1. An Overview of Urban Growth: Problems, Policies, and Evaluation

advertisement

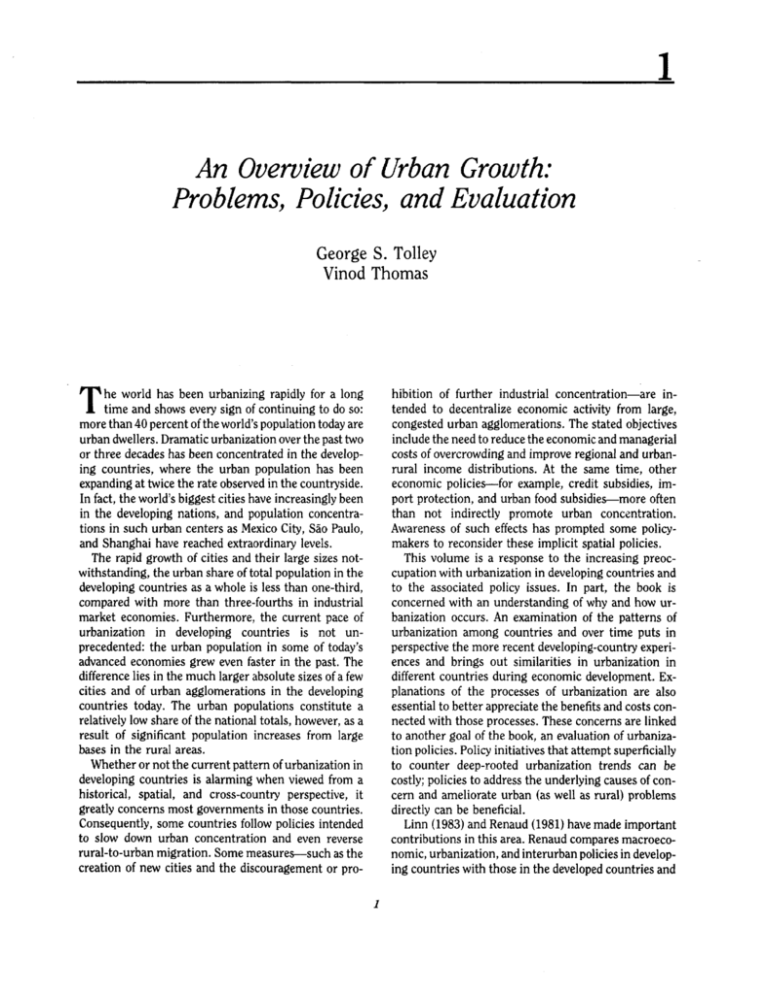

1 An Overviewof UrbanGrowth: Problems, Policies,and Evaluation George S. Tolley Vinod Thomas The world has been urbanizing rapidly for a long T time and shows everysign of continuing to do so: more than 40 percent ofthe world'spopulationtodayare urban dwellers.Dramaticurbanizationoverthe past two or three decadeshas been concentrated in the developing countries, where the urban population has been expandingat twicethe rate observedin the countryside. In fact, the world'sbiggestcitieshave increasinglybeen in the developingnations, and population concentrations in such urban centers as MexicoCity,Sao Paulo, and Shanghai have reached extraordinarylevels. The rapid growth of cities and their large sizes notwithstanding,the urban share oftotal populationin the developingcountries as a whole is less than one-third, compared with more than three-fourths in industrial market economies. Furthermore, the current pace of urbanization in developing countries is not unprecedented: the urban population in some of today's advancedeconomies grew even faster in the past. The differencelies in the much larger absolutesizes of a few cities and of urban agglomerationsin the developing countries today. The urban populations constitute a relativelylowshare of the national totals, however,as a result of significant population increases from large bases in the rural areas. Whether or not the current pattern of urbanizationin developingcountries is alarming when viewedfrom a historical, spatial, and cross-country perspective, it greatly concerns most governmentsin those countries. Consequently,some countries followpoliciesintended to slow down urban concentration and even reverse rural-to-urbanmigration. Somemeasures-such as the creation of new cities and the discouragementor pro- hibition of further industrial concentration-are intended to decentralize economic activity from large, congested urban agglomerations.The stated objectives includethe needto reduce the economicand managerial costs of overcrowdingand improve regionaland urbanrural income distributions. At the same time, other economic policies-for example, credit subsidies, import protection, and urban food subsidies-more often than not indirectly promote urban concentration. Awarenessof such effects has prompted some policymakers to reconsider these implicit spatial policies. This volume is a response to the increasing preoccupationwith urbanization in developingcountriesand to the associated policy issues. In part, the book is concerned with an understanding of why and how urbanization occurs. An examination of the patterns of urbanization among countries and over time puts in perspectivethe more recent developing-countryexperiences and brings out similarities in urbanization in differentcountries during economicdevelopment.Explanations of the processes of urbanization are also essentialto better appreciatethe benefitsand costsconnectedwith those processes.These concerns are linked to another goal of the book, an evaluationof urbanization policies.Policyinitiativesthat attempt superficially to counter deep-rooted urbanization trends can be costly;policiesto addressthe underlyingcausesof concem and ameliorate urban (as well as rural) problems directly can be beneficial. Linn (1983)and Renaud (1981)havemade important contributions in this area. Renaud comparesmacroeconomic, urbanization,andinterurban policiesin developing countries with those in the developedcountries and 1 2 GeorgeS. Tolleyand VinodThomas discusses the need to correct the undesirable spatial effects of national economic policies, make internal management of cities more efficient,and increase economic efficiencyby eliminating barriers to mobilityof resources and dissemination of innovations. Linn focuses in greater detail on intraurban issuesand on how to increase the efficiencyand equity of growing cities. He coversa wide range of areas-urban employment, income distribution, transport, housing, and socialservices-and evaluates the effectivenessof such policy instruments as public investment,pricing,taxation,and regulation. This study focusesmore sharply on the policyissues connected with concentration and decentralization. Evaluation methods and quantitative assessments of policy effectshave been drawn from the experiencesof different countries. The book complements the more general urban review of Renaud and the city-specific findingsof Linnin that it seeksto sharpenthe economic analysis and evaluation of urbanization policies at the national and city levels.A unique aspect of this book is its attempt to deepen our understanding of the economic benefits and costs of urbanization and urban policyinterventionswithout denyingthe contributionof other disciplinesto an understanding of urbanization. Patterns of Urbanization In comparisons of urbanization it must be kept in mind that countries do not report their urban populations uniformly. The reasons for nonuniformity range from use of differentcriteria in defining urban areas to differencesin conceptsand in the accuracyof statistics among countries. Furthermore, global data for the urban sector usually gloss over important intraurban differencesamongcountries, includingvariations in the definition and nature of large as against small cities. Statisticson urbanizationshouldthereforebe usedwith caution and perhaps only for broad comparisons. Historical Comparisons Someargue that developing-countryurbanizationtodayis qualitativelydifferentfrom the historical pattern in today'sdevelopedcountries. The main differencerelates to the absolute levelsof urbanization today,which in good measure are basedon large overallpopulations. High levels of absolute povertyare also associatedwith urbanization.During 1970-82 the developingcountries experienceda more rapid urbanization than did the industrial countries (table1-1).Theorders ofmagnitude are even more striking