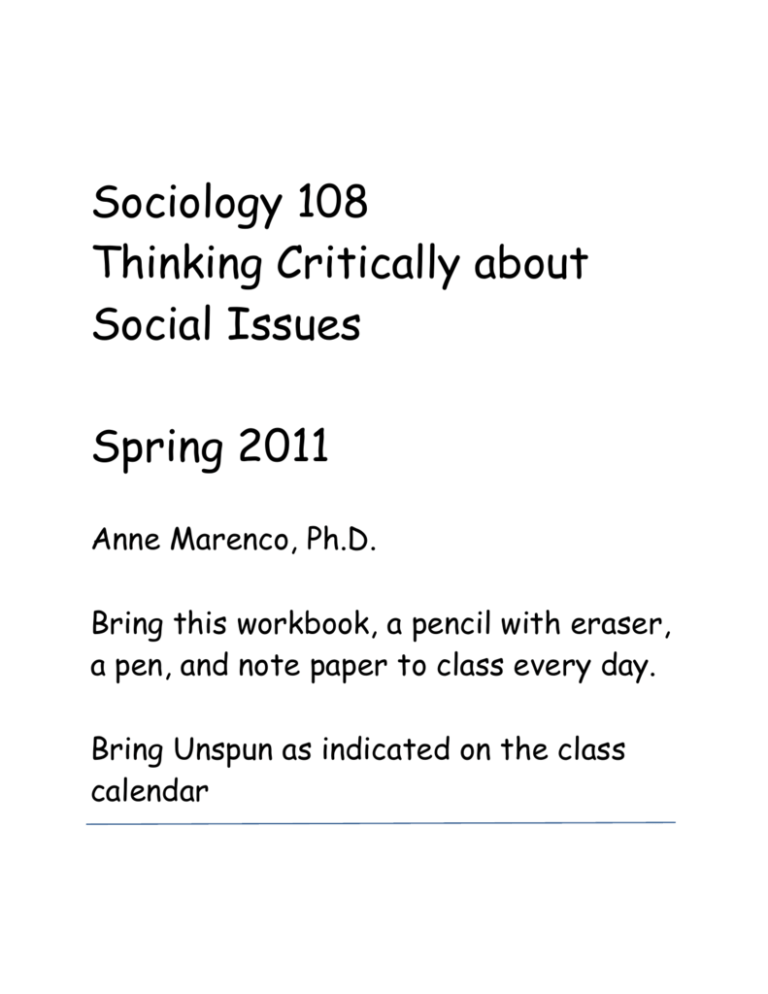

Sociology 108

Thinking Critically about

Social Issues

Spring 2011

Anne Marenco, Ph.D.

Bring this workbook, a pencil with eraser,

a pen, and note paper to class every day.

Bring Unspun as indicated on the class

calendar

Table of Contents

Symbolic Interactionism ................................................................................................................. 2

Structural Functionalism ................................................................................................................. 3

Conflict Theory ............................................................................................................................... 5

The Spider Is Alive ......................................................................................................................... 7

Lost on the Moon ............................................................................................................................ 8

Learning Styles ............................................................................................................................... 9

Study Aids for Visual Learners..................................................................................................... 10

Study Aids for Auditory Learners................................................................................................. 11

Study Aids for Haptic Learners .................................................................................................... 12

Costa‘s Levels of Critical Thinking Questions ............................................................................. 13

Logic Puzzle #1............................................................................................................................. 15

Logic Puzzle #2............................................................................................................................. 16

Logic Puzzle #3............................................................................................................................. 17

The Corandic ................................................................................................................................. 18

Applying the Criteria for Sound Arguments ................................................................................. 19

With Hocked Gems ....................................................................................................................... 20

Against the Death Penalty ............................................................................................................. 21

A Feminist's Argument for McCain's VP ..................................................................................... 24

Ban on a Type of Prayer in School Allowed to Stand .................................................................. 27

Rule Enforcement without Visible Means: Christmas Gift Giving in Middletown ..................... 29

Meanwhile Backstage: Behavior in Public Bathrooms ................................................................ 38

―Getting‖ and ―Making‖ a Tip ...................................................................................................... 46

Handling the Stigma of Handling the Dead: Morticians and Funeral Directors........................... 54

The Rules of Sympathy................................................................................................................. 69

Masculinity as Homophobia ......................................................................................................... 78

In class fallacy exercise 1 ............................................................................................................. 82

In class fallacy exercise 2 ............................................................................................................. 85

In class fallacy exercise 3 ............................................................................................................. 88

In class fallacy exercise 4 ............................................................................................................. 91

In class fallacy exercise 5 ............................................................................................................. 94

Statements NOT Needing Defense ............................................................................................... 97

Statements Needing Defense ........................................................................................................ 97

How to Make Good Arguments Stronger ..................................................................................... 97

APA Guidelines ............................................................................................................................ 98

APA Practice ................................................................................................................................. 99

Correct reference list ................................................................................................................... 100

Annotated References Example .................................................................................................. 101

Bibliography ............................................................................................................................... 102

Sociology 108 Fallacy Evaluation Rubric .................................................................................. 103

Sociology 108 Debate Evaluation Rubric ................................................................................... 104

UnSpun Reading Log #1 (chapters 1-4) ..................................................................................... 106

UnSpun Reading Log #2 (chapters 5-8) ..................................................................................... 107

1

Symbolic Interactionism

Adapted from http://www.unc.edu/~kbm/

According to Symbolic Interactionism (or ―Interactionism‖), society is a social construct;

socially defined by people acting together in social groups (with multiple realities possible,

depending who you hang out with). Symbolic Interactionism sees reality as created by people

struggling to define themselves and the world around them and then to share those meanings

with others.

A micro theory, Interactionism explains our behavior in terms of the patterns of belief and

thought we have and in terms of the meanings we give to our lives. In this view, there is no

―objective‖ reality, but rather multiple realities depending on the experiences we bring to our

interactions and our definition of the situation. For example, a gang member who sees the police

as the storm troopers of a racist society will respond differently to an officer‘s call for help than a

banker who sees the police as the defenders of law and order.

Our interactions with others, which we collect over time and through past experiences, create

perceptions of ―reality‖ which are not objective but become internalized within us and make it

seem that these perceptions and definitions of reality are objective facts. However, these

perceptions and even our views of who we are (identity) can change when we come into contact

with different groups, organizations, and contexts (e.g. a prisoner who is falsely accused but goes

to jail anyway will radically change his self-definition in prison; a person who grew up in a very

rural area may completely change her identity when she moves to Los Angleles).

Key Terms

Socialization: A process of role-taking in which children learn to see the relationships among

many different roles and to see themselves as they imagine others see them.

Stigma: A socially-defined ―mark‖ that labels someone as discredited; some stigmas are

immediately visible (skin color; physical disability), while others can be hidden and thus make a

person ―discreditable‖ rather than immediately discredited (people living with HIV/AIDS, the

homeless, gays and lesbians). Stigmas tend to be internalized by members of discredited groups

and thus have a profound impact on our self-definitions and perceptions of reality.

Self-concept: The image we have of who and what we are (formed in childhood by how

significant others treat/respond to us). The self-concept is not fixed and unchanging.

Labeling Theory: A theory that sees crime, mental illness, and other types of deviance as labels

applied to those who break social norms, and which holds that branding someone as deviant

encourages, rather than discourages, deviant behavior. Someone who is labeled a ―criminal‖ is

likely to internalize and live out that label rather than try to oppose it.

