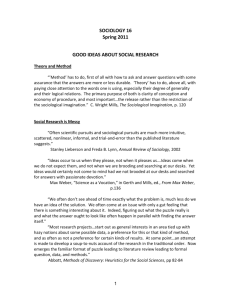

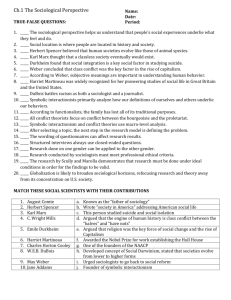

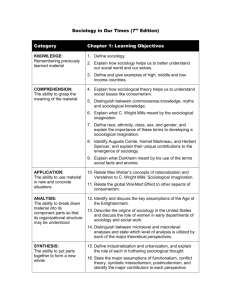

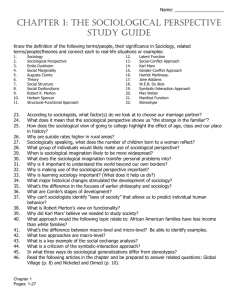

Sociology: A Sociological Compass - Introduction

advertisement