between 1950 and 1980,when the urban areas of the developingcountries (excluding China)absorbednearly 600 million additionalpeopletwice the total number of urban dwellersin industrial countries at the beginning of that period.' If the recent trends continue, an additional 1 billion urban dwellersmaybe added in developingcountries by the end of this century.The magnitudesare historically unique. Unprecedentedconcentrationof peopleis likely to prevail in several cities in the developingcountries which are alreadyamong the biggesturban agglomerations in the world. Accordingto U.N.projections, Mexico Cityand Sao Paulo each may contain more than 25 million people by 2000, closelyfollowedby Shanghai, Beijing,and Riode Janeiro; of the twenty-fivecitiesthat are likelyto have more than 10 million people,twenty are expectedto be in what are now considereddeveloping countries. The magnitude of this growth is likelyto compound the problems of managing cities and of addressing absolute poverty and unemployment. Although the sheer magnitude of urbanizationandof associated problems in developingcountries is phenomenal, some other salient aspectsof the present urbanization pattern do not depart markedly from past experience.A comparison of trends over many years revealsno dramatic changes in the growth rate of the world's urban population. The share of the world's population in urban areas has increasedsteadily,from an estimated3 percent in 1800to more than 40 percent today, but the percentage change per decade in the Table 1-1. UrbanPopulation: Share and Growth, by Country Group (percent) Urbanpopulation as share of total population Country group 1960 1982 Averageannual growth in urban population 1960-70 Averageannual compound growth in urban share, 1970-82 1960-82 Low-income 17 21 4.1 4.4 Middle-income 33 46 4.4 4.2 Industrial market 68 78 1.9 1.3 Industrial nonmarket 48 62 2.6 1.8 Source:WorldBank(1984),annextable22, p. 260;the lastcolumnis derivedfromthe firstfour. 1.06 1.67 0.69 1.29 An Overviewv of UrbanGrowth proportion that is urban has remained around 16 percent during this period.2 Asseen in table 1-1the developing countries today are adding to their urban populations more rapidlythan are the developedcountries, but these rates are not very unlike those observedduring earlier periods of urbanization in what are now developed economies. Hence, the long-term processes under way are not totally surprising. Comparisons among Countries Behind the total figures on urban population lies a variety of individual country experiences.LatinAmerica is by far the most urbanized among the developing regions; some two-thirds of its populationlive in urban centers. In contrast, low-income Asia and Africa are predominantlyrural, with averageurbanization levelsof 25 percent. Intraregional differencesare also significant: the urban share is about 83 percent in Argentinaand 46 percent in Ecuador: it is 24 percent in India and 12 percent in Bangladesh. Notwithstanding these differences, some comparisons seem to apply broadly across countries. Descriptively, a clear and well-knownassociation is observed between income level and the percentage of population which is urban. Asshown in table 1-1,for countrieswith low incomes, 21 percent of the total population was urban in 1982. In contrast, 46 percent of the population was urban in middle-income countries, and 78 percent was urban for the higher-income industrial market economies.Abroadpositiveassociationbetween income levels and degree of urbanization also seems to hold within regions. (There are, of course, many exceptions to the simple relation between income level and the percentage of population that is urban.) Furthermore, growth in urban populationappears to have a tendency to decline with rising incomes. This tendency is reflected in differencesin the rate of urban population growth among countries with different incomes. During 1970-82 urban population grew at 4.4 percent annually in the low-incomecountries and at a much higher rate if China and India are excluded.In the middle-income countries urban population growth was 4.2 percent annually, whereas for the high-income industrial market economiesthe urban populationgrowth rate was only 1.3 percent a year. These regularities in urbanization in developing countries might be expectedas part of the development process. Some aspectsof present-dayconcentration may nevertheless be considered especially noteworthy. A tendency often noted is that largeportions of the populations of rapidly developingcountries tend to be concentrated in one or a fewcities. For the low-incomecountries, on average, 16 percent of the populationwas in the 3 largest city in 1980. In the middle-incomecountries the proportion was substantially higher, 29 percent. In the industrial market economies, however, it was only somewhat higher than in the low-incomecountries-18 percent. Because of the high representation of rapidly growing countries in the middle-income group, the figures lend some support to the observationthat one way in which rapidlydevelopingcountries of todaydiffer from countries that underwent developmentearlier is in the tendency for their urbanization to be more heavily concentrated in large cities. In fact, the overcrowdingin one or a few cities, and the visible poverty connected with this phenomenon, are of prime concern; the overall level and rate of urbanization in the country as a whole are less prominent issues. Some Generalizations Some relations between urbanization and economic developmentcan be further distinguishedwith the help of simple descriptiveregressions. For sixty-sixlow- and middle-income economiesfor which data are available, regressions have been run using the followingindependent variables: (1) the per capita income rank of the economy, (2) the percentage rate of growth of per capita income, (3) the percentage rate of growth of total population,and (4) zero-onevariablesthat represent the region in which the economy is located. (For