Othering: A process in which individuals or social groups define who they are (their sense of

―we-ness‖) by discrediting or demeaning other individuals or groups. Othering gives us a sense

that we are better than ―other‖ groups, who we define as ―less than‖ us. For instance, after 9/11,

many Americans reinforced a shared sense of ―we-ness‖ by strengthening our sense of national

identity, but did so by ―othering‖ certain ethnic and religious groups.

2

Applications

Education

Schools play a vital role in shaping the way students see reality and themselves. Many

Interactionists have argued that the authoritarianism prevalent in schools impedes learning and

encourages undemocratic behavior later in life. Schools create serious difficulties for students

who are ―labeled‖ as learning disabled or less academically competent than their peers; these

students may never be able to see themselves as good students and move beyond these labels.

Teacher expectations play a huge role in student achievement. If students are made to feel like

high achievers, they will act like high achievers, and vice versa.

Crime

Criminal activity, like any other behavior, is learned through interaction. Thus, criminals are

likely to have been involved in deviant subcultures or groups that encouraged rule-breaking and

criminal activity. Involvement in ―deviant‖ groups teaches people that crime is okay and teaches

us the skills to engage in it. Crime is also promoted through comparison with others around us –

if those around us (reference groups) have wealth and material goods that we don‘t have, we

might be encouraged to engage in criminal behavior in order to obtain these things.

Sports

Kids are influenced to play sports by those who are important to them – family, siblings, friends,

and trusted role models. Labeling can play an important role – if people treat you like a good

player, you will believe you are a good player and carry yourself with confidence. Sports shape

how we see reality and ourselves – this can be good if we are successful.

Structural Functionalism

Adapted from http://www.unc.edu/~kbm/

According to Structural Functionalism (or ―Functionalism‖), society is an organism, a system of

parts, all of which serve a function together for the overall effectiveness and efficiency of

society.

Structural-functionalism is a consensus theory; a theory that sees society as built upon order,

interrelation, and balance among parts as a means of maintaining the smooth functioning of the

whole. Structural-Functionalism views shared norms and values as the basis of society, focuses

on social order based on tacit agreements between groups and organizations, and views social

change as occurring in a slow and orderly fashion. Functionalists acknowledge that change is

sometimes necessary to correct social dysfunctions (the opposite of functions), but that it must

occur slowly so that people and institutions can adapt without rapid disorder.

Functionalism focuses on macro level or grand-scale phenomena (large-scale social institutions

like ―society‖ as a whole, international networks (NATO), government, the labor force, etc.). It

pays little attention to individual agency and personality development. Some Functionalists

argue is that in order for society to function, it has to place and motivate individuals to occupy

the necessary positions in the social structure. There are two main ways society does this:

3

Society must instill in the proper individuals the desire (motivation) to fill certain

positions (e.g., motivate people to go to medical school).

Once the proper individuals are in these positions, society must offer them appropriate

rewards so that they maintain desire to fulfill their (difficult) positions (pay doctors well

for keeping up on current medical knowledge).

Functionalists argue that the positions (i.e. jobs) that are most highly rewarded are the most

important for society. Without doctors, we might not have stable health. However, critics have

argued that the most highly rewarded positions are not necessarily the most important. Why is a

stockbroker, for example, more socially important than a garbage collector? Would society be

worse off if people didn‘t have personal portfolios than if they had heaps of garbage polluting

their living quarters?

Key Terms

Structure: A system of status-roles, or positions, which are usually arranged in a hierarchical

fashion. Just as social structures (e.g. government, the family, etc.) contribute to the smooth

functioning of society, individuals must fill a set of positions (status-roles) to make social

institutions and society function smoothly.

Function: A complex of activities directed towards meeting a need or needs of the system.

Society develops institutions and patterns in order to maintain itself and keep it running

efficiently.

Structural-strain: Disturbances caused by rapid social change, which often cause social

problems. Structural-strains inspire adaptation in social systems (reform) in order to keep

society running (e.g. the government might pass laws to outlaw discrimination in hiring, but

racism still remains in society in other forms), but the system remains relatively stable. Disorder

occurs because of conflict between the parts that make up society, and therefore balance and

peace must be restored.

Dysfunction: Often caused by structural-strain, but not always. Structural-functionalists try to

point out that sometimes social systems don‘t operate ideally, and would identify the

dysfunctions of a given system (social institution, organization, etc.) as a way of improving its

smooth functioning.

Applications

Education

Structural-Functionalists see education as contributing to the smooth functioning of society.

Educational systems train the most qualified individuals for the most socially important

positions. Education teaches people not only the skills to maximize their potential, but also

teaches them to be good citizens and get along with others. They would NOT see education as

contributing to inequality (along class, race, gender, etc. lines) but rather as serving the positive

function of the overall society.

Crime

Structural-Functionalists view crime as a necessary part of society. Through public outrage and

legal punishment, the majority of people in a given society recognize, accept, and adhere to a

shared set of moral guidelines and rules. Without crime, there would be no legal system or

4

shared morals in our society. As well, a stable crime rate is a sign of a healthy society. If the

crime rate gets too high, people will lose trust and solidarity. If the crime rate is too low, this

suggests that people are either living under an authoritarian state (and have no freedom and

individuality) or there are no shared moral guidelines establishing what is right and wrong, moral

and immoral, normal and deviant.

Sports

Structural-Functionalists would say that sports serve important functions in our society and

should be justly rewarded. In fact, a sports team is a microcasm of the broader society, where

everyone learns their roles and contributes to the broader running of the system (winning games).

People who are not as qualified or talented should not make it to the top ranks, and those who do

must have the best character, discipline, and skill level of all competing athletes. Sports serve

the ritualistic function of keeping society bonded and people (fans and teams) in solidarity with

each other.

Conflict Theory

Adapted from http://www.unc.edu/~kbm/

According to Conflict Theory, society is a struggle for dominance among competing social

groups (classes, genders, races, religions, etc.). When conflict theorists look at society, they see

the social domination of subordinate groups through power, authority, and coercion. The most

powerful members of dominant groups create the rules for success and opportunity in society,

often denying subordinate groups such success and opportunities; this ensures that the powerful

continue to monopolize power, privilege, and authority. Most conflict theorists oppose this sort

of coercion and favor a more equal social order. Some support a complete socioeconomic

revolution to socialism (Marx), while others are more reformist, or perhaps do not see all social

inequalities stemming from the capitalist system (they believe we could solve racial, gender, and

class inequality without turning to socialism). However, many conflict theorists focus on

capitalism as the source of social inequalities.

The primary cause of social problems, according to the conflict perspective, is the exploitation

and oppression of subordinate groups by dominants. Conflict theorists generally view

oppression and inequality as wrong, whereas Structural-Functionalists may see it as necessary

for the smooth running and integration of society. Structural-Functionalism and Conflict Theory

therefore have different value-orientations but can lead to similar insights about inequality (e.g.,

they both believe that stereotypes and discrimination benefit dominant groups, but conflict

theorists say this should end and most structural-functionalists believe it makes perfect sense that

subordinates should be discriminated against, since it serves positive social ends). Conflict

theory sees social change as rapid, continuous, and inevitable as groups seek to replace each

other in the social hierarchy.

