Chicago Sun-Times 21 October 2005. 3 November 2007

< http://rogerebert.suntimes.com>.

Edelstein, David. "The Truman Show." Rev. of Capote, dir. Bennett Miller. Slate 29 September 2005. 3 November 2007

< http://www.slate.com/id/2127120/>.

In Cold Blood. Dir, Richard Brooks. Perf. Robert Blake and Scott Wilson. 1967.DVD. Columbia Tristar, 2003.

In Cold Blond. Dir. Jonathon Kaplan. Perf. Anthony Edwards, Eric Roberts, and Sam Neill. 1996. DVD. Platinum Disk,

2005.

Infamous. Dir. Douglas McGrath. Perf. Toby Jones and Sandra Bullock. Screenplay by Douglas McGrath. 2006. DVD.

Warner Home Video, 2007.

JFK. Dir. Oliver Stone. Perf. Kevin Costner, Kevin Bacon, and Tommy Lee Jones. 1991. DVD Warner Home Video,

1997.

LaSalle, Mick. "Infamous Takes Another Crack at Uncovering Capote." San Francisco Chronicle 13 October 2006, 3

November 2007 < http://www.sfgate.com>.

Leitch, Thomas. "Twelve Fallacies in Contemporary Adaptation Theory." Criticism 45.2 (2003): 149-71.

Lim, Bliss Cua. "Serial Time: Bluebeard in Stepford." Film and Literature: A Reader. Ed. Robert Stam. Oxford:

Blackwell, 2005. 163-90.

Palmer, R. Barton. "The Sociological Turn of Adaptation Studies: The Example of Film Noir." A Companion to Literature and Film. Ed. Robert Stam and Alessandra Raengo. Madison: Blackwell, 2004. 258-77.

Plimpton, George. Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His

Turbulent Career. New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 1997.

Raging Bull. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Perf. Robert DeNiro, Cathy Moriarty, and Joe Pesci. 1980. DVD. MGM, 2005.

Reds. Dir. Warren Beatty. Perf. Warren Beatty, Edward Herrman, and Diane Keaton. 198), DVD. Paramount, 2006.

Rosenstone, Robert. Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our Idea of History. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1995.

Segal, Victoria, "Writing Crime." Rev. of Capote, dir. Bennett Miller. New Statesman 27 February 2006: 48.

Stam, Robert. "The Dialogics of Adaptation." Adaptations, ed. James Naremore. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2000. 54-

76.

Thirty Two Short Films about Glenn Gould, Dir. François Girard. Perf. Colin Feore. 1993. DVD. Sony, 2001.