example, for an economy in Asiathe Asiavariable takes on a value of one and the values of all other regional variablesare zero for that economy.) Degree of Urbanization. When the independentvariables listed aboveare used in a first-regressionequation to explain urbanization, as measured by the percentage of the population that was urban in 1980, a high degree of association is found. The multiple regression coefficient, R2, is 0.769. The most significant variable in explaining the percentage of the population that is urban is the income rank. Thisfinding corroboratesthe positive relation already noted between income and the degree of urbanization. The growth of total population has a significant negative effect in explaining the percentage of the population that is urban. This result may be attributable to slow population growth in higherincome countries, which, in viewof the positiveincomeurban relation, also tend to be the most highly urbanized. The growth of per capita income has a negative, though less significant, coefficient in explaining the urban share of population. The most rapid percentage gains in per capita income occur in countries other than those which already have high levels of income and urbanization. Thus, countries with the most rapidly rising incomes usually have not yet reached the highest 4 6 GeorgeS. Tolleyand VinodThomas GeorgeS. Tolleyand VinodThomas which are discussedin casestudydetail in later chapters-and pointsoutthat urbanizationandits accompanyingphenomenaare productsof wider development processes.Caremustbe takenin the designof measures and policiesconcerningurbanizationto avoidextreme correctiveactionsthat mayhamperdevelopment. UrbanPoverty Themostwidelyobservedandacutelyfelturbanproblem in developingcountriesis the largenumbersofpoor and unemployedpeople in the cities. The extent of poverty in the economyas a whole dependson the degree of economicdevelopment.Urban poverty is viewedas part ofoverallpoverty;the ruralpoormoveto urban areas, which tends to broadlyequilibratereal incomesacross locations.Povertyis related in great measureto the sizeofthe low-skilledpopulation,which is distributedamongurbanand ruralareasaccordingto economicandother considerations that affectthe entire population. Growthof productionleadsto growthin demandin urban areasfor all factorsof production,includingunskilledlabor.The changein the proportionof unskilled workersin urban areas dependson growthin demand forurbanand nonurbancommodities, on substitutabilities betweenunskilledworkersandother factorsofpro- that initiallymakeupa smallpartof the economy,most oftenin the urbansector,in earlystagesofdevelopment. Therise in marginalproductivityof all labor,including unskilled labor, may be slow at first and then may accelerateas a greater proportionof the economydevelops.Asthe marginalproductivityoflaborrisesin the courseofdevelopment,the incomesof thoseat the low end of the incomescalealso rise. Furthermore,since developmentincreasesthe returns to educationand other formsofhumancapitalinvestment,manypersons whowouldotherwisebeunskilledtransformthemselves into skilledlaborersand thus directlyraise their incomes.The number of unskilledemployeesfalls,and their marginalproductivityconsequentlyrises. Urbanization, whichaccompaniesthe strengthening of comparativeadvantagesin urban sectorswith develvisiblepovopment,can be associatedwithconsiderable ertyand otherurbanproblems,particularlyas unskilled workersbecomedisplacedfromtraditionalruralactivities. Sustainedandcontinueddevelopmentovera long time wouldbe desirableto ameliorateadjustmentproblems and increasinglyabsorbthe previouslyunskilled laborersinto the developingeconomy.The origins of urban problemslie in inadequateand unsustaineddevelopmentandrural-urbanadjustment,but thoseare by no meansthe onlysourcesof difficulties. duction, and on the comparative decline of so-called traditional production in urban and in rural areas. Tra- ditional productionmay be definedas productionby firms or householdswhich,althoughthey can modify their output and techniquesin responseto changesin pricesofproductsandfactors,are not viablein the face of competitionfrommoderndomesticor foreignmanufacturingor from modern farmingenterprises.Traditional productionusuallyuses unskilledlabor,and its declinemayreleaseunskilledlaborto other parts ofthe economy.Althoughsomeanalystsexplaineconomicdeasa declinein traditionalproducvelopmentexclusively tion, developmentis here viewedas a broaderprocess whichinvolvesan accumulationandtransferof knowledgethat could and probablywould occur evenif no units becameunviable.Thelarge-scaledeclineof industries that engagein traditionalproductionmaybe an important accompanimentof developmentin some countries-since the declineis accompaniedby substitutionof capitalfor laborand byintroductionof new techniques-but in other countriesthisprocessmaybe an unimportantdetail.Otherthingsbeingequal,if the declinein traditionalproductionis greaterin ruralthan in urbanareas,the proportionof unskilledworkersand henceof poor city residentswill increase. Even in the absenceof traditionalproduction,developmentmaybe concentratedin industriesor firms Increasingconcentrationof economicactivitiesand peoplehas beenviewedas a reflectionboth ofdevelopment and of economicdeterioration.Asalreadynoted, whereasthe generallyhigherincomesin urbanareasare associatedwith the benefits of urbanization,urban poverty and unemploymentand a host of problems associatedwith pollutionand congestionare the most noted indicatorsof urban failure.Embeddedin the urbanizationprocessare elementsthat representdevelopmentandthat deserveto be promoted,but urbanization alsobringswith it extemalitieswhichcan bring about overcrowding. Three types of externalitiesmay be associatedwith overurbanization.First, environmentalexternalities, suchas thoseconnectedwithpollutionandcongestion, can meanthat cities'sizesare larger thanwouldmaximizenational(orregional)incomeandwelfare.Second, protected employmentthat maintains