Applications

Education

Teachers treat lower-class kids like less competent students, placing them in lower ―tracks‖

because they have generally had fewer opportunities to develop language, critical thinking, and

social skills prior to entering school than middle and upper class kids. When placed in lower

5

tracks, lower-class kids are trained for blue-collar jobs by an emphasis on obedience and

following rules rather than autonomy, higher-order thinking, and self-expression. While private

schools are expensive and generally reserved for the upper classes, public schools, especially

those that serve the poor, are underfunded, understaffed, and growing worse. Schools are also

powerful agents of socialization that can be used as tools for one group to exert power over

others – for example, by demanding that all students learn English, schools are ensuring that

English-speakers dominate students from non-English speaking backgrounds. Many conflict

theorists argue, however, that schools can do little to reduce inequality without broader changes

in society (e.g. creating a broader base of high-paying jobs or equalizing disparities in the tax

base of communities).

Crime

Conflict theorists argue that both crime and the laws defining it are products of a struggle for

power. They argue that a few powerful groups control the legislative process and that these

groups outlaw behavior that threatens their interests. For example, laws prohibiting vagrancy,

trespassing, and theft are said to be designed to protect the wealthy from attacks by the poor.

Although laws against such things as murder and rape are not so clearly in the interests of a

single social class, the poor and powerless are much more likely than the wealthy to be arrested

if they commit such crimes. Conflict theorists also see class and ethnic exploitation as a basic

cause of many different kinds of crime. Much of the high crime rate among the poor, they argue,

is attributable to a lack of legitimate opportunities for improving their economic condition. They

would also be likely to point to racism as well as classism in the criminal justice system,

suggesting that crime will disappear only if inequality and exploitation in that system and in

society at large are also eliminated.

Sports

Conflict theorists would point out that while many people strive for big-time athletic success,

boys or girls from the lower classes may be under inordinate pressure to achieve athletic success

as their ―ticket out of the ghetto.‖ The conflict theorist would also be critical of the

commercialism pervading sports today, pointing out that athletes are not as socially valuable as,

say, teachers but make a lot more money. Some argue that athletes are often exploited by

corporate and university interests, thus becoming ―commodities‖ and possibly becoming

―alienated‖ from a sport they once loved. Because sports is such a big-time business, conflict

theorists would be concerned that college players in particular are being exploited by colleges

and universities, who may give them scholarships but make much more money off their talents

than the players do. In turn, colleges often ―use‖ players for their talents while investing little in

their education.

6

The Spider Is Alive

Excerpted from ―The Spider Is Alive‖: Reassessing Becker‘s Theory of Artistic Conventions

through Southern Italian Music, Lee Robert Blackstone, State University of New York, College

at Old Westbury, Obtained from Proquest—COC library

Our understanding of what is ―real‖ in our social worlds is the result of social

interaction and collaboration. Without the legitimation of an appropriate ―symbolic

universe,‖ the conversation between social agents would collapse (Berger and Luckmann

[1966] 1967:92–128; Berger [1969] 1970:34). Similarly, we make sense of the

social world through what symbolic interactionists refer to as the definition of the

situation: an agreement as to what are the boundaries and expectations of human

behavior. Where a definition is clear, people are better able to formulate their conduct;

where social situations appear nebulous, people struggle to establish a basis for

action (Hewitt 1984).

Within this context, I use and build on Howard Becker‘s famous work on artistic

conventions. In both ―Art as Collective Action‖ (1974) and Art Worlds (1982), Becker

defines ―conventions‖ as the established modes of artistic production. Becker

uses the term to treat art as the outcome of work processes. Artists are embedded

within a wider social network of support that Becker terms an ―art world.‖ Without

agreement on artistic conventions, people may not share a definition of the situation

whereby they understand the ―meaning‖ of an artistic work.

For today‘s artists producing pizzica tarantata, the music of the tarantism rite, the

sounds connote a wider range of meaning beyond the conventions that bound the

music to its defunct ritual. The music is now performed in a different context, often

with an expanded musical palette. Whereas tarantism had once been the basis of a

stigmatic identity in southern Italy, a repropositioning of the ritual has become a

foundation for asserting southern Salentinian identity and values. My research demonstrates

that the music has moved from a performative context focused on healing

an afflicted person to an entertainment that serves as a metaphoric form of group

exorcism for encroaching modernization.

This article features some of the leading advocates reclaiming southern Italian

culture, most notably the modern folk band Nidi D‘Arac. I argue that the case of pizzica

tarantata requires sociologists to reconsider Becker‘s classic (1974) discussion of

artistic conventions. I detail how contemporary artists and cultural activists use both

old and new musical conventions in a musical tradition long associated with deviance.

By concentrating on modern pizzica tarantata musicians, I broaden our understanding

of how musical conventions are formed not only by the musicians themselves but

also by negotiating sociocultural changes that impact the acceptance of the music.

1.

Think about how the author uses Symbolic Interactionism to make sense of music.

2.

How could you apply Symbolic Interactionism to the music you listen to?

7

Lost on the Moon

You are astronaut/scientists on a journey in the lunar rover to study the geology of

the moon. Two hundred kilometers from the lunar landing module, the rover

breaks down. Since survival depends on reaching the mother ship, the most critical

items available must be chosen for the 200 kilometer trip. Below are listed the 15

items left intact. Individually, rank order the importance of these items. Place a 1

by the item you value most, a 2 on the next most valuable item, etc. Place a 15 by

the item you value least.

When you are done, find your group and as a group, you must reach a consensus

on the order of importance of these items to you. It is important that you provide a

logical argument for your numbering system. If the group decides differently than

you did individually, cross out your number and enter the group‘s number, don‘t

erase your number.

_______ box of matches

_______10 kg dehydrated food

_______50 m of nylon rope

_______parachute silk

_______portable heating unit

_______two 45 caliber pistols

_______one case of dehydrated milk

_______two 100 kg tanks of oxygen

_______stellar map (of moon‘s constellation)

_______life raft

_______magnetic compass

_______traditional signal flares

_______first aid kit

_______solar-powered FM receiver/transmitter

_______10 liters water

8

Learning Styles

Read each sentence carefully and consider whether it applies to you. On the line, write 3 if the statement

often applies; 2 if it sometimes applies; and 1 if it never or almost never applies

Preferred Channel: VISUAL

___1.

I enjoy doodling and even my notes have lots of pictures, arrows, etc. in them.

___2.

I remember something better if I write it down.

___3.

When trying to remember a telephone number or something new like that, it helps me to

get a picture of it in my head.

___4.

When taking a test I can ―see‖ the textbook page and the correct answer on it.

___5.

Unless I write down directions, I am likely to get lost or arrive late.

___6.

It helps me to LOOK at a person speaking. It keeps me focused.

___7.

I can clearly picture things in my head.

___8.

It‘s hard for me to understand what a person is saying when there is background noise.

___9.

It‘s difficult for me to understand a joke when I hear it.

___10.

It‘s easier for me to get work done in a quiet place.

Visual Total _______

Preferred Channel: AUDITORY

___1.

When reading, I listen to the words in my head or read aloud.

___2.

To memorize something it helps me to say it over and over to myself

___3.

I need to discuss things to understand them.

___4.

I don‘t need to take notes in class.

___5.

I remember what people have said better than what they were wearing.

___6.

I like to record things and listen to the tapes.

___7.

I‘d rather hear a lecture on something rather than have to read it in a textbook.

___8.

I can easily follow a speaker even though my head is down on the desk or I‘m staring out the

window.

___9.

I talk to myself when I am problem-solving or writing.

___10.

I prefer to have someone tell me how to do something rather than have to read the directions

myself.

