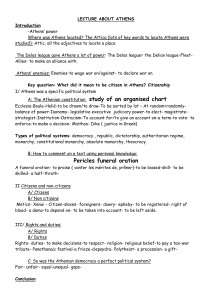

attica - Hellenismos.com

advertisement