urban wages abovemarket-clearinglevelsmaymakecitieslarger or smallerthantheyotherwisewouldbe,dependingon the elasticityof demandfor labor.Third,the attractiveness of urban areas (becauseof the availabilityof free or subsidizedpublicservicesandthe advantagesofproximityto governmentactivities)canleadto excessiveurbanization. Going beyond these urban externalities,a An Overviewof Urban Growth hypothesisofferedhere is that the phenomenonof great urban concentration in one or a fewcities is connected with the difficultyand relativelyhigh cost of providing intercity transport in developingcountries, and that more general infrastructure decisionsalso playa role. Urbanization Policy in Market and Mixed Economies Some of the differencesamong today's developing countries that merit attention are emphasizedby Renaud in chapter 5. In many of today'sdevelopingcountries additions to population are larger, income levels are lower,and opportunitiesto relievepopulationpressures through migration are more limited than in others. Urbanizationin today'sadvancedeconomiespresents a differentset of issues.In some countries there is a processofa slowdownandan eventualend to urbanization and the emergenceof yet another industrial revolution based on new technologieswhich are less tied to concentrated manufacturing centers. ChapterS providesa reviewof urban-relatedproblems in developingcountries-regional inequalities,congestion, pollution, and inadequateprovisionof urban services-and a threefoldclassificationof relatedurbanization policies:nationaleconomicpolicies,such as import controls, that havespatial effects;explicitregional development policies,such as investments in infrastructure; and policiesconcerned with the management of cities.Problems and policyemphasisvaryamong countries: they are influenced by the age-old structure of cities in Asia, the rapid urbanizationwhich has been going on for some time in LatinAmerica,and the new urbanization in several parts of Africa,which started from a low base and is proceedingat unprecedented rates. National economicpolicy sometimes producessignificant and unintended effectson urbanizationwhich may outweighany direct and intendedeffectsof urbanizationpolicies.The unintendedspatialbiasesof national economic policiesusually favorsome urban centers andare commonlygeneratedthrough trade policiesthat protect the manufacturingsector. For example,credit allocation,public investment,and pricing policiesmay give preferentialtreatment to economicactivitiesthat are concentrated in a few cities and regions.The management practices of the central government and its regulation of economicactivities,which make location closeto the capitalnecessaryor advantageousfor firms, also contribute to the urban vortex. Explicit regional development policies sometimes attempt to favor decentralization,but they are not alwayssuccessful or efficient.An unintendedby-product 7 of regulations in India that favored rural over urban developmenthas beenthe encouragementofthe growth of the urban underground economy.The use of water resourcesfor regionaldevelopmentpurposesin Malaysia has been dramatic,and policyattention to leakagesand regional multipliers has been greater than usual. The Republicof Korea,becauseof its shortageof land,has an intense interest in land-use guidelines(see chapters 5 and 8), but in spite of prohibitions and incentives,export-oriented growth policiesand industrializationensured that the largest urban centers, especiallySeoul and Pusan, would continue to grow. Venezuela and Brazilhavepursued industrialdeconcentrationpolicies, with limited success(chapters 9 and 13). In additionto policy incentives or disincentives,the balance of labor market considerations, economies of scale within an industry, and the effectof the total size of a city determine location decisions(chapter 7). The appropriateinternal managementof cities is important to the successof national spatialpolicies.SubSaharan Africa exhibits acute problems of city management in the face of rapid urbanization,albeit from modest bases. Centralizationof decisionmakingin Nigeria,for example,has madeit difficultto dealwith local problems. In very large cities, policiesto limit or stop populationgrowth are not good substitutes for policies that address the urban bias and that directly seek to correct congestionand pollution and provideadequate services.If other citiesare not efficientlyand effectively managed,their chancesof attracting industriesand migrants from the largest urban centers will be small. Regionalpoliciescan strengthen promising secondary urban centers through well-chosen,cost-efficientactions, better policies for transport investment and management, industrial estates policies,and more important, the systematicdevelopmentof organizedinformational networks, such as banking networks, industrial association networks, and better administrative structures, between the secondarycitiesand the capital region. Good city management and selected regional investments,combinedwith national economicpolicies that do not discriminate against rural areas, would do much to alleviatethe problems of urbanization. Urbanization Policy in a Centralized Economy Parish (chapter 6) describes how China's socialistleaders,since their comingto powerin 1949,havetried to shape the nation's cities to avoid many of the urban problems encountered elsewhere in the developing world. Policymakersplannedto restrain the rate of urbanization, since rapid urban growth has often been accompaniedby an insufficientnumber of suitablejobs for new migrants from the countryside.They sought to 8 GeorgeS. Tolleyand Vinod Thomas avoid the pattern found in other countries of rapid growth of a few large coastal cities at the expense of smaller interior cities. In addition,they tried to narrow the significantgapsin livingstandardsbetweenChinese citiesand rural areas bycreating securejobs and guaranteeing such basicservicesas health, education,housing, and essential food supplies for both urban and