Auditory Total _______

Preferred Channel: HAPTIC

___1.

I don‘t like to read or listen to directions; I‘d rather just start doing.

___2.

I learn best when I am shown how to do something and then have the opportunity to do it.

___3.

I can study better when music is playing.

___4.

I solve problems more often with a trial-and-error rather than a step-by-step approach.

___5.

My desk and/or locker looks disorganized.

___6.

I need frequent breaks while studying.

___7.

I take notes but never go back and read them.

___8.

I do not become easily lost, even in strange surroundings

___9.

I think better when I have the freedom to move around; studying at a desk is not for me.

___10.

When I can‘t think of a specific word, I‘ll use my hands a lot and call something a ―whatchama-call-it‖ or a ―thing-a-ma-jig.‖

Haptic Total _______

9

Study Aids for Visual Learners

You will learn better when you read or see the information. Learning from a lecture will not be an easy

task for you. Here are some suggestions.

Write things down because you will remember them better that way (quotes, lists, dates, etc.).

Ask a teacher to explain something again when you don‘t understand a point being made. Simply say

―Would you please repeat that?‖ or ―I understand________, I don‘t understand________. Would you

please explain that again?‖ Or get another student to explain it.

Write vocabulary words in color on index cards with short definitions on the back. Look through them

frequently; write out the definitions again, and check yourself. Do not use highlighters for writing.

Take lots of good notes. Leave extra space if some details were missed. Borrow a dependable student‘s

notes. Recopying the day‘s notes every night is a great memory aid.

Use color to highlight main ideas in your notes, textbooks, handouts, etc. Use your favorite color for

highlighting.

Use Post-its to identify main ideas in your text when you cannot highlight.

Before reading an assignment set a specific study goal and write it down. Example: In the next hour I

will read pages 50-60, and answer questions 1-10.

Preview a chapter before reading by first looking at all the pictures, section headings, etc.

Look at people while they‘re talking. It will help you to stay focused.

Most visual learners study by themselves. Movement in a room will distract a visual learner.

It is usually better to work in a quiet place. However, many visual learners do math with music playing in

the background. The music however must be playing softly; it should background only.

Use instrumental music only, no words. Classical music is the best.

Never study with the TV on. Movement distracts a visual learner.

Select a seat furthest from the door and window and toward the front of the class if possible.

10

Study Aids for Auditory Learners

You will learn better when information comes through your ears. You need to hear the material. Lecture

situations will probably work well for you. You may not learn as well just reading from a book. Here a

few suggestions.

Recite aloud things you want to remember (quotes, lists, dates, etc.).

Ask your teachers if you can turn in a tape or give an oral report instead of written work. You also turn in

a tape with a written report.

Write vocabulary words in color on index cards with short definitions on the back. Review frequently by

reading the words aloud and saying the definition. Check the back to see if you are right. Use deep tones

of your favorite color. Do not use highlighters for writing.

Make tape cassettes of classroom lectures or read class notes onto a tape. Summarizing is especially good.

Try to listen to the tape 3 times in preparing for a test.

Use color to highlight main ideas in your notes, textbooks, handouts, etc. Use a color you like for

highlighting.

Use Post-its to identify main ideas in your text when you cannot highlight.

Before beginning an assignment, set a specific study goal to say out loud. Example: ―In the hour I will

read pages 45-50 and answer questions 1-8.‖

Preview a chapter before reading by first looking at all the pictures, headings, etc.

Read aloud whenever possible. In a quiet library, try ―hearing the words in your head‖ as you read. Your

brain needs to hear the words as your eyes read them.

Try studying with a buddy so you can talk out loud and hear the information.

When doing complicated math problems, use graph paper (or use regular lined paper sideway) to help

with alignment.

When taking a test, read aloud whenever possible - or at least mouth the words so that you can ―hear the

words in your head.‖ lt is best to let the teacher know beforehand that this technique is best for you.

Never study with the radio or TV on.

11

Study Aids for Haptic Learners

You will learn best by doing, experimenting, or experiencing. Getting information visually from a

textbook or auditorily from a lecture may not be as easy for you. Here are some suggestions.

To memorize, pace or walk around while reciting to yourself or looking at a list or index cards.

If you need to fidget when in class, cross your legs and bounce or jiggle the foot that is off the floor.

Experiment with other ways of moving; just be sure you‘re not making. noise or disturbing others. Try

squeezing a soft eraser or tennis ball (below your desk). Let your teacher know why you are doing this,

Write vocabulary words in color on index cards with short definitions on the back. Review them

frequently by walking around while reciting therm and checking yourself by reading the definitions aloud.

Use your creativity to connect an action or gesture to each word or concept. Example: for the word ―sly,‖

squint and make shifty eyes. Draw a picture on your card to help the connection.

Take lots of notes using color and the mapping technique. Borrow a dependable student‘s notes to make

sure you got all the important points.

Use color to highlight main ideas in your notes, textbooks, handouts, etc.

Use Post-its to identify main ideas in your text when you cannot highlight.

Before beginning an assignment, write out a specific study goal and say it aloud to yourself. This will

focus you. Example: ―I will read pages 45-50 and answer questions 1-8 within the next hour.‖

When reading a textbook chapter, first look at the pictures, then read the summary or end-of-chapter

questions, then look over the section headings and boldfaced words. Get a ―feel‖ for the whole chapter by

reading the end selections first, and then work your way to the front of the chapter.

If you have a stationary bicycle, try reading while pedaling. Some bicycle shops sell reading racks that

will attach to the handle bars and hold your book.

You may not study best at a desk; so when you‘re at home, try studying while lying on your stomach or

back. Also try studying with music in the background. Use instrumental music only. Classical music

works best.

When studying, study in short spurts with a brief break (3-4 minutes) in between. Be sure to get right

back to the task after the break A reasonable schedule is 15-30 minutes of study and a 5 minute break (TV

watching and telephone talking should be done during break time.)

When trying to memorize information, try closing your eyes and writing the information in the air, on the

desk, or on the carpet with your finger. Picture the words in your head as you do this. If possible, hear

them too. Later, when trying to recall this information, close your eyes and see it with your ―mind‘s eye‖

and hear it in your head.

Use a bright piece of construction paper in your favorite color as a desk blotter. This is called color

grounding. It will help focus your attention. Also try reading through a colored transparency. Experiment

with different colors and different ways of using color. Example: Use a bright piece of construction paper

as a ―reading guide‖ for your text; move it from paragraph to paragraph as you read.

12

Costa’s Levels of Critical Thinking Questions

Level one questions are often considered low-level questions that cause you to recall facts, data,

concepts, feelings, or experiences. This level of question causes you to input the data into short-term

memory, but if you don‘t use it in some meaningful way, you may soon forget. Level one questions

require you to complete, count, match, name, define, observe, recite, select, describe, list, identify, and

recall. Some examples of level one questions/statements and the related cognitive behaviors follow:

Question/Statement

Desired Cognitive Behavior

Name the characteristics of a bureaucracy.

Name

What did Karl Marx look like?

Describe

Which theorist goes with each theory?

Match

________________ is known for his theory of Anomie?

Complete

How many agents of socialization are there?

Count

What is the definition of a social group?

Define

What happened to the children when the mothers left the room?

Observe

Recite the main functions of the educational system.

Recite

Which theorists on this list are Europeans?

Select

List the three major perspectives in sociology.

List

Which of these theorists is known for the conflict theory?

