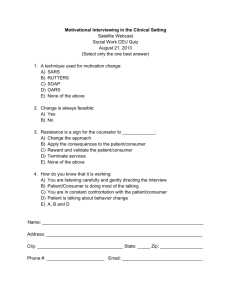

Training professionals in motivational interviewing

advertisement