rural populations. China's history since 1949brings out both the potential and the disadvantagesof urban developmentin a centrally planned economy.With greater control over economicresources than in the averagemarket society, the government was able to shift investment funds to promote the development of medium over large and interior over coastalcities,whichhelpedreduceregional inequalities. Control over jobs and rationed consumer suppliesmeant that for a time the governmentwas able to limit severelythe growth of all cities, and funds that might havebeenspent on an elaborateurban infrastructure for new migrants were spent instead on rapid industrial growth. The government has been able to put the urban populationto work. Mostable-bodiedwomen,andmore than half the urban population,are employed.Fewof the jobs are part-time or likelyto be lost tomorrow;theyare primarily full-time jobs that promise to last for a full career. In these waysChinesecitieshaveavoidedsomeof the severeproblemsof unemploymentand employment instabilitythat have afflictedother developing-country cities. Policy mistakes have, however,been madeand have led to some of the same problemsfound in other societies. For instance, it was an error to downplaythe role of light industryand consumerservices.Somedeveloping-countrycities mayhavetoo many peoplein informal service activities,but China illustratesthe problemsof the opposite extreme. The restricted opportunity for growth of light industry and the bureaucraticrestraints on small individual enterprises have fed problems of youth unemployment.Although elimination of urbanrural income gaps was an objective,on balance a prourban and proindustrial bias might neverthelesshave existed, as in many other countries. The unemploymentproblem was heightened by the rapid expansion of employmentfor women. Jobs were createdduringthe 1960sand 1970s,but since thosejobs were taken almost as frequentlyby women as by men, the needto create additionalopeningswas greater than in other developingsocieties. Furthermore, the rapid expansion of secondary school education, as in many other developingsocieties,contributedto growingnumbers of unemployededucated persons. China avoided this problem at the universitylevelbut not at the secondary level.The unemployedyouths were particularly frustrated because the same level of education had guaranteedgoodjobs just a decadebefore,when education was less common. This frustration-shared with youths in many developingcountries but perhaps felt more acutelyin China becauseof the socialistpromiseof securejobs and rapid development-contributed to the outbreak of petty crime in the 1970s and continues to fuel the social alienation of some youths. China's experience with the virtual elimination of smallinformalserviceactivitiesillustratesthe necessity for these types of activities in developingcities. Some argue that becauseof high populationgrowth rates and the difficultyof centralizedprovisionof essentialurban services,the informalservicesector in poor societiesis essentialand should be embracedrather than shunned. China's leaders seem to be moving closer to that view, which entails a greater relianceon market forces, even though they reject its extreme version. Smaller, more makeshift work arrangements, organized ad hoc by neighborhoodsand individuals,with lower rates of pay and security, are now approvedas a way of providing both employmentand essentialurban services.Further effortsto improvethe relativepositionof rural activities are being made, and farmers are beginning to narrow the gap between averagerural and urban incomes. Concentration and Decentralization Policies At different times and in different countries the growth of large cities has beenwelcomedand deplored. Governmentshave used policy instruments to encourage location in major cities or to foster-sometimes even to force-diffusion. Chapters 7, 8, and 9 examine the reasonsbehind spatiallocationpoliciesin fourcountries and the outcomes of those policies. En couragementof Concentration:Brazil The relativeemphasison concentrationand on decentralization in Brazil has changed with the varying fortunes of the economy;concernabout concentrationhas often diminished during times of economicdifficulty. Neither concentration nor decentralizationmay be undesirable in itself; government policies,however, may have intendedand unintendedeffectson industrial location which affect economicwelfare.In chapter 7 Henderson examines how government policies have influenced concentration in Brazil, and he attempts to evaluate the desirability of such influenceswhen the existence (or absence) of certain types of economiesof scale in urbanization and industrializationis taken into account. Thedata base forthe coreof the paper relatesto 1970,and much of the discussionthereforeconcernsthe An Overviewof UrbanGrowth historical evolution of policieswhich essentiallypromoted concentration. Some aspects of the distinct efforts in the 1970sto achieve decentralizationare covered in chapter 13. Localizationeconomies are found to be strong in Brazil, and therefore agglomeration of firms into specialized cities-to take advantage of such benefits as efficienciesin labor markets and in servicesspecificto an industry and greater specialization among firms within an industry-is advantageous.The present results do not show any significant urbanizationeconomies at the scale of activities prevalent in the urban centers of the South and Southeast of Brazil in 1970. The rationale for effortsto encourage industrialization of the largest urban areas rests on the putative net benefitsfor heavyindustriesfrom locatingin areas with a large general scale of economicactivity.Henderson's findingsdonot, however,supportthis rationale.Rather, they indicatethat effortsto limit or counter decentralization initiativesmay not be desirable. In addition, negative extemalitiesin the form of environmental degradationcould constitute grounds for actuallypromotingsome degreeof decentralization.But