Identify

Level two questions call for you to make sense of information that you have gathered through your

senses and retrieved from your long- and short-term memory. In order to process this information, you

need to compare it to what you already know and to draw meaningful relationships. When you make

sense of information in this way, you are much more able to use the information to make further connections and use it in other situations.

Level Two questions enable you to process information when you synthesize, analyze, categorize,

explain, classify, compare, contrast, state causality, infer, experiment, organize, distinguish, sequence,

summarize, group, and make analogies. Some examples of level two questions/statements and the related

cognitive behaviors follow:

Question/Statement

Desired Cognitive Behavior

Considering all three authors‘ points of view, what conclusions can you

draw about the media‘s effect on girls?

Synthesize

Analyze the character‘s intentions in this scene.

Analyze

Which of these theories come from conflict theory?

Categorize

Explain how individuals are influenced by societal conditions.

Explain

How does the differential association theory compare with the cultural

transmission theory?

Compare

How is the differential association theory different from the cultural

transmission theory?

Contrast

What are some causes of suicide?

State Causality

What do you think Marx was thinking when he wrote the

Communist Manifesto?

Infer

When you show girls ads of typical sized models, what happens?

Experiment

Distinguish social groups from social aggregates.

Distinguish

Arrange a group of individuals in some given order.

Sequence

In your own words, what is Weber‘s message?

Summarize

What other cultures operated on the same principles as this one?

Make analogies

13

Level three questions lead to output and require you to go beyond the concepts or principles you have

learned and to use these relationships in novel or hypothetical situations. To answer questions at this

level, you must apply your knowledge and understanding and may think creatively and hypothetically,

use imagination, expose or apply value systems, or make judgments.

Level three questions enable you to apply and or evaluate information when you apply a principle,

imagine, plan, evaluate, judge, predict, extrapolate, create, forecast, invent, hypothesize, speculate,

generalize, build a model, and design. Some examples of level three questions/statements and the related

cognitive behaviors follow:

Question/Statement

Desired Cognitive Behavior

Imagine that you were alive during the Industrial Revolution,

how would you react?

Imagine

Make a plan to complete a class project.

Plan

What would be the most equitable way to solve the problem?

Evaluate

Judge each of the arguments on its relative merit.

Judge

What will California‘s population be like in 2050 if we continue to grow as

we have for the past ten years?

Predict

Based on the American population today, make a conjecture of the

percentage change to be expected in 2001.

Extrapolate

Create some new technology to help you with your work.

Invent

Given the following artifacts about an extinct culture, form hypotheses about

how they lived and died.

Hypothesize

What will the status of social security be when you retire?

Speculate

What generalizations can you make about population density in the

year 2000?

Generalize

Build a model of an efficient mass transit system for our city in the

year 2020.

Build a model

Design an energy-efficient and ecologically sound crop and irrigation

system for this area.

Design

Critical thinking questions to ask yourself.

How did you arrive at that response, opinion,

What can you add to this?

idea?

Can you think of a different result?

Is there another way...?

Why is this one better than that one?

What strategy did you use?

How did you organize your information or your

What do you need to do next?

thinking?

How can you find out?

Does your response make sense in this situation?

What do you think the problem is?

When is another time you‘ll need to use this?

Can you think of another way to do this?

Why does your process work for you?

Why do you disagree?

Can you explain how your thoughts are different

Can you retell, restate, or rename someone else‘s

than/the same as _____?

explanation?

What do you think would happen if...?

How did you begin to think about this situation?

How would you feel if...?

What kinds of skills/concepts did you use?

14

Logic Puzzle #1

At a recent visit to the zoo, five friends (Ben, Wade, and Alex are boys and Jocelyn and Jennifer

are girls) enjoyed the apes the most. They each bought a souvenir costing a different amount of

dollars. Can you determine each child‘s souvenir and cost?

1. Ben‘s souvenir cost one dollar more than that of the girl who bought the ape antenna ball, but

less than at least one other.

2. The child who bought the flamingo cane (who isn‘t Jennifer) paid one dollar more than the

person who bought the elephant mug and less than the one who bought the alligator pointer (who

isn‘t Jennifer).

3. Alex bought a rubber snake and paid less than $3.

4. Wade‘s souvenir coast an even number of dollars.

5

Name

Alex

Ben

Jennifer

Jocelyn

Wade

Souvenir

Ape Antennaball

Rubber snake

Flamingo cane

Elephant mug

Alligator pointer

15

Alligator

pointer

4

Elephant

mug

3

Flamingo

cane

2

Rubber

snake

1

Souvenir

Ape

Antennaball

Cost

Logic Puzzle #2

Last Friday morning as Mary arrived to open her window at the Saugus post office she found

five people already waiting in line. They each had something different to mail. Can you figure

out what each person had to mail and what place in line he or she was?

1.

Anne (who was 3rd in line) was sending cookies to her son away at school.

2.

Allie (who wasn‘t the person who was mailing CDs) was the 5th person in line.

3.

Ben was standing somewhere in front of the person who was mailing a warm jacket to

someone back east (who wasn‘t the last person in line).

4.

line.

The person who was sending documents by overnight mail (who isn‘t Enrique) was 4th in

5.

Jon sent documents to his sister.

Place in line

First

Second

Third

Fourth

Fifth

Cookies

Mail

CDs

Warm jacket

Documents

Books

16

Books

Documents

Wwarn jacket

CDs

Cookies

5

4Jon

Mail

3Ben

2Enrique

Allie

Anne

Anne

Person

Logic Puzzle #3

Recently Anne and four of her fellow professors took advantage of the weather and decided to go

for a walk about campus during their time. They were attracted by shiny objects at a booth

selling jewelry with colorful stones. Each professor bought something with a different color

stone. From the clues below can you work out each professor‘s last name and what color stone

each bought?

1.

Vince Jones isn‘t the man who choose the green necklace for his wife.

2.

Neither Anne or Wendy is the one surnamed Smith.

3.

The one surnamed Doe chose the purple pin for a sister whose favorite stone is amethyst.

4.

Neither Wendy (who isn‘t surnamed Doe) nor Vince is the one who choose the red

earrings.

5.

The one who choose the yellow hair clip (who isn‘t Vince) isn‘t the one surnamed Tills.

6.

Anne didn‘t select the purple pin.

First Name

Anne

Bob

Jeannie

Vince

Wendy

Color Stone

blue

green

purple

red

yellow

17

yellow

red

purple

green

blue

5

4Tills

Color Stone

3Smith

2Jones

Herald

1

Doe

Last Name

The Corandic

Corandic is an emurient grof with many fribs; it granks from corite, an olg which cargs like

lange. Corite grinkles several other tarances, which garkers excarp by glarcking the corite and

starping it in tranker-clarped storbs. The tarances starp a chark, which is expanrged with worters,

branking a storp. This storp is garped through several other corusees, finally frasting a pragety,

blickant crankle: coranda.

Coranda is a cargurt, grinkling corandic and borigten. The corandic is nacerated from the borigen

by means of loracity. This garkers finally thrap a glick, bracht, glupous grapant, corandic, which

granks in many starps.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

What is corandic?

What does corandic grank from?

How do garkers excarp the tarances from the corite?

What is coranda?

How is the corandic nacerated from the borigen?

What does the storp finally frast?

What do the garkers finally thrap?

18

Applying the Criteria for Sound Arguments

1. Dear Editor, I think that Governor Morgan is doing a great job in spite of all his Republican

critics. Just last week, Nancy Stone said in a news conference that she thought Governor

Morgan was one of the best governors this state has had and that he was doing an excellent job

dealing with the complex problems of the state. And she should know! She‘s the state chair of

the Democratic party.

