Equipment Leasing: Analysis of Industry Practices Emphasizing

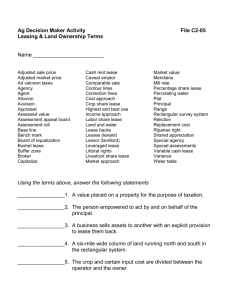

advertisement