the size distribution of Braziliancities is by no means excessivelyskewed,and effortsto bringabout decentralizationor a differentdistributionofcity sizes forits own sake maynot be warranted.Nevertheless,the provision of more uniform incentivesto middle-sizecities-which could simplymean the eliminationof anyspecialincentives, direct or indirect, for larger cities in the southern region-coupled with environmentalrestrictionsin the highly damagedand built-up areas, could lead to an economicallybeneficialdecentralizationof activities. IndustrialMobility and.Decentralization:excessive Cndstr.iaaMoian Lee (chapter 8) documents the changing patterns of employment location in Bogotaand Cali, the first and third largest cities in Colombia,and summarizes some econometricworkon locationchoicesbymanufacturing firms. The studyalso outlines a frameworkfor measuring policyeffectsand drawspolicyconclusions,particularly in the context of Korean experiencewith spatial policy. The main phenomenonobservedis the policymakers' frequent attempts to relocateindustries from the traditional industrial districtsof largecities to outer areas or to smaller cities. The government'splans may include developingnew industrial townsor estates or expanding existing ones to induce new firms or firms that are moving to settle in a desired area. In all cases implementation of such plans and programs requires the selectionof particular typesof industriesto occupysites 9 with particular attributes. Hence it is important for policymakersto understand the requirements of firms for attaining equilibriumat new locationsand to be able to assessthe leveland costsofgovernmentsubsidiesand infrastructure investmentneededto meet such requirements. The Bogota study did not test the effectivenessof explicitpolicyinstruments, partly becausesuch instruments were not implementedin that city. Nevertheless, the behavioralunderpinnings establishedin the study provide clues as to which policy instruments are most appropriatefor influencingboth the location choicesof particular types of firms and the aggregatelocational patterns. It is apparent that government policies intended to influenceemploymentlocationalpattems can be effectiveifthey influencethe site attributeswhich are important to firms. Lee alsoexaminesurban policy in Korea.During the past decadevariousspatialpoliciesto controlthe growth of Seoul and to disperse its populationhave been implemented. For example, in 1971 the greenbelt surroundingSeoulwas established.Subsequentlythe 1977 Industrial LocationAct in effectpreventednew manufacturing firms from locatingwithin Seouland enabled the governmentto issue relocationorders to establishments already set up there. In 1977 the government initiated a ten-yearcomprehensiveplan for redistributing population and industry awayfrom Seoul. Severalother developingcountries havetried to decentralizeeconomicactivityawayfrom the central city. The economic desirabilityof decentralizationpolicies has not beenestablished,andnot much is knownoftheir effects or their welfare implications. The key policy questionis howto guard againstspatialpoliciesthat are in relation to prevalent decentralization trends, since such measures might result in serious welfarelosses.In developingcountriesthe lackofempirical informationon decentralizationand policy effects does not yet permit the formulation of more efficient spatial policies,but policiesto decentralizepopulation and economicactivityare probablynot goodsubstitutes for better intemal management of city growth. For example, the effecton air pollutionor on trafficcongestion of reducing the populationor employmentin a large city by a certain amount is likelyto be small. A DecentralizationProgram: Venezuela Reif(chapter9) uses the caseofVenezuelato providea full-fledgedevaluation of decentralizationpolicy. The goals of Venezuelanpolicy have been to prohibit the location of new manufacturing in Caracasand its surroundings, to induce hazardous industries to relocate 10 GeorgeS. Tolley and Vmod Thomas and to encourageothers to moveto designateddevelopment areas, and to attract new manufacturingplants to the designatedareas. Policyinstruments includedirect financial and fiscal incentives, indirect benefits, and negativeincentivessuch as locationalcontrol. Reiffinds that although little overall deconcentrationtook place from 1971 to 1978, new firms did tend to leave the country's dominant industrial area. It remains to be established,however,that the deconcentration was the result of government policy. An analysis of the effects of financial, fiscal, and negative incentives indicates that these had some, though not major, effects on deconcentration. Reif investigates other factors and hypothesizes,among other things, that firms which receive government support benefit from locationsnear governmentcenters.Aseriesof logit regressions indicates that wages, access to markets, a well-trainedwork force, union activity,and availability of water significantlyaffect firm location decisions,in contrast to the relativelyless significantperformanceof government financial incentives.The work shows that strong economic tendencies must be overcomeif any appreciabledecentralizationis to be achieved. Addressing Urban Problems Part IV of this book contains discussionsof some of the significantproblems that accompanyurbanization. Among the most pressing are management of urban fiscalresources, housing, transport, and environmental protection. of UrbanFinance Management Growing fiscal problems in cities of the developing countries have been caused in part by unprecedented urban growth, for which many countries are illprepared,andby the growingdemandson localservices. The demand for local servicesis sensitiveto increasing population,especiallyof the poor. Positiveincome elasticities for public services and demonstration effects from the developedworld also influencethe demandfor local services.Factors that affect the cost of local services include wages, labor unions, rising