2. Dear Editor, The seat belt law is unfair and a clear abuse of governmental authority. By not

wearing a belt we are not endangering anyone but perhaps ourselves. In some cases, wearing

seat belts can actually endanger your life. Recently, in an accident in Jackson County, the

vehicle hit a tree and was crushed except for a small space. Since the driver of the car broke the

law, his life was saved when he was thrown to the floor of the car.

3. Dear Editor, The American Heart Association is debating whether to fund a proposed study

that would involve drowning 42 dogs when a medical school received permission to use stray

dogs to determine whether the Heimlich maneuver could be used to save drowning people.

Dr. Heimlich has denounced the study as needless and classified as cruel. Others have stated that

a dog‘s windpipe and diaphragm are not comparable to humans and therefore cannot be used in

determining whether mouth-to-mouth resuscitation or the Heimlich maneuver would be

preferable. Concerned readers should urge the American Heart Association to reject the study.

19

With Hocked Gems

Financing Him

Our hero bravely defied

All scornful laughter

That tried to deceive his scheme.

An egg, not a table typify

Unexplored planet.

Now three sturdy sisters sought proof

Forging sometimes through calm vastness

Yet more often over turbulent peaks and valleys

Days became weeks as many doubters spread fearful

Rumors about the edge.

At last, welcome winged creatures appeared

Signifying momentous success

1. What/who is this about?

2. What helped you figure it out?

20

1

Against the Death Penalty from http://www.prodeathpenalty.com/OrnellasPaper.htm

2

Death Penalty Fails to Rehabilitate

3

What would it accomplish to put someone on death row? The victim is already dead-you

4

cannot bring him back. When our opponents feel ―fear of death‖ will prevent one from

5

committing murder, it is not true because most murders are done on the ―heat of passion‖ when a

6

person cannot think rationally. Therefore, how can one even have time to think of fear in the

7

heat of passion (Internet)?

8

9

ACLU and Murderers Penniless

10

The American Civil Liberty Union (ACLU) is working for a moratorium on executions

11

and to put an end to state-sanctioned murder in the United States. They claim it is very

12

disturbing to anyone who values human life.

13

In the article of the ACLU Evolution Watch, the American Bar Association said the

14

quality of the legal representation is substantial. Ninety-nine percent of criminal defendants end

15

up penniless by the time their case is up for appeal. They claim they are treated unfairly. Most

16

murderers who do not have any money, receive the death penalty. Those who live in counties

17

that are pro-death penalty are more likely to receive the death penalty (Internet).

18

19

Death Penalty Failed as a Deterrent

20

Some criminologists claim they have statistically proven that when an execution is publicized,

21

more murders occur in the day and weeks that follow. A good example is in the Linberg

22

kidnapping. A number of states adopted the death penalty for crimes like this, but figures

23

showed kidnapping increased. Publicity may encourage crime instead of preventing it

24

(McClellan, G., 1961).

25

Death is one penalty which makes error irreversible and the chance of error is inescapable

26

when based on human judgment. On the contrary, sometimes defendants insist on execution.

27

They feel it is an act of kindness to them. The argument here is - Is life imprisonment a crueler

28

fate?‖

29

citizens (McClellan, G. 1961)?

30

31

Is there evidence supporting the usefulness of the death penalty securing the life of the

Does the death penalty give increased protection against being murdered? This argument

for continuation of the death penalty is most likely a deterrent, but it has failed as a deterrent.

21

32

There is no clear evidence because empirical studies done in the 50s by Professor Thorsten

33

Sellin, (sociologist) did not give support to deterrence (McClellan, G., 1961).

34

35

36

Does not Discourage Crime

It is noted that we need extreme penalty as a deterrent to crime. This could be a strong

37

argument if it could be proved that the death penalty discourages murderers and kidnappers.

38

There is strong evidence that the death penalty does not discourage crime at all (McClellan, G.,

39

1961). Grant McClellan (1961) claims: In 1958 the10 states that had the fewest murders –fewer

40

than two a year per 100,000 population-were New Hampshire Iowa, Minnesota, Massachusetts,

41

Connecticut, Wisconsin, Rhode Island, Utah, North Dakota and Washington. Four of

42

these 10 states had abolished the death penalty.

43

44

The 10 states, which had the most murders, from eight to fourteen killings per100,000

45

population, were Nevada, Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas, and Virginia-all of them enforce the

46

death penalty. The fact is that fear of the death penalty has never served to reduce the crime rate

47

(McClellan, 1961, p. 40).

48

49

50

Conviction of the Innocent Occurs

The states that have the death penalty should be free of murder, but those states have the

51

most murders, and the states that abolished the death penalty have less. Conviction of the

52

innocent does occur and death makes a miscarriage of justice irrevocable. Two states, Maine

53

and Rhode Island, abolished the death penalty because of public shame and remorse after they

54

discovered they executed some innocent men.

55

56

57

Fear of Death Does not Reduce Crime

The fear of the death penalty has never reduced crime. Through most of history

58

executions were public and brutal. Some criminals were even crushed to death slowly under

59

heavy weight. Crime was more common at that time than it is now. Evidence shows execution

60

does not act as a deterrent to capital punishment.

61

62

22

63

64

Motives for Death Penalty-Revenge

According to Grant McClellan (1961), the motives for the death penalty may be for

65

revenge. Legal vengeance solidifies social solidarity against law breakers and is the alternative

66

to the private revenge of those who feel harmed.

23

1

A Feminist's Argument for McCain's VP from http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-

2

bin/article/article?f=/c/a/2008/09/07/INB312NP3M.DTL

3

In the shadow of the blatant and truly stunning sexism launched against the Hillary Rodham Clinton

4

presidential campaign, and as a pro-choice feminist, I wasn't the only one thrilled to hear Republican

5

John McCain announce Gov. Sarah Palin as his running mate. For the GOP, she bridges for

6

conservatives and independents what I term "the enthusiasm gap" for the ticket. For Democrats, she

7

offers something even more compelling - a chance to vote for a someone who is her own woman, and

8

who represents a party that, while we don't agree on all the issues, at least respects women enough to

9

take them seriously.

10

11

Whether we have a D, R or an "i for independent" after our names, women share a different life

12

experience from men, and we bring that difference to the choices we make and the decisions we

13

come to. Having a woman in the White House, and not as The Spouse, is a change whose time has

14

come, despite the fact that some Democratic Party leaders have decided otherwise. But with the Palin

15

nomination, maybe they'll realize it's not up to them any longer.

16

17

Clinton voters, in particular, have received a political wake-up call they never expected. Having

18

watched their candidate and their principles betrayed by the very people who are supposed to be the

19

flame-holders for equal rights and fairness, they now look across the aisle and see a woman who

20

represents everything the feminist movement claimed it stood for. Women can have a family and a

21

career. We can be whatever we choose, on our own terms. For some, that might mean shooting a

22

moose. For others, perhaps it's about shooting a movie or shooting for a career as a teacher. However

23

diverse our passions, we will vote for a system that allows us to make the choices that best suit us.

24

It's that simple.

25

26

The rank bullying of the Clinton candidacy during the primary season has the distinction of simply

27

being the first revelation of how misogynistic the party has become. The media led the assault, then

28

the Obama campaign continued it. Trailblazer Geraldine Ferraro, who was the first female

29

Democratic vice presidential candidate, was so taken aback by the attacks that she publicly decried

30

nominee Barack Obama as "terribly sexist" and openly criticized party chairman Howard Dean for

31

his remarkable silence on the obvious sexism.

