Repurposing Former Automotive Manufacturing Sites

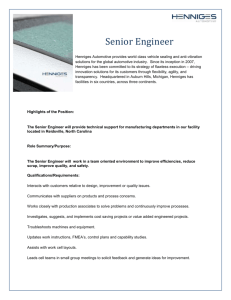

advertisement