land and energy prices, inflation, and the increasing costs of borrowingfunds for large urban infrastructure investments. The major revenuesources-taxes, user charges,and external funding-tend to rise less than expenditures during urbanization,and the result is fiscaland service deficits. One solution to fiscal problemswould be to reassign responsibilityfor urban services from local to central authorities, but Bahl and Linn (chapter 10) do not recommendthis approach.An alternativesolution is to increase local tax authority and make more use of propertytaxes and motor vehicletaxes.Athird solution, also favored, is to encourage reliance on user charges (which have the advantage of being directly linked to services provided). Equity considerations and social costs (for instance,congestion)may,however,keepuser charges low.A fourth solution, to increasefiscaltransfers from centralto localauthorities, has many pros and cons but might be recommendedif proper encouragement to cities can be combined with preservation of local autonomy. Reforms in urban financial arrangements in developingcountries are proceedingslowly; political factors contribute to the inertia. HousingPolicy In developingcountries,housing is a major consumption category;it constitutes, on average,15-25 percent of total urban householdexpenditures.Housing is also one of the most problematic areas in urban development. The most glaring aspectof the problem concerns sprawling squatter areas, delapidated shelter, and appallinglackof basicpublicservices.Other dimensions of the problem are shortages of land, infrastructure services, off-siteservices, amenities, and employment opportunities and the inadequatesupplyand rising cost of housing. For the overwhelmingmajority,housing is privately provided. Public authorities, however, implement licensing,buildingcodes,zoning, and recordkeepingto ensure clarity in property rights. Governmentsalmost universallyhavesome activeinterest in housingfinance. Overt programs of public housing for low-income groups are common. Housing policymust account for people's desires and should maximizeincentivesfor individualsto expandthe housingsupply.Publicinterventions should be limitedto areas where the public sector is best suited to perform, such as direct investment, pricing policy,and regulation. To providehousing requires expertisein many areas. Ingram (chapter 11)stressesthe needforunderstanding the underlying demand for housing. Heanalyzeshousing demand by renters and owners in Bogotaand Cali, Colombia,for 1972and 1978.Hedonicpricecoefficients for housing attributes are used to estimate the cost of a standardizedunit of housing for each workplace,which is then used as the price variableto estimate a demand function for housing that includes other variablesas well. The effectof incomeon the demandforhousing is highlysignificant,and its elasticityis in the upperend of An Overviewof UrbanGrowth the range 0.2-0.8. Price performsless well:its elasticity appears to be less than one. Other variablesinclude age and sex of the householdhead, familysize, and distance to work. Transport influences the rate and pattern of urban developmentand presents multidimensionalissues. Infrastructure in the form of roads and streets is publicly providedbut entails private use. Urban transport planning requires road layout and in some cases provision for commuter rail transit. Theselarge-scaleprojectsare examplesof investmentsthat needrigorous benefit-cost analysis. The planning of transport and other large urban infrastructure investments is complicated not only by income distribution considerationsbut also by the difficultyof taking accountof the feedbackeffectsofinvestments on urban development. If provision of services merely followsdemand, infrastructure may be a bottleneckto development,and developmentopportunities maybe lost. Butif infrastructureleads developmentand, amongother things, fostersnew spatialpatterns, several problems arise. Infrastructure services that do not closelyfollowexisting pattems carry the risk that demand will not materializeas had been projected.As a minimum, benefit-costanalysisof urban projectsmight introduce spatialmodelingto showprobablefuture residential and business locationsand to estimate urban developmentwith and without the proposedproject. Anotheraspect of the urban transport problem is the provision of public transport, which again involvesinteractions betweenpublic and private decisions.In his analysisof public transport Pach6n (chapter 12) points out that private organizationsare responsiblefor most mass transit in Colombia,although local governments grant licensesand route authorizations.Disadvantages can arise from the politicalallocationof routes; examples are parallel routes, duplication of service,and information problems created by the multiplicity of routes. The system is, however,flexibleand appears to be capable of handling the informationproblem. Pach6n gives an economic rationale for preferring small, less capital-intensivevehicles (such as school buses,minibuses,and collectivetaxis)over largemetropolitan buses. The growthin the number of smallbuses in Bogota is a result of lower costs, shorter waiting times, higher trip frequencies, and a greater income elasticityof demandfor small-busservice.The desirability of oldand of newbuses is alsorelevant;an analysisof the age structure, operating costs, and profitabilityof Colombianbuses is provided.Subsidiesthat encourage 11 investments in buses, fare structures that favor new vehicles,and licensingrequirements that restrict vehicle stocks are features of the Colombiansystem. The dependenceon public transport of a large part of the urban population,particularlythe poor, heavilyinfluences fares and services and increases govemment involvement. The Colombian analysis indicates the scopeand problemsofprovidingefficientserviceswithin this framework. UrbanEnvironment Environmental problems are intimately related to urbanizationbecausegrowing pollutionin the