Vol. 38 No. 1 & 2

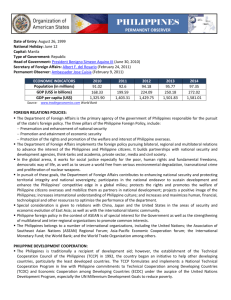

advertisement