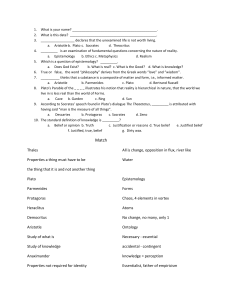

Protagoras

advertisement