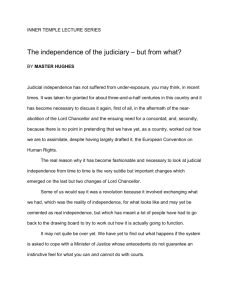

are senior judges unconstitutional?

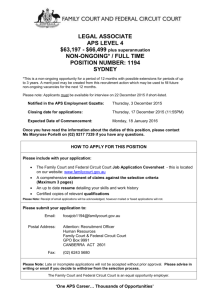

advertisement