32

24

33

Concerned feminists noted, among other thinly veiled sexist remarks during the campaign, Obama

34

quipping, "I understand that Sen. Clinton, periodically when she's feeling down, launches attacks as a

35

way of trying to boost her appeal," and Democratic Rep. Steve Cohen in a television interview

36

comparing Clinton to a spurned lover-turned-stalker in the film, "Fatal Attraction," noting, "Glenn

37

Close should have stayed in that tub, and Sen. Clinton has had a remarkable career...". These

38

attitudes, and more, define the tenor of the party leadership, and sent a message to the grassroots and

39

media that it was "Bros Before Hoes," to quote a popular Obama-supporter T-shirt.

40

41

The campaign's chauvinistic attitude was reflected in the even more condescending Democratic

42

National Convention. There, the Obama camp made it clear it thought a Super Special Women's

43

Night would be enough to quell the fervent support of the woman who had virtually tied him with

44

votes and was on his heels with pledged delegates.

45

46

There was a lot of pandering and lip service to women's rights, and evenings filled with anecdotes of

47

how so many have been kept from achieving their dreams, or failed to be promoted, simply because

48

they were women. Clinton's "18 million cracks in the glass ceiling" were mentioned a heck of a lot.

49

More people began to wonder, though, how many cracks does it take to break the thing?

50

Ironically, all this at an event that was negotiated and twisted at every turn in an astounding effort not

51

to promote a woman.

52

53

Virtually moments after the GOP announcement of Palin for vice president, pundits on both sides of

54

the aisle began to wonder if Clinton supporters - pro-choice women and gays to be specific - would

55

be attracted to the McCain-Palin ticket. The answer is, of course. There is a point where all of our

56

issues, including abortion rights, are made safer not only if the people we vote for agree with us - but

57

when those people and our society embrace a respect for women and promote policies that increase

58

our personal wealth, power and political influence.

59

60

Make no mistake - the Democratic Party and its nominee have created the powerhouse that is Sarah

61

Palin, and the party's increased attacks on her (and even on her daughter) reflect that panic.

62

The party has moved from taking the female vote for granted to outright contempt for women. That's

63

why Palin represents the most serious conservative threat ever to the modern liberal claim on issues

64

of cultural and social superiority. Why? Because men and women who never before would have

65

considered voting for a Republican have either decided, or are seriously considering, doing so.

25

66

They are deciding women's rights must be more than a slogan and actually belong to every woman,

67

not just the sort approved of by left-wing special interest groups.

68

Palin's candidacy brings both figurative and literal feminist change. The simple act of thinking

69

outside the liberal box, which has insisted for generations that only liberals and Democrats can be

70

trusted on issues of import to women, is the political equivalent of a nuclear explosion.

71

The idea of feminists willing to look to the right changes not only electoral politics, but will put more

72

women in power at lightning speed as we move from being taken for granted to being pursued,

73

nominated and appointed and ultimately, sworn in.

74

75

It should be no surprise that the Democratic response to the McCain-Palin ticket was to immediately

76

attack by playing the liberal trump card that keeps Democrats in line - the abortion card - where the

77

party daily tells restless feminists the other side is going to police their wombs.

78

The power of that accusation is interesting, coming from the Democrats - a group that just told the

79

world that if you have ovaries, then you don't count.

80

81

Yes, both McCain and Palin identify as anti-abortion, but neither has led a political life with that

82

belief, or their other religious principles, as their signature issue. Politicians act on their passions - the

83

passion of McCain and Palin is reform. In her time in office, Palin's focus has not been to kick the

84

gays and make abortion illegal; it has been to kick the corrupt and make wasteful spending illegal.

85

The Republicans are now making direct appeals to Clinton supporters, knowingly crafting a political

86

base that would include pro-choice voters.

87

88

On the day McCain announced her selection as his running mate, Palin thanked Clinton and Ferraro

89

for blazing her trail. A day later, Ferraro noted her shock at Palin's comment. You see, none of her

90

peers, no one, had ever publicly thanked her in the 24 years since her historic run for the White

91

House. Ferraro has since refused to divulge for whom she's voting. Many more now are realizing that

92

it does indeed take a woman - who happens to be a Republican named Sarah Palin.

26

1

Ban on a Type of Prayer in School Allowed to Stand from

2

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/politics/2008802198_apscotusprayercontroversy.html

3

WASHINGTON (AP) — Coach Marcus Borden used to bow his head and drop to one knee

4

when his football team prayed. But the Supreme Court on Monday ended the practice when it

5

refused to hear the high school coach's appeal of a school district ban on employees joining a

6

student-led prayer.The decision on the case from New Jersey could add another restriction on

7

prayer in schools, advocates said.

8

9

"We've become so politically correct in terms of how we deal with religion that it's being pretty

10

severely limited in schools right now, and individuals suffer," said John W. Whitehead, president

11

of The Rutherford Institute, a civil liberties organization that focuses on First Amendment and

12

religious freedom issues.

13

14

But Barry W. Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State,

15

said some parents had complained about Borden leading prayers before the East Brunswick, N.J.,

16

school district ordered him to stop and banned all staff members from joining in student-led

17

prayer.

18

19

"The bottom line is people in positions of authority, like a coach, have to be extremely careful

20

about trying to promote their ideas, or implying that if you don't pray, you may not play," Lynn

21

said.

22

23

The high court without comment refused to reconsider the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals'

24

decision upholding the ban. The district established the ban in 2005 after parents complained

25

about Borden, coach at East Brunswick High School since 1983, sometimes leading prayers at

26

the Friday afternoon team pasta dinner or in the locker room before games. Borden said he

27

wanted to show respect for the students engaged in prayer by bowing his head silently and

28

dropping to one knee.

29

27

30

The district, Borden argued, was violating his free-speech rights by ordering him to stop action

31

he called secular signs of respect. After the ban, the coach stood at attention for the remainder of

32

the season while the students prayed.

33

34

Judge D. Michael Fisher, writing for the Philadelphia appeals court, said Borden's past action of

35

leading the prayers made his head-bowing seem inappropriate. "A reasonable observer would

36

conclude that he is continuing to endorse religion when he bows his head during the pre-meal

37

grace and takes a knee with his team in the locker room while they pray," Fisher said.

38

39

Messages left for Borden and lawyer Ronald Riccio were not immediately returned Monday.

40

"With teachers and students, individual expressions are being limited. There's just a concept out

41

there that religion doesn't belong in schools," said Whitehead, whose group acted as co-counsel

42

for Borden. He said he does not know what Borden would do now.

43

44

School employees should avoid looking like they're endorsing religion in any way, said Lynn,

45

whose group represented the school district. "Coaches are not supposed to be promoting

46

religion; that's up to students and parents and pastors," Lynn said.

47

The Supreme Court ended school-sponsored prayer in 1962 when it said directing that a prayer

48

be said at the beginning of each school day was a violation of the First Amendment. The justices

49

reaffirmed the decision in 2000 by saying a Texas school district was giving the impression of

50

prayer sponsorship by letting students use loudspeakers under the direction of a faculty member

51

for prayers before sports events.