developing countries has been caused largely by growth of activityin urban areas. Concem has been heightenedas consciousness about pollution has spread worldwide. Thomas (chapter 13) analyzespoliciesfor dealing with the keytradeoffbetweenreducing environmental damage, on the one hand, and, on the other, payingthe cost of pollutioncontrol and maintainingindustrial competitivenessand growth. In Brazilthe capital and operating costs of air pollution control equipment and spare parts can be used to show how costs of pollution abatement vary among producers. Where effluents per unit of output decline with the size of a firm, it would be advantageousto require less than proportionate abatement for larger producers.An offsettingeffect,however,is economiesof scale in pollution control. The variation in pollution control costs by type and size of firm should be considered in devisingpoliciesthat willachievea givenamount of environmental control at the lowestpossiblecost. The damages to health from the high degree of air pollution in Sao Paulo are largeby any standardsand in comparisonwith the relativelylower risks in outlying areas and in Riode Janeiro. Aregressionofthe mortality rate on the pollutionlevel,populationdensity,per capita income, hospital beds per person, and percentage of people sixty-fiveyears of age and older yieldsa positive and significantcoefficientfor particulates.For example, an annual increaseof one ton of particulatesper square kilometer in the GreaterSao Paulometropolitanarea is associatedwith an increase in mortality of twelvepersons per million. The analysisemphasizesthat benefits from a given amount of pollution reduction in an area will depend on the size of the population. The most advantageoustradeoff between reducing environmentaldamageand maintaining growth can be achievedby a policy that allows industrial and spatial variation in pollution control rather than mandating uniform controls.A promisingapproach is to use emission taxes or pollutionabatementstandards that can be 12 GeorgeS. Tolley and VinodThomas adjusted to conditions in different industries and districts. 2. These estimatesare basedon Davis(1972),vol. 2, p. 51, and on more recent data from the World Bank. Evaluating UrbanProjects Bibliography The findings of this book point to net benefits from selected policy interventions that directly address selected urban problems. In this connection careful evaluations of intended and actual outcomes of urban programs would be helpful. Part of the work would be better evaluations of urban projects, many of which Keae shlter that rigrous rigorous Keare (capte (chapter 14)show 14) shows tha involve shelter. invole evaluation of projects can assist in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of future endeavors in urban policymaking and inproject formulation and implementation. Although much of the paper deals with specific shelter projects financed by the World Bank, the lessons drawn are likely to apply to policymaking as a whole. The projects are evaluated on the basis of eight criteria: project design, the selection of project beneficiaries, construction methods, materials loan programs, housing completion, occupancy, maintenance of housing infrastructure, and community participation. Given a target group of beneficiaries and a policy objective (in this case, shelter), desirable projects are those that strive for efficient resource use through decentralized decisionmaking. Keare stresses market solutions whenever possible and presumes that project participants are the best judges of their own self-interests. In general, projects should provide participants with suitable locations, secure tenure, and adequate credit but beyond these should leave most decisions to the participants. Advantages and disadvantages are associated with construction projects, self-help requirements, housing standards, rentals, and restricted credit policies. The costs of delayed occupancy and inadequate maintenance and the importance of project cost recovery are stressed in this context. Notes 1. Much of the informationin this section is from World Bank (1984). Andors,Stephen.1978."Urbanizationand UrbanGovernment in China's Development:Towardsa Political Economyof Urban Community."EconomicDevelopmentand Cultural Change, vol. 26 (B), pp. 52545. Berry,BrianJ. L., Peter Goheen,and HaroldGoldstein.1971. "Metropolitan Definition: Reevaluation of Internal Concept Practice." In L.AS. Bourne, ed., and StatisticalArea Structure of the City:ReadingsonSpaceand Environment. NewYork: OxfordUniversityPress. Davis, Kingsley. 1965. "The Urbanization of the Human Population." Scientific American, vol. 213 (September), pp. 28, 40. . 1972.WorldUrbanization1950-1970.2 vols.Population MonographSeries4 and 9. Berkeley,Calif.:University of CaliforniaPress. Hauser,Philip M.,and RobertW. Gardner. 1982. "UrbanFuture: Trendsand Prospects."In PhilipM.Hauserand others, eds.,Populationand the UrbanFuture.Albany,N.Y.:State Universityof NewYork. Linn, Johannes F. 1983.Cities in the DevelopingWorld:Policies for Their Equitable and Efficient Growth. NewYork: OxfordUniversityPress. Mills, Edwin S. 1972. "WelfareAspects of National Policy towardCitySizes,"UrbanStudies, vol.9, no. 1, pp. 117-24. Mohan,Rakesh. 1979.UrbanEconomicsand PlanningModels: Assessingthe Potential for Cities in DevelopingCountries. Baltimore,Md.:Johns HopkinsUniversityPress. Renaud,Bertrand. 1981.National UrbanizationPolicy in Developing Countries.NewYork: OxfordUniversityPress. Richardson, Harry W. 1977. City Size and National Spatial Strategiesin DevelopingCountries.WorldBankStaffWorking Paper 252. Washington,D.C. UnitedNations.PopulationDivision.1977.Manual8.Methods for Projectionsof Urbanand Rural Population.Population Studies 55. NewYork. Wheaton,W. C., and H. Shishido. 1979. "UrbanConcentration, AgglomerationEconomiesand the Levelof Economic Development."Working Paper. Cambridge,Mass.:MIT. World Bank. 1984. World DevelopmentReport 1984. New York:OxfordUniversityPress.