28

Rule Enforcement without Visible Means: Christmas Gift Giving in Middletown

Theodore Caplow

A closer look at everyday and routine events can be revealing. In this 1984 article,

Theodore Caplow analyzes the ―rules‖ that underlie gift giving in Christian homes

during Christmas in ―Middletown.‖ As Caplow makes dear, although these rules

are not anywhere published, most people seem to know to follow them

scrupulously.

Questions

1. In your judgment, why is it deemed inappropriate by Middletown families to display or

photograph unwrapped gifts?

2. Which of the rules mentioned by Caplow are followed by you and your family or (if you don‘t

celebrate the holiday) by others known to you? Which aren‘t followed?

3. Caplow suggests that people who break the rules regarding gift giving run no risk of sanction.

Do you agree? Let us say, for example, that you found shopping to be more trouble than its

worth and decided to give your parents or your partner/spouse gift certificates for generous

amounts. Would you be sanctioned in any way? How so? Likewise, suppose you violated the

―scaling rule‖ by giving every person in your family the exact same thing. What would be their

response?

4. Consider other special times when gift giving is deemed appropriate—Chanukah or birthdays,

for example. What rules govern those sorts of interaction?

The Middletown III study is a systematic replication of the well known study of a midwestern

industrial city conducted by Robert and Helen Lynd in the 1920s (Lynd and Lynd 1929/1959)

and partially replicated by them in the 1930s (Lynd and Lynd 1937/1963). The fieldwork for

Middletown III was conducted in 1976-79, its results have been reported in Middletown Families

(Caplow at al. 1982) and in 38 published papers by various authors; additional volumes and

papers are in preparation. Nearly all this material is an assessment of the social changes that

occurred between the 1920s and the 1970s in this one community, which is, so far, the only place

in the United States that provides such long-term comprehensive sociological data. The

Middletown III research focused on those aspects of social structure described by the Lynds in

order to utilize the opportunities for longitudinal comparison their data afforded, but there was

one important exception. The Lynds had given little attention to the annual cycle of religiouscivic family festivals (there were only two inconsequential references to Christmas in

Middletown and none at all to Thanksgiving or Easter), but we found this cycle too important to

ignore. The celebration of Christmas, the high point of the cycle, mobilizes almost the entire

population for several weeks, accounts for about 4% of its total annual expenditures, and takes

precedence over ordinary forms of work and leisure. In order to include this large phenomenon,

we interviewed a random sample of 110 Middletown adults early in 1979 to discover how they

and their families had celebrated Christmas in 1978. The survey included an inventory of all

Christmas gifts given and received by these respondents. Although the sample included a few

very isolated individuals, all of these had participated in Christmas giving in the previous year.

The total number of gifts inventoried was 4,347, a mean of 39.5 per respondent. The distribution

29

of this sample of gifts by type and value, by the age and sex of givers and receivers, and by giftgiving configurations has been reported elsewhere (Caplow 1982).

In this paper, I discuss a quite different problem: How are the rules that appear to govern

Christmas gift giving in Middletown communicated and enforced? There are no enforcement

agents and little indignation against violators. Nevertheless, the level of participation is very

high.

Here are some typical gift-giving rules that are enforced effectively in Middletown

without visible means of enforcement and indeed without any widespread awareness of their‘‘

existence:

The Tree Rule

Married couples with children of any age should put up Christmas

trees in their homes. Unmarried persons with no living children

should not put up Christmas trees. Unmarried parents (widowed,

divorced, or adoptive) may put up trees but are not required to do

so.

Conformity with the Tree Rule in our survey sample may be fairly described as spectacular.

Nobody in Middletown seems to be consciously aware of the norm that requires married

couples with children of any age to put up a Christmas tree, yet the obligation is so compelling

that, of the 77 respondents in this category who were at home for Christmas 1978, only one—the

Venezuelan woman—failed to do so. Few of the written laws that agents of the state attempt to

enforce endless paperwork and threats of violence are so well obeyed as this unwritten rule that

is promulgated by no identifiable authority and backed by no evident threat. Indeed, the

existence of the rule goes unnoticed. People in Middletown think that putting up a Christmas tree

is an entirely voluntary act. They .know that it has some connection with children; but they do

not understand that married couples with children of any age are effectively required to have

trees and that childless unmarried people are somehow prevented from having them. Middletown

people do not consciously perceive the Christmas tree as a symbol of the complete nuclear

family (father, mother, and one or more children). Those to whom we suggested that possibility

seemed to resent it.

The Wrapping Rule

Christmas gifts must be wrapped before they are presented.

A subsidiary rule requires that the wrapping be appropriate, that is, emblematic, and another

subsidiary rule says that wrapped gifts are appropriately displayed as a set but that unwrapped

gifts should not be so displayed. Conformity with these rules is exceedingly high.

An unwrapped object is so dearly excluded as a Christmas gift that Middletown people

who wish to give something at that season without defining it as a Christmas gift have only to

leave the object unwrapped. Difficult-to-wrap Christmas gifts, like a pony or a piano, are

wrapped symbolically by adding a ribbon or bow or card and are hidden until presentation.

In nearly every Middletown household, the wrapped presents are displayed under or

around the Christmas tree as a glittering monument to the family‘s affluence and mutual

affection. Picture taking at Christmas gatherings is clearly a part of the ritual; photographs were

taken at 65% of the recorded gatherings. In nearly all instances, the pile of wrapped gifts was

photographed; and individual participants were photographed opening a gift, ideally at the

moment of ―surprise.‖ Although the pile of wrapped gifts is almost invariably photographed, a

30

heap of unwrapped gifts is not a suitable subject for the Christmas photographer. Among the 366

gatherings we recorded, there was a single instance in which a participant, a small boy, was

photographed with all his unwrapped gifts. To display unwrapped as a set seems to invite the

insidious comparison of gifts—and of the relationships they represent.

The Decoration Rule

Any room where Christmas gifts are distributed should be

decorated by affixing Christmas emblems to the walls, the ceiling,

or the furniture.

This is done even in nondomestic places, like offices or restaurant dining rooms, if gifts are to be

distributed there. Conformity to this rule was perfect in our sample of 366 gatherings at which

gifts were distributed, although, once again, the existence of the rule was not recognized by the

people who obeyed it.

The same lack of recognition applies to the interesting subsidiary rule that a Christmas

tree should not be put up in an undecorated place, although a decorated place need not have a

tree. Unmarried, childless persons normally decorate their homes, although they have no trees,

and decorations without a tree are common in public places, but a Christmas tree in an

undecorated room would be unseemly. It goes without saying that Christmas decorations must be

temporary, installed for the season and removed afterward (with the partial exception of outdoor

wreaths, which are sometimes left to wither on the door). A room painted in red and green, or

with a frieze of plaster wreaths, would not be decorated within the meaning of the rule.

The Gathering Rule

Christmas gifts should be distributed at gatherings where every

person gives and receives gifts.

Compliance with this rule is very high. Morethan nine-tenths of the 1,378 gifts our respondents

received, and of the 2,969 they gave, were distributed in gatherings, more than three-quarters of

which were family gatherings. Most gifts mailed or shipped by friends and relatives living at a

distance were double wrapped, so that the outer unceremonious wrappings could be removed and

the inner packages could be placed with the other gifts to be opened at a gathering. IN the

typical family gathering, a number of related persons assemble by prearrangement at the home of

one of them where a feast is served; the adults engage in conversation; the children play;

someone takes photographs; gifts are distributed, opened, and admired; and the company then

disperses. The average Middletown adult fits more than three of these occasions into a 24-hour

period beginning at Christmas Eve, often driving long distances